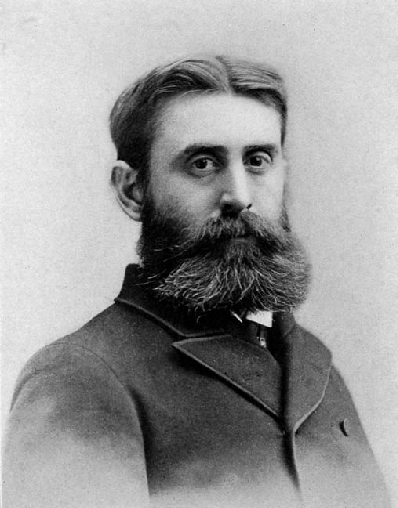

by B. B. Warfield

by B. B. Warfield

One of the most difficult questions which the seeker after souls has to meet arises out of the doctrine of Inability. The sinner, with anxious earnestness, asks the great question, “What, then, must I do to be saved?” He cannot be put off, and he ought not to be put off, with a mere “You can do nothing.” This is not the Scripture answer. The scriptures certainly do not say, as many would have us say, "Go and pray, listen to the gospel, use the sacrament and strive to live a hold life." All this is needful. But many a man may say in reply: "All this I have done from my youth up; what lack I yet? - what must I do to be saved?" The Bible answers briefly and pointedly: "Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved." But many not the sinner answer that this is precisely what he cannot do? May he not reply that, being wholly dead in sin, the exercise of faith is just what he cannot attain unto?

Such a response may doubtless be nothing more than a theoretical difficulty raised by the sinner as an excuse for not obeying the command of God. In such a case it is enough, in reply to it, to point out that at bottom it is a cavil. The command to believe is explicit. And the object of faith is most winningly presented to the mind and heart. Our obvious duty is to believe: and if we do not do so the responsibility rests upon us. That we cannot do so is the result and index of our sinfulness. Inability is a sinful condition of the will, and the sole reason why a man cannot believe is that he is so exceedingly sinful that such a one as he cannot use his will for believing. He cannot will to do it because he loves sin too much. For such a “cannot” he is certainly responsible.

But the objection is not a mere theoretical cavil, but a real practical difficulty, the expression of a soul despairingly conscious of its sin and of its sinful inability. In such a case it stands in the way of a soul seeking life, and must be dealt with in faithful gentleness.

…

1. Something may be done toward removing the difficulty by pointing out the nature of the puzzle into which the mind has fallen. The puzzle is a logical one, and concerns doctrine, not action; and it must not be permitted to stand as an obstacle to action. Regeneration is not a fact of experience, but an inference from experience; and inability is not a ground of quiescence, but an inference from quiescence. It passes away in regeneration; and no one can know that it is gone save by the change in activity. We reason back from our experience and call in the doctrine of inability to explain our actual conduct, and that of regeneration to explain the gulf between our conduct of yesterday and today. But that gulf is revealed in consciousness only by action. No man can know, then, whether he is unable save [except] by striving to act.

We may point out, therefore, that the doctrine of inability does not affirm that we cannot believe, but only that we cannot believe in our own strength. It affirms only that there is no natural strength with us by which we may attain to belief. But this is far from asserting that on making the effort we shall find it impossible to believe. We may believe, in God’s strength. Our case is parallel to that of the man with the withered hand. He knew he could not stretch it forth: that was the very characteristic of a withered hand - it was impotent. But Christ commanded, and he stretched it forth. So God command what he wills and gives while he commands. Unable in ourselves, we may taste and see that the Lord is gracious. These very struggles of the soul are an evidence of the working of the Holy Spirit within us. So that we are justified in saying to every distressed sinner, in the words of Principle God: "Act against sin, in Christ's name, as if you had strength, and you will find you have."

2. In order to incite to the requisite action was may uncover the frequent commands of God to believe and the frequent unlimited and universal promises of acceptance. We may show that man has nothing to do with God's part in the work, but only with his own; and pressing the commands and pleading the promises, excite to the effort, depending on God's promises. This very effort is already as exercise of the required faith. And thus the sinner may be led to perform the act and claim the promise.

That faithful preacher and successful evangelist, Robert Murray M'Cheyne, gives in his sermons many examples of the dealings of a true minister of Christ with sinners. He never glosses their inability. To the objection that the heart is hard and cannot believe, he replies: "This does but aggravate your guilt. It is true you were born thus, and that your heart is like the nether millstone. But that is the very reason God will most justly condemn you; because from your infancy you have been hard-hearted and unbelieving." But he make this very inability the reason why we should look from ourselves to a Savior for salvation. "You say you cannot look, nor come, nor cry, for you are helpless. He, then, and you soul shall live. Jesus is a Savior to the helpless. Christ is not only a Savior to those who are naked and empty, and have no goodness to recommend themselves, but he is a Savior to those who are unable to give themselves to him. You cannot be in too desperate a condition for Christ." He is the essence of the matter: Christ is needed as a Savior all the more because we cannot to the least thing to save ourselves.

3. To drive home the appeal we may emphasize the dangers of delay, and the roots of it in a sinful state. McCosh has a striking sermon on "Waiting for God," in which a fine example is given of this faithful appeal. "But I have a commission t proclaim," he says: "God;s reign in your hearts is pressed upon you. ... But you say you can do nothing without grace, you are waiting for it. Ah, there is a reason to fear that to all thy other sins thou art adding the sin of hypocrisy. Thou art not waiting for grace, but in thy secret heart for something very different. Determined to cherish thy self-righteousness, thou art waiting for self-indulgence, waiting for earthly goods and pleasures. God does offer thee grace, but thou wishest to remain graceless. Thou mightest be made humble, but thou art determined to remain proud. Thou mightest have they self-righteous spirit subdued, and thou art resolved to lean on thine own deeds. Thou mightest have they selfishness eradicated, but thou art resolute in pursuing thine own immediate worldly interests. Thou mightest become holy, but thou art bent on abiding unholy. Friend, I would strip you of these false pretexts by which thou art deceiving thyself, but by which thou canst not deceive God. Away with the delusion that thou hast been waiting for God, when thou hast been waiting for self-seeking ends. Let there be a surrender at once of thy self-will. Commit thyself at once and implicitly into God's hands. If thou knewest the gift of God, and how good he is to them that 'wait for him," though wouldst even now submit thyself to him and do with thee as seemeth to him good; to bend thee as thou requirest to be bent; to change thee as thou requirest to be changed; and to fashion thee anew after his own pleasure. And say not that thou art waiting for the movement of the Spirit, as the impotent man waited for the pool for the troubling of the waters. For the spiritually impotent are cured not by any wished-for movement of their spirits, but by Christ himself as he passes by; and he is now passing by and ready to heal."

This seems to me an admirable specimen of faithful dealing with such souls: they are not to be argued with but pressed to come at once to Jesus.

-----

From B.B. Warfield, Selected Shorter Writings Vol. 2

-----

Related Resources

Human Inability by C. H. Spurgeon

Responsibility, Inability and Grace (Chart) @Monergism

Inability: Free Will Vs. Free Agency by J I Packer

Man's Utter Inability to Rescue Himself, by Thomas Boston