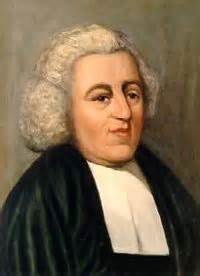

by John Newton

by John Newton

December 8, 1775.

My Dear Friend,

Are you willing that I should still call you so, or are you quite weary of me? Your silence makes me suspect the latter. However, it is my part to fulfill my promise, and then leave the event to God. As I have but an imperfect remembrance of what I have already written, I may be liable to some repetitions. I cannot stay to comment upon every line in your letter—but I proceed to notice such passages as seem most to affect the subject in debate. When you speak of the Scripture's maintaining one consistent sense, which, if it is the Word of God, it certainly must do, you say you read and understand it in this one consistent sense; nay, you cannot remember the time when you did not.

It is otherwise with me, and with multitudes; we remember when it was a sealed book; and we are sure it would have been so still, had not the Holy Spirit opened our understandings. But when you add, "Though I pretend not to understand the whole—yet what I do understand appears perfectly consistent;" I know not how far this exception may extend; for perhaps the reason why you allow you do not understand some parts, is because you cannot make them consistent with the sense you put upon other parts. You quote my words, "That when we are conscious of our depravity, reasoning stands us in no stead." Undoubtedly reason always will stand rational creatures in some stead; but my meaning is, that, when we are deeply convinced of sin, all our former reasoning upon the ways of God, while we made our conceptions the standard by which we judge what is befitting Him to do, as if He were altogether such an one as ourselves—all those cobweb reasonings are swept away, and we submit to him without reasoning, though not without reason—for we have the strongest reason imaginable to acknowledge ourselves vile and lost, without righteousness and strength, when we actually feel ourselves to be so.

You speak of the Gospel terms of justification. The term is faith, Mar. 16:16; Act. 13:39; the Gospel propounds, admits, no other term. But this faith, as I endeavored to show in my former letter, is very different from rational assent. You speak likewise of the law of faith; by which, if you mean what some call the remedial law, which we are to obey as well as we can, and such obedience, together with our faith, will entitle us to acceptance with God—I am persuaded the Scripture speaks of no such thing. Grace, and works of any kind, in the point of acceptance with God—are mentioned by the Apostle not only as opposites, or contraries—but as absolutely contradictory to each other, like fire and water, light and darkness; so that the affirmation of one—is the denial of the other; Romans 4:5, and Romans 11:6. God justifies freely, justifies the ungodly, and him who works not. Though justifying faith is indeed an active principle, it works by love; yet not for acceptance. Those whom the Apostle exhorts "to work out their own salvation with fear and trembling," he considers as justified already; for he considers them as believers, in whom he supposed God had already begun a good work; and, if so, was confident that God would accomplish it; Phi. 1:6.

To them, the consideration that God (who dwells in the hearts of believers) wrought in them to will and to do, was a powerful motive and encouragement to them to work; that is, to give all diligence in his appointed means. As a right sense of the sin that dwells in us, and the snares and temptations around us, will teach us still to work with fear and trembling.

You suppose a difference between Christians (so called) who are devoted to God in baptism, and those who in the first ages were converted from abominable superstitions and idolatrous vices. It is true, in Christian countries we do not worship Heathen divinities; and this is the principal difference I can find. Neither reason nor observation will allow me to think that human nature is a whit better now, than it was in the Apostle's time. I know no kinds or degrees of wickedness which prevailed among Heathens, which are not prevalent among nominal Christians, who have perhaps been baptized in their infancy; and therefore, as the streams in the life are equally worldly, sensual, devilish—I doubt not but the fountain in the heart is equally polluted and poisonous. It is as equally true, as in the days of Christ and his Apostles, that unless a man is born again—he cannot see the kingdom of God.

You sent me a sermon upon the new birth, or regeneration, and you have several of mine on the same subject. I wish you to compare them with each other, and with the Scripture; and I pray God to show you wherein the difference consists, and on which side the truth lies.

When you desire me to reconcile God's being the author of sin with his justice, you show that you misunderstand the whole strain of my sentiments; for I am persuaded you would not misrepresent them. It is easy to charge harsh consequences, which I neither allow, nor indeed do they follow from my sentiments. God cannot be the author of sin, in that sense you would fix upon me; but is it possible that upon your plan you find no difficulty in what the Scripture teaches us upon this subject? I conceive, that those who were concerned in the death of Christ were very great sinners, and that in nailing him to the cross they committed atrocious wickedness. Yet, if the Apostle may be believed—all this was according to the determinate counsel and foreknowledge of God, Act. 2:23; and they did no more than what His hand and purpose had determined should be done, Act. 4:28. And you will observe, that this wicked act (wicked with respect to the perpetrators) was not only permitted—but foreordained, in the strongest and most absolute sense of the word.

The glory of God and the salvation of men, depended upon its being done, and just in that manner and with all those circumstances which actually took place; and yet Judas and the rest acted freely, and the wickedness was properly their own. Now, my friend, the arguments which satisfy you that the Scripture does not represent God as the author of this sin in this appointment, will plead for me at the same time; and when you think you easily overcome me by asking, "Can God be the author of sin?" your imputation falls as directly upon the Word of God himself.

God is no more the author of sin, than the sun is the cause of ice; but it is in the nature of water to congeal into ice when the sun's influence is suspended to a certain degree. So there is sin enough in the hearts of men to make the earth the very image of hell, and to prove that men are no better than incarnate devils—were he to suspend his influence and restraint. Sometimes, and in some instances, he is pleased to suspend it considerably; and so far as he does, human nature quickly appears in its true colors.

Objections of this kind have been repeated and refitted before either you or I were born; and the Apostle evidently supposes they would be urged against his doctrine, when he obviates the question, "Why does he yet find fault? Who has resisted his will?" To which he gives no other answer than by referring it to God's sovereignty, and the power which a potter has over the clay.

I acknowledge that I am fallible; yet I must again lay claim to a certainty about the way of salvation. I am as sure of some things—as of my own existence! However, my sentiments are confirmed by the testimonies of thousands who have lived before me, of many with whom I have personally conversed in different places and circumstances, unknown to each other; yet all have received the same views—because taught by the same Spirit. And I have likewise been greatly confirmed by the testimony of many with whom I have conversed in their dying hours. I have seen them rejoicing in the prospect of death, free from fears, breathing the air of immortality; heartily disclaiming their duties and performances; acknowledging that their best actions were attended with evil sufficient to condemn them; renouncing every shadow of hope—but what they derived from the blood of Christ, as the sole cause of their acceptance; yet triumphing in him over every enemy and fear, and as sure of heaven as if they were already there!

Such were the Apostle's hopes, wholly founded on knowing whom he had believed, and his persuasion of his ability to keep that which he had committed unto him. This is faith, a renouncing of everything we are apt to call our own, and relying wholly upon the blood, righteousness, and intercession of Jesus. However, I cannot communicate this my certainty to you; I only tell you there is such a thing, in hopes, if you do not think I willfully lie both to God and man, you will be earnest to seek it from him who bestowed it on me, and who will bestow it upon all who will sincerely apply to him, and patiently wait upon him for it.

I cannot but wonder, that, while you profess to believe the depravity of human nature, you should speak of good qualities inherent in it. The Word of God describes it as evil, only evil, and that continually. "The human heart is most deceitful and desperately wicked. Who really knows how bad it is?" Jeremiah 17:9. That there are such qualities as Stoics and infidels call virtue, I allow. God has not left man destitute of such dispositions as are necessary to the peace of society; but I deny there is any spiritual goodness in them, unless it is founded in a supreme love to God, has his glory for their aim, and is produced by faith in Jesus Christ. A man may give all his goods to feed the poor, and his body to be burned in zeal for the truth, and yet be a mere nothing, a tinkling cymbal, in the sight of Him who sees not as man sees—but judges the heart. Many infidels and avowed enemies to the Grace and Gospel of Christ, have made a fair show of what the world call virtue; but Christian virtue is grace, the effect of a new nature and new life; and works thus wrought in God are as different from the faint, partial imitations of them which fallen nature is capable of producing, as a living man is different from a statue! A statue may express the features and lineaments of the person whom it represents—but there is no life!

Your comment on the seventh to the Romans, latter part, contradicts my feelings. You are either of a different make and nature from me, or else you are not rightly apprised of your own state, if you do not find the Apostle's complaints very suitable to yourself. I believe it applicable to the most holy Christian upon earth. But controversies of this kind are worn thread-bare. When you speak of the spiritual part of a natural man, it sounds to me like the living part of a dead man, or the seeing part of a blind man! Paul tells me, that the natural man (whatever his spiritual part may be) can neither receive nor discern the things of God. What the Apostle speaks of himself in Romans 7, is no more, when rightly understood, than what he affirms of all who are partakers of a spiritual life, or who are true believers, Gal. 5:17.

The carnal, natural mind—is enmity against God, not subject to the law of God, neither indeed can it be. When you subjoin, "Until it be set at liberty from the law of sin," you do not comment upon the text—but make an addition of your own, which the text will by no means bear. The carnal mind is enmity. An enemy may be reconciled; but enmity itself is incurable. This carnal mind, natural man, old man, flesh—are all equivalent expressions, and denote and include the heart of man as he is by nature. This cannot be sanctified.

All that is godly or gracious in a person—is the effect of a new creation, a supernatural principle, wrought in the heart by the Gospel of Christ, and the agency of his Spirit; and until that is effected, the highest attainments, the finest qualifications in man, however they may exalt him in his own eyes, or recommend him to the notice of his fellow-worms, are but abominations in the sight of God! Luke 16:15. The Gospel is calculated and designed—to stain the pride of human glory. It is provided, not for the wise and the self-righteous, for those who think they have good hearts and good works to plead—but for the guilty, the helpless, the wretched, for those who are ready to perish; it fills the hungry with good things—but it sends the rich empty away! See Rev. 3:17-18.

You ask, If man can do nothing without an extraordinary impulse from God—is he to sit still and careless? By no means! I am far from saying man can do nothing, though I believe he cannot open his own spiritual eyes, or give himself faith. I wish every man to abstain carefully from sinful company and sinful actions, to read the Bible, to pray to God for His heavenly teaching. For this waiting upon God, he has a moral ability; and if he perseveres thus in seeking, the promise is sure, that he shall not seek in vain. But I would not have him mistake the means for the end; think himself good because he is preserved from gross vices and follies; or trust to his religious course of duties for acceptance with God; nor be satisfied until Christ is revealed in him, formed within him, dwells in his heart by faith, and until he can say, upon good grounds, "I am crucified with Christ; nevertheless I live; yet not I—but Christ lives in me!" I need not tell you these are Scriptural expressions; I am persuaded, if they were not, they would be exploded by many as unintelligible jargon.

True faith unites the soul to Christ—and thereby gives access to God, and fills it with a peace passing understanding, a living hope, a joy unspeakable and full of glory. True faith teaches us that we are weak in ourselves—but enables us to be strong in the Lord, and in the power of his might. To those who thus believe, Christ is precious! He is their beloved; they hear and know his voice; the very sound of his name gladdens their hearts; and he manifests himself to them as he does not to the world. Thus the Scriptures speak, thus the first Christians experienced; and this is precisely the language which in our days is despised as enthusiasm and folly.

For it is now as it was then, though these things are revealed to babes, and they are as sure of them as that they see the noon-day sun—they are hidden from the wise and prudent, until the Lord makes them willing to renounce their own wisdom, and to become fools, that they may be truly wise, 1Co. 1:18-19; 1Co. 3:8; 1Co. 8:2. Attention to the education of children is an undoubted duty; and it is a mercy when it so far succeeds as to preserve them from gross wickedness; but it will not change the heart! Those who receive Christ are born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man—but of God! John 1:13.

If a man professes to love the Lord Jesus, I am willing to believe him, if he does not give me proof to the contrary; but I am sure, at the same time, no one can love him, in the Scriptural sense, who does not know the need and the worth of a Savior; in other words, who is not brought, as a ruined helpless sinner, to live upon him for wisdom, righteousness, sanctification, and redemption. Those who love him thus, will speak highly of him, and acknowledge that he is their all in all. And those who thus love him, and speak of him, will get little thanks for their pains in such a world as this: "All who live godly in Christ Jesus—must suffer persecution." The world which hated him—will hate them. And though it is possible by his grace to put to silence, in some measure, the ignorance of foolish men; and though his providence can protect his people, so that not a hair of their heads can be hurt without his permission; yet the world will show their teeth—even if they are not allowed to bite.

"You are out of your mind, Paul! Your great learning is driving you insane!" Acts 26:24. "What is this babbler trying to say?" Acts 17:18. The Apostles were accounted as foolish babblers. I need not point out to you the force of these expressions. We are no better than the Apostles; nor have we reason to expect much better treatment—so far as we walk in their steps. On the other hand, there is a way of speaking of God, and goodness, and benevolence, and morality—which the world will bear well enough. But if we preach Christ as the only way of salvation, lay open the horrid evils of the human heart, tell our hearers that they are dead in trespasses and sins, and have no better ground of hope in themselves than the vilest malefactors; if we tell the virtuous and decent, as well as the profligate, that unless they are born again, and made partakers of living faith, and count all things loss for the excellency of the knowledge of Christ—that they cannot be saved—this is the message they cannot bear! We shall be called knaves or fools, uncharitable bigots, and twenty harsh names! If you have met with no treatment like this—you should suspect whether you have yet received the right key to the doctrines of Christ; for, depend upon it—the offense of the cross is not ceased!

I am grieved and surprised that you seem to take little notice of anything in the account of my deceased friend—but his wishing himself to be a Deist, and his having play-books about him in his illness. As to the plays, they were Shakespeare's, which, as a man of taste, it is no great wonder he should sometimes look at. Your remark on the other point shows that you are not much acquainted with the exercises of the human mind under certain circumstances. I believe I observed formerly, that it was not a libertine wish. Had you known him, you would have known one of the most amiable and unblemished characters. Few were more beloved and admired for an uniform course of integrity, moderation, and benevolence; but he was discouraged. He studied the Bible; believed it in general to be the Word of God; but his wisdom, his strong turn for reasoning, stood so in his way, that he could get no solid comfort from it. He felt the vanity of the schemes proposed by many men admired in the world as teachers of divinity; and he felt the vanity likewise of his own. He was also a minister, and had a sincere design of doing good. He wished to reform the profligate, and comfort the afflicted, by his preaching; but as he was not acquainted with that one kind of preaching which God owns to the edification of the hearers, he found he could do neither. A sense of disappointments of this kind distressed him. Finding in himself none of that peace which the Scripture speaks of, and none of the influence he hoped for attending his ministry, he was led sometimes to question the truth of the Scripture.

We have a spiritual enemy always near, to press upon a mind in this despondent situation: nor am I surprised that he should then wish himself a Deist; since, if there were any hope for a sinner but by faith in the blood of Jesus, he had as much of his own goodness to depend upon, as most I have known. As for the rest, if you could see nothing admirable and wonderful in the clearness, the dignity, the spirituality of his expressions, after the Lord revealed the Gospel to him, I can only say, I am sorry for it. This I know—that some people of sense, taste, learning, and reason, and far enough from my sentiments, have been greatly struck with them.

You say a death-bed repentance is what you would be sorry to give any hope of. My dear friend, it is well for poor sinners that God's thoughts and ways are as much above men's, as the heavens are higher than the earth. We agreed to communicate our sentiments freely, and promised not to be offended with each other's freedom, if we could help it. I am afraid of offending you by a thought just now upon my mind, and yet I dare not in conscience suppress it. I must therefore venture to say, that I hope those who depend upon such a repentance as your scheme points out, will repent of their repentance itself upon their death-bed at least, if not sooner.

You and I, perhaps, would have encouraged the fair-spoken young man, who said he had kept all the commandments from his youth—and would have left the thief upon the cross to perish like a villain, as he lived. But Jesus thought differently. I do not encourage sinners to defer their repentance to their death-beds; I press the necessity of a repentance this moment! But then I take care to tell them, that repentance is the gift of God; that Jesus is exalted to bestow it; and that all their endeavors that way, unless they seek to him for grace, will be vain as washing a black-man, and transient as washing a swine—which will soon return to the mire again!

I know the evil heart will abuse the grace of God; the Apostle knew this likewise, Romans 3:8, and Romans 6:8; but this did not tempt him to suppress the glorious grace of the Gospel, the power of Jesus to save to the uttermost, and his merciful promise, that whoever comes unto him, he will never cast out. The repentance of a natural heart, proceeding wholly from fear, like that of some malefactors, who are sorry—not that they have committed robbery or murder—but that they must be hanged for it! This kind of repentance, undoubtedly, is worth nothing, whether in time of health, or in a dying hour. But that gracious change of heart, views, and dispositions, which always takes place when Jesus is made known to the soul as having died that the sinner might live, and been wounded that he might be healed; this, at whatever period God is pleased to afford and effect it by his Spirit, brings a sure and everlasting salvation with it.

Still I find I have not done: you ask my exposition of the parables of the Talents and Pounds; but at present I can write no more. I have only just time to tell you, that when I begged your acceptance of my book, Omicron, nothing was farther from my expectation than a correspondence with you. The frank and kind manner in which you wrote, presently won upon my heart. In the course of our letters, I observed an integrity and unselfishness in you, which endeared you to me still more. Since then, our debates have taken a much more interesting turn. I have considered it as a call, and an opportunity put in my hand, by the especial providence of Him who rules over all. I have embraced the occasion to lay before you simply, and rather in a way of testimony than argumentation, what (in the main) I am sure is truth. I have done enough to discharge my conscience—but shall never think I do enough to answer the affection I bear you. I have done enough likewise to make you weary of my correspondence, unless it should please God to fix the subject deeply upon your mind, and make you attentive to the possibility and vast importance of a mistake in matters of everlasting concernment.

I pray that the Spirit of God may guide you into all truth. He only is the effectual teacher. I still retain a cheerful hope, that some things you can not at present receive—will be hereafter the joy and comfort of your heart: but I know it cannot be—until the Lord's own time. I cannot promise to give such long answers as your letters require, to clear up every text that may be proposed, and to answer every objection that may be started; yet I shall be glad to exchange a letter now and then. At present it remains with you, whether our correspondence continues or not, as this is the third letter I have written since I heard from you, and therefore must be the last until I do. I would think what remains might be better settled in person; for which purpose I shall be glad to see you, or ready to wait on you when leisure will permit, and when I know it will be agreeable. But if (as life and all its affairs are precarious) we should never meet in this world, I pray God we may meet at the right hand of Jesus, in the great day, when he shall come to gather up his jewels, and to judge the world! T