by Michael J. Kruger

by Michael J. Kruger

This is chapter 3 of the book Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books Copyright © 2012 by Michael J. Kruger. Posted with permisssion.

He swore by himself. - HEBREWS 6:13

The prior chapters have attempted to offer a taxonomy of canonical models, along with some reflection and critique (as difficult as that is in so little space). Throughout this analysis it has become clear that these models vary from one another in many different ways—for example, date of the New Testament, definition of canon, doctrine of Scripture, role of the church, and more. In the midst of such diversity, however, it has also become clear that all these models share one core characteristic. They all ground the authority of the canon in something outside the canon itself. It is this appeal to an external authority that unites all of these positions. As we have already noted, the insistence that the canon can be authenticated only by some external authority raises a host of theological and biblical questions. Richard Gaffin notes that such an approach is in danger of “subjecting the canon to the relativity of historical study and our fallible human insight. That is, it would destroy the New Testament as canon, as absolute authority.”1 Ridderbos also expresses concern about such approaches. He notes that “problems arise whenever the Scriptures are no longer regarded as the exclusive principle of canonicity, when something else is substituted.”2 For these models, “the final decision as to what the church deems to be holy and unimpeachable does not reside in the canon itself. Human judgment . . . is the final court of appeal.”3

What is needed, then, is a canonical model that does not ground the New Testament canon in an external authority, but seeks to ground the canon in the only place it could be grounded, its own authority. After all, if the canon bears the very authority of God, to what other standard could it appeal to justify itself? Even when God swore oaths, “he swore by himself” (Heb. 6:13). Thus, for the canon to be the canon, it must be self-authenticating. A self-authenticating model of canon would take into account something that the other models have largely overlooked: the content of the canon itself. Rather than looking only to its reception (community determined), or only to its origins (historically determined), this model would, in a sense, let the canon have a voice in its own authentication. But this raises a number of questions. What exactly do we mean when we say that the canon is self-authenticating? And does a self-authenticating canon mean that we cannot use external data?

It is the purpose of this chapter to lay forth a canonical model that addresses these questions. An overview of the model will be offered here and the full details of the model will be developed throughout the remaining chapters of the book.

I. The Concept of a Self-Authenticating Canon

The idea of a self-authenticating canon is certainly not new. The hallmark teaching of the Reformers—and the foundation for the doctrine of sola scriptura—is the self-authenticating (autopistic) nature of the canon.4 John Calvin notes, “God alone is a fit witness of himself in his Word. . . . Scripture is indeed self-authenticated.”5 Francis Turretin agrees: “Thus Scripture, which is the first principle in the supernatural order, is known by itself and has no need of arguments derived from without to prove and make itself known to us.”6 Herman Bavinck reminds us that the church fathers understood Scripture this way: “In the church fathers and the scholastics . . . [Scripture] rested in itself, was trustworthy in and of itself (αὐατοπιστος), and the primary norm for church and theology.”7 Therefore, Bavinck argues, an ultimate authority like Scripture (what he calls a “first principle”) must be “believed on its own account, not on account of something else.”8 He says elsewhere, “Scripture’s authority with respect to itself depends on Scripture.”9

But what exactly do we mean when we say that the canon authenticates itself? Upon first glance, a self-authenticating canon may seem to refer to the fact that the canon claims to be the Word of God (e.g., 2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:21; Rev. 22:18–19), implying that all we can do is accept or reject that claim.10 Although Scripture’s testimony about itself is an important aspect of biblical authority (and will be discussed more below), we will not be arguing that the canon is authenticated simply by virtue of the fact that it says so. That is not how the phrase will be used here. Others may hear the phrase “self-authenticating” and recognize it as a reference to the traditional Reformed view that the books of Scripture bear evidence in themselves of their own divinity. As a result, some may assume that a self-authenticating canon means that our model will be concerned only with the internal qualities of these books and that external data or evidence plays no role in the authentication process. While we certainly agree that these books do bear internal marks of their divinity (indeed, this will be a core component of the model put forth below), this does not mean that outside information has no place in how the canon is authenticated. We shall argue that when it comes to the question of canon, the Scriptures themselves provide grounds for considering external data: the apostolicity of books, the testimony of the church, and so forth. Of course, this external evidence is not to be used as an independent and neutral “test” to determine what counts as canonical; rather it should always be seen as something warranted by Scripture and interpreted by Scripture.

Thus, for the purposes of this study, we shall be using the phrase self-authenticating in a broader fashion than was typical for the Reformers.11 We are not using it to refer only to the fact that canonical books bear divine qualities (although they do), but are using it to refer to the way the canon itself provides the necessary direction and guidance about how it is to be authenticated. In essence, to say that the canon is self-authenticating is simply to recognize that one cannot authenticate the canon without appealing to the canon. It sets the terms for its own validation and investigation. A self-authenticating canon is not just a canon that claims to have authority, nor is it simply a canon that bears internal evidence of authority, but one that guides and determines how that authority is to be established.

Of course, for some who are used to a more foundationalist epistemology, the idea of a self-authenticating canon of Scripture might seem a bit strange.12 We tend to think that we are not justified in holding a belief unless it can be authenticated on the basis of other beliefs. But as we have already noted, this approach overlooks the unique nature of the canon. The canon, as God’s Word, is not just true, but the criterion of truth. It is an ultimate authority. So, how do we offer an account of how we know that an ultimate authority is, in fact, the ultimate authority? If we try to validate an ultimate authority by appealing to some other authority, then we have just shown that it is not really the ultimate authority. Thus, for ultimate authorities to be ultimate authorities, they have to be the standard for their own authentication. You cannot account for them without using them.

Although this whole line of thought can sound a bit circular to some, that is inevitable given the nature of the question being asked. We must remember that we are not asking simply how a person (for the first time) comes to believe that the Scripture is true—that can happen in a number of different ways, and a person may not even consciously recognize the epistemological process that allows him to acquire such knowledge.13 Nor, as we discussed in the introduction, are we attempting to somehow “prove” to the skeptic (in a way that would satisfy him) that these books are indeed from God. Rather, the question before us is whether the Christian faith, with its twenty-seven-book New Testament, can give an adequate account for how it can be known that these books are canonical. Do Christians, as the de jure objection contends, lack sufficient grounds for thinking that they can know which books belong in the canon and which do not? The question is not about our having knowledge of canon, but accounting for our knowledge of canon.14 But that question can only be answered on the basis of the Christian faith itself, that is, what Christianity actually teaches about God, the Scriptures, the nature of Christian knowledge, and so on. After all, how can the Christian account of knowledge be explained and defended without appealing to the Christian account of knowledge?

William Alston agrees that a certain degree of circularity is required in our justification of our knowledge of Scripture.

If we want to know whether, as the Christian tradition would have it, God guarantees the Bible . . . as a source for fundamental religious beliefs, what recourse is there except to what we know about God, His nature, purposes, plans and actions. And where do we go for this knowledge? In the absence of any promising suggestions to the contrary, we have to go to the very sources of belief credentials which are under scrutiny.15

This sort of circularity is not a problem but simply part of how foundational authorities are authenticated. For instance, let us imagine that we want to determine whether sense perception is a reliable source of belief. If I see a cup on the table, how do I know my sense perception is accurate? How would I test such a thing? I could examine the cup and table more closely to make sure they are what they seem to be (hold them, touch them, etc.). I could also ask a friend to tell me whether he sees a cup on the table. But in all these instances I am still assuming the reliability of my sense perception (or my friend’s) even as I examine the reliability of my sense perception. Or, as another example, let us imagine that we wanted to inquire into whether our rational faculties would reliably produce true beliefs. How could we examine the evidence for the reliability of our rational faculties without, at the same time, actually using our rational faculties (and thereby presupposing their reliability)? Alston sums it up, “There is no escape from epistemic circularity in the assessment of our fundamental sources of belief.”16

If so, then when it comes to authenticating the canon, we are not so much proving Scripture as we are using Scripture. Or, even better, we are applying Scripture to the question of which books belong in the New Testament. Perhaps this is a more tangible way to think of a self-authenticating canon because it is not all that different (in principle) from the way we apply the teaching of Scripture to any other question before us, whether politics, science, the arts, or anything else. And whenever the Scripture is applied to an issue, it is perfectly appropriate (and necessary) to use extrabiblical “facts.” For example, if we want to apply the teachings of Scripture to, say, the field of bioethics (stem-cell research, human cloning, etc.), then we cannot just read the Bible only; the Bible does not speak directly of these things. It does not tell us what cloning is and what it entails. We actually have to acquire some outside information about these bioethical issues before we can reach biblical conclusions about them. So it is when it comes to applying the Scriptures to the question of canon.

But just because our conclusions required extrabiblical data does not mean the conclusions themselves are unbiblical or uncertain. We can still have biblical knowledge even with extrabiblical data. John Frame argues at length that a sharp distinction should not be made between the meaning of the Bible and the application of the Bible—we do not really understand the meaning until we can apply it correctly to the world around us.17 Thus, he declares, “applications of Scripture are as authoritative as the specific statements of Scripture. . . . Jesus and others held their hearers responsible if they failed to apply Scripture properly.”18 The Westminster Confession affirms a similar idea when it says that authority belongs not only to those teachings “expressly set down in Scripture” but also to that which “by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture” (1.6). Similarly, even though the Scripture does not directly tell us which books belong in the New Testament canon (i.e., there is no inspired “table of contents”), we can account for that knowledge if we apply Scripture to the question. Again, where else would we turn to understand the Christian basis for receiving these books?

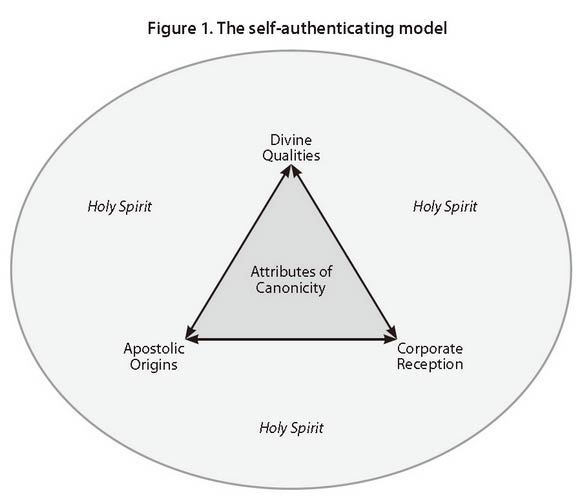

When we do apply the Scripture to the question of which books belong in the canon, we shall see that it testifies to the fact that God has created the proper epistemic environment wherein belief in the New Testament canon can be reliably formed. This epistemic environment includes three components:

Providential exposure. In order for the church to be able to recognize the books of the canon, it must first be providentially exposed to these books. The church cannot recognize a book that it does not have.

Attributes of canonicity. These attributes are basically characteristics that distinguish canonical books from all other books. There are three attributes of canonicity: (1) divine qualities (canonical books bear the “marks” of divinity), (2) corporate reception (canonical books are recognized by the church as a whole), and (3) apostolic origins (canonical books are the result of the redemptive-historical activity of the apostles).

Internal testimony of the Holy Spirit. In order for believers to rightly recognize these attributes of canonicity, the Holy Spirit works to overcome the noetic effects of sin and produces belief that these books are from God.

These three components must all be in place if we are to have knowledge of the canon. We cannot know canonical books unless we have access to those books (providential exposure); we need some way to distinguish canonical books from other books (attributes of canonicity); and we need to have some basis for thinking we can rightly identify these attributes (internal work of the Spirit). We now turn our attention to these components.

II. The Components of a Self-Authenticating Canon

A. Providential Exposure

If the covenant community is to rightly recognize God’s covenant books, it will need more than just attributes of canonicity and the work of the Holy Spirit. In addition, the covenant community will need to be collectively exposed to the canonical books. To state the obvious, the church cannot respond (positively or negatively) to a book of which it has no knowledge.19 Christ’s promise that his sheep will respond to his voice pertains only to books that have had their voice actually heard by the sheep (John 10:27). If God intended to give a canon to his corporate church—and not just to an isolated congregation for a limited period of time—then we have every reason to believe that he would providentially preserve these books and expose them to the church so that, through the Holy Spirit, it can rightly recognize them as canonical. As Evans has argued, the fact that certain books are lost “provides reason to think that God did not desire those writings to be included in the authorized revelation.”20

The inclusion of the “providential exposure” component in the self-authenticating model is not only obvious (how could the church recognize books it was not familiar with?), but also critical if we are to claim that the Christian’s epistemic environment is able to lead reliably to a knowledge of the canon. If God did not bring about the condition of corporate exposure to the church, then we would have no basis for thinking that the complete canon could actually be known. There could always be an unknown number of books left out of the canon—not because the church rejected them, but because they were lost before they could even be evaluated. Fortunately, we have good biblical grounds for affirming God’s intent in giving his Word to his church (Rom. 15:4; 2 Tim. 3:16–17) and God’s sovereign ability to accomplish it (Ps. 135:6; Dan. 4:35; Acts 17:25–28; Eph. 1:11; Heb. 1:3).

If so, then this has implications for how we are to think of books that the apostles may have written that were not preserved—such as Paul’s other letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 5:9).21 No doubt such letters, if written in an apostle’s authoritative role, would have been inspired by the Holy Spirit. But since God did not providentially allow these books to be exposed to the corporate church (apparently they were known only to a limited group and then lost or forgotten), then we have no reason to think that they are relevant for our discussion about which books are canonical. Again, how can we recognize a book’s canonicity unless we actually have that book? If the authentication of the canon is inherently about which books the church should accept or reject (and it is), then lost books, by definition, can play no role. Therefore, the self-authenticating model we are putting forth here can only be used to evaluate books that God has allowed the collective church to be exposed to, such as 1 Peter, the Shepherd of Hermas, 1 Clement, and the Gospel of John.

Of course, there is still the complex question of what terminology is appropriate for these “lost” apostolic books. What shall we call them? Although we certainly could use the term canon to refer to these books (at least in regard to the functional definition), that seems only to confuse matters. If God providentially intended some apostolic books to serve as permanent foundational books for the corporate church (e.g., John’s Gospel), and other apostolic books to serve a temporary, one-time purpose after which they were lost or forgotten (e.g., Paul’s other letter to the Corinthians), then our terminology ought to reflect such a distinction.22 If so, then it seems best to refer to these lost apostolic writings as “inspired books” or perhaps even as “Scripture.” In regard to the latter term, this would be the one instance, contra Sundberg, where there is a legitimate distinction between Scripture and canon.23 But this distinction is only applicable to the narrow foundational and redemptive-historical period of the apostles and driven by their God-given function as caretakers and founders of the church. During this unique apostolic phase, canonicity was a subset of Scripture—all canonical books were Scripture, but not necessarily all scriptural books were canonical.24

Given this distinction, the term canon may be used for books before they are corporately recognized (e.g., John ten minutes after it was written), but not for books that were never corporately recognized (e.g., lost letters of Paul).25 Such terminological distinctions, of course, are inevitably retrospective in nature. John was really canon when the ink was still wet on the autograph, but the church would have realized this only at a later point, after being exposed to John and recognizing it as canonical. The church could then look back, as we do, and realize that a canon really did exist in the first century even though at the time the church was not yet fully aware of it. Likewise, Paul’s other Corinthian letter was not canon in the first century, but this would not have been known at the time by the limited groups acquainted with it. Only later, when it was lost or forgotten, would it become clear that it was not canonical.

Therefore, canonical books, as we have defined them here, cannot be lost. If they are lost, then they were never canonical books to begin with. So, even if we were to discover Paul’s lost letter in the desert sands today, we would not place it into the canon as the twenty-eighth book. Instead, we would simply recognize that God had not preserved this book to be a permanent foundation for the church. Putting such a letter into the canon now would not change that fact; it could not make a book foundational that clearly never was.26

B. Attributes of Canonicity and the Holy Spirit

The above discussion has laid the appropriate groundwork for our canonical model. It is now clear that we are only dealing with (and can only deal with) the books we have available to us. And in this regard, we trust in the providence of God that the books available to us are the ones he intended. But, of course, this is just the very first step. Next, we must distinguish among these books available to us. How do we know which are canonical? The answer lies in the attributes of canonicity and the role of the Holy Spirit, to which we now turn.

1. Divine Qualities

Because the canonical books were constituted by the revelatory activity of the Holy Spirit, we would expect that there would be some evidence of that activity in the books themselves—the “imprint” of the Spirit, if you will. Thus, the first attribute of the canon’s self-authenticating nature is that it bears the divine qualities or divine character of a book from God.27 John Murray reasons, “If . . . Scripture is divine in its origin, character, and authority, it must bear the marks or evidences of that divinity.”28 These “marks” (or indicia) can include a variety of things, but traditionally include the Scripture’s beauty, efficacy, and harmony (which we will discuss further in a later chapter).29 Calvin himself understood that there were objective qualities evident within the canonical books that show they are from God: “It is easy to see that the Sacred Scriptures, which so far surpass all gifts and graces of human endeavor, breathe something divine.”30 Elsewhere he states, “Indeed, Scripture exhibits fully as clear evidence of its own truth as white and black things do of their color, or sweet and bitter things do of their taste.”31 And again, Calvin reaffirms the internal divine qualities of Scripture.

As far as Sacred Scripture is concerned . . . it is clearly crammed with thoughts that could not be humanly conceived. Let each of the prophets be looked into: none will be found who does not far exceed human measure. Consequently, those for whom prophetic doctrine is tasteless ought to be thought of lacking taste buds.32

As the Westminster Confession of Faith notes, these divine qualities are considered to be objective means “whereby [Scripture] doth abundantly evidence itself to be the Word of God.”33 Thus, all books that are canonical will bear these divine qualities.

In many ways the divine qualities of Scripture are analogous to the way the natural world attests to God as Creator. Christians have historically argued that we know the natural world is from God because it bears his “marks” and his “imprints.” The beauty, excellency, and harmony of creation testify to the fact that God is its author. As Psalm 19:1 states,

The heavens declare the glory of God,

and the sky above proclaims his handiwork.

And, similarly, Romans 1:20 explains, “For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.” If the created world (general revelation) is able to speak clearly that it is from God, then how much more so would the canon of Scripture (special revelation) speak clearly that it is from God? Murray draws this same connection: “If the heavens declare the glory of God and therefore bear witness to their divine creator, the Scripture as God’s handiwork must also bear the imprints of his authorship.”34

It is here that we see clearly how the doctrine of Scripture shapes one’s canonical model. The method by which the canon is authenticated is correlative with the nature of the canon being authenticated. The two must be consistent with one another. Because a number of models deny that the canon bears such inherent divine qualities—historical-critical, canonical criticism, existential/neoorthodox, and canon-within-the-canon models—then they must appeal to criteria outside the canon in order to authenticate it. On these models, the canon is not able to authenticate itself, so it has to be justified on other grounds (experience, historical evidence, etc.). Thus, once again, we see that canonical models do not (and cannot) approach the question of canon with theological neutrality. All models have prior theological convictions about what Scripture is (or is not), and this in turn determines the manner in which canon is authenticated. But where do these prior theological convictions about Scripture come from if not from Scripture itself? Ironically, then, each model must know what Scripture is before determining how it is to be authenticated. There cannot be a theologically neutral approach to canon.

Of course, once we start talking about these divine qualities contained in the canonical books, we must also discuss the means God has provided that allows them to be reliably recognized. After all, if these marks are really there in the canonical books, then how is it that so many people do not receive them or acknowledge them? If they are objectively present, why do so many reject the Bible? The answer is that, because of the noetic effects of sin, the effects of sin on the mind (Rom. 3:10–18), one cannot recognize these marks without the testimonium spiritus sancti internum, the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit.35 The Holy Spirit not only is operative within the canonical books themselves (providing the “marks” of divinity noted above), but also must be operative within those who receive them. The testimonium is not a private revelation of the Spirit or new information given to the believer—as if the list of canonical books were whispered in our ears—but it is a work of the Spirit that overcomes the noetic effects of sin and produces the belief that the Scriptures are the word of God.36 The reason some refuse to believe the Scriptures is not that there is any defect or lack of evidence in the Scriptures (the indicia are clear and objective) but that those without the Spirit do not accept the things from God (1 Cor. 2:10–14).

Jesus himself affirmed this reality when he declared, “My sheep [i.e., those with the Spirit] hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me” (John 10:27). Likewise, he said of his sheep, “A stranger they will not follow, but they will flee from him, for they do not know the voice of strangers” (John 10:5). Put simply, canonical books are received by those who have the Holy Spirit in them. When people’s eyes are opened, they are struck by the divine qualities of Scripture—its beauty, harmony, efficacy—and recognize and embrace Scripture for what it is, the word of God. They realize that the voice of Scripture is the voice of the Shepherd.37

It is here that we see both similarities and differences with a number of the community-determined models above. The self-authenticating model is similar to these models in that they all recognize a legitimate place for the subjective response of Christians in the authentication of the canon. The difference, however, is that the community-determined models make the subjective response foundational to the canon’s authority and, in some instances, that which constitutes the canonical authority. For example, in the existential/neoorthodox model the Scripture does not bear divine qualities in and of itself, but functions as the Word of God only when the Spirit decides to use it. In this sense, the authority of Scripture is utterly contingent on the subjective experience of those who receive it. The Spirit becomes the grounds of the canon’s authority, not the means to recognizing it.38 In contrast, the self-authenticating model understands the testimonium not as something that stands by itself, but as something that always stands in conjunction with the objective qualities of Scripture noted above.39 The two always go together. Indeed, they are two aspects of the same phenomenon, not to be unduly separated.40 Bavinck notes, “Scripture and the testimony of the Holy Spirit relate to each other as objective truth and subjective assurance . . . as the light and the human eye.”41 Thus, when a Christian embraces the Scriptures as the word of God, his actions are fully rational and warranted because they rest on the most sure basis possible—the divine attributes of Scripture.42 So, while there is a subjective aspect to the self-authenticating model, it is not subjectivism.43

Of course, some may still object: “But how do I know I am experiencing the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit? How do I know it isn’t, say, heartburn?” The problem with this objection is that it assumes we can only know that the Scriptures are from God if we can properly identify the testimonium. But this would be true only if the testimonium were itself the grounds for our belief—as if we argued to ourselves, “Because I am having this experience of the Spirit, therefore, on that basis, the Scripture is true.” But as we have maintained, the ground for our belief is the apprehension of the divine qualities of Scripture itself, not the testimonium or our experience with it.44 Thus, we need not be consciously aware of the work of the Spirit for the Spirit to be, in fact, working.45 It seems, then, that our belief in the truth of Scripture via the work of the Spirit is best construed not as an inductive inference from some aspect of our experience (whether the Spirit or something else),46 but, as Jonathan Edwards noted, as a more “immediate” or “intuitive” belief.47

2. Corporate Reception

In all of this discussion, we would be mistaken to think of the recognition of the canon as happening only on a personal and individualistic level (which is perhaps partly why it has seemed subjective to some).48 There are good biblical reasons to think that the testimonium would also result in a corporate, or covenantal, reception of God’s Word. By this we mean not that the church would have absolute unity regarding the canon—there would still be portions or subgroups with differing opinions—but that the church as a whole, both in the present and throughout the ages, would experience predominant unity.49 If so, then we have biblical grounds for thinking that the consensus of the church is a reliable indicator of which books are canonical.

Several considerations suggest that we should expect the canon to be received on a corporate-covenantal level. First, God’s redemptive pattern has not been simply to redeem individuals, but to redeem a people, a church, for himself (Acts 15:14; Titus 2:14; 1 Pet. 2:9). And when God, by his redemptive activity, creates a covenant community, he then gives them covenant documents that testify to that redemption.50 For these reasons, Meredith Kline and others have argued that canonical books are ultimately, and primarily, covenantal books. The biblical witness indicates that it is God’s corporate people—not as individuals but as a covenant whole—who are “entrusted with the oracles of God” (Rom. 3:2). As Kline has argued, God gives the covenant documents with the intent that those documents become a “community rule.”51 The implications of this are clear: if God’s canonical books ultimately have a corporate purpose, then we have every reason to think that the testimonium ultimately has a corporate purpose. The canon cannot rule a community unless it is received by that community. Evans argues for precisely this biblical logic.

It seems highly plausible, then, that if God is going to see that an authorized revelation is given, he will also see that this revelation is recognized. . . . On this view, then, the fact that the church recognized the books of the New Testament as canonical is itself a powerful reason to believe that these books are indeed the revelation God intended humans to have.52

Second, if we affirm the efficacy of the testimonium on an individual level, why should we be less willing to affirm its efficacy on the corporate-covenantal level? If the testimonium can reliably lead an individual to belief in the canon, there seems little reason why we should not affirm such reliability for the church as a whole. On the contrary, one might even argue that there are biblical reasons to be more confident in the role of the testimonium on a corporate level. After all, we have additional biblical testimony that we should heed “an abundance of counselors” (Prov. 11:14) and run the same path as the “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb. 12:1) that have gone before us. Moreover, it is the church, and not just the individual, that is given the Spirit: the church is God’s house (1 Tim. 3:15), also called a “spiritual house” (1 Pet. 2:5), and is a body with one Spirit (1 Cor. 12:13). All of this suggests that if we doubt the testimonium on a corporate level, we would be compelled to doubt it equally on an individual level.

Third, the covenantal-corporate aspect of the testimonium has been historically affirmed by Reformed scholars. Bavinck declares,

Subsumed under this heading of the testimony of the Holy Spirit is the witness the Spirit has borne to Scripture in the church throughout the centuries; and this witness is . . . directly [embodied] in the united confession of the believing community throughout the centuries that the Scripture is the word of God.53

Likewise, Abraham Kuyper argues that the testimony of the Holy Spirit ultimately works corporately and thereby creates a “communion of consciousness not merely with those round about us, but also with the generation of saints from former ages . . . [through which] the positive conviction prevails, that we have a graphically inspired Scripture.”54 Roger Nicole contends that we can know which books belong in the canon by appealing to “the witness of the Holy Spirit given corporately to God’s people and made manifest by a nearly unanimous acceptance of the NT canon in the Christian churches.”55 Ned Stonehouse makes a similar connection.

Although the church lacks infallibility, its confession with regard to the Scriptures, represents not mere opinion but an evaluation which is valid as derived from, and corresponding with, the testimony of the Scriptures to their own character. The basic fact of canonicity remains, then, the testimony which the Scriptures bear to their own authority. But the historian of the canon must recognize the further fact that the intrinsic authority established itself in the history of the church through the government of its divine head.56

It is here that we begin to see the proper role of the church in the authentication of canon. The books received by the church inform our understanding of which books are canonical not because the church is infallible or because it created or constituted the canon, but because the church’s reception of these books is a natural and inevitable outworking of the self-authenticating nature of Scripture. Viewing the role of the church in the context of a self-authenticating Bible can bring fresh understanding to the complex church-canon relationship and may serve as a corrective to some extreme positions in the other canonical models. The Catholic model insists that the church’s reception of these books is the sole grounds for the canon’s authority. In the self-authenticating model, however, the church’s reception of these books proves not to be evidence of the church’s authority to create the canon, but evidence of the opposite, namely, the authority, power, and impact of the self-authenticating Scriptures to elicit a corporate response from the church. Jesus’s statement that “my sheep hear my voice . . . and they follow me” (John 10:27) is not evidence for the authority of the sheep’s decision to follow, but evidence for the authority and efficacy of the Shepherd’s voice to call.57 After all, the act of hearing is, by definition, derivative not constitutive.58 Thus, when the canon is understood as self-authenticating, it is clear that the church did not choose the canon, but the canon, in a sense, chose itself.59 As Childs has noted, the content of these writings “exerted an authoritative coercion on those receiving their word.”60 Barth agrees: “The Bible constitutes itself the Canon. It is the Canon because it imposed itself upon the Church.”61 In this way, then, the role of the church is like a thermometer, not a thermostat. Both instruments provide information about the temperature in the room—but one determines it and one reflects it.

On the other extreme, some approaches have been so intent on avoiding the mistakes of Roman Catholicism that they have virtually ignored the role of the church altogether, creating a just-me-and-God type of individualism where canon is determined entirely outside any ecclesiastical or corporate considerations.62 As Kline observed, “Traditional formulations of the canon doctrine have not done full justice to the role of the community.”63 For example, Charles Briggs, while affirming the church’s role at some points, still viewed the internal testimony of the Holy Spirit so individualistically that he could declare that every man should “make up his own mind,” and the canon is a “question between every man and his God.”64 Although such an approach is often practiced under the heading of sola scriptura, it is ironic that the Scriptures themselves provide no basis for a purely “private” approach to the canon but, as noted above, consistently view the books of the canon as a covenantal (and therefore corporate) reality. Bavinck corrects this type of individualism, “The testimony of the Holy Spirit is not a private opinion but the witness of the church of all ages, of Christianity as a whole.”65

In many ways, the fact that the corporate church, as a whole, would naturally recognize the canonical books is analogous to the way justification naturally leads to good works. Just because we believe that justification inevitably produces good works in an individual does not mean Christians live a perfect life. You can imagine someone objecting to the relationship between justification and good works on the grounds that they know many Christians who commit heinous sins. However, the belief that good works follow justification does not rule out such sins, or even periods of backsliding, but is merely a claim that, through the work of the Spirit, the overall, collective direction of one’s life is one that bears fruit. Likewise, the biblical teaching that Christ’s sheep hear his voice does not require perfect reception by the church with no periods of disagreement or confusion, but simply a church that, by the work of the Holy Spirit, will collectively and corporately respond. But the analogy goes even further. The belief that justification inevitably leads to good works does not imply that good works are the grounds of, or the cause of, justification—that would be a grand misunderstanding of the doctrine. Likewise, simply because the church, through the internal witness of the Spirit, will collectively respond to the voice of Christ in these books does not make the voice of Christ in these books somehow dependent on the church. Books are not canonical because they are recognized; they are recognized because they are already canonical. It is this critical distinction that sets the self-authenticating model apart from many of the community-determined models discussed above.66

Thus, we have every biblical reason to believe that the Spirit’s work within the hearts of his people (both individually and corporately) is effectual and that Christ makes good on his promise that “my sheep hear my voice . . . and they follow me” (John 10:27). Ridderbos sums it up: “Christ will establish and build His church by causing the church to accept just this canon and, by means of the assistance and witness of the Holy Spirit, to recognize it as his.”67 Again, this does not mean that we should expect to find perfect unity among the church, but it does mean that we should expect to find a corporate or covenantal unity—which is precisely what we do find.68

3. Apostolic Origins

So far, we have seen that canonical books are characterized by two attributes: they bear the marks of divinity (divine qualities) and are recognized by the church as a whole (corporate reception). But when we read the Scriptures, there is more to the concept of canon than just these two attributes. Indeed, if only these two attributes were considered, one might erroneously get the impression that canonical books are abstract revelation from God, utterly ahistorical and timeless—something quasi-gnostic that just drops down from heaven to be given again and again throughout the life of the church. But the Scriptures do not present the canon as abstract revelation, but as redemptive revelation.69 Canonical books derive from particular redemptive epochs where God has acted in history to deliver his people. This redemptive-historical aspect of the canon is clearly visible in the fact that the two main covenants of Scripture—the old (Sinaitic) covenant and the new covenant—both are established in written form after God’s special (and powerful) redemptive work was accomplished (e.g., Ex. 20:2; John 20:31).

In regard to the establishment of the new covenant, the message of redemption in Jesus Christ was entrusted to the apostles of Christ, to whom he gave his full authority and power: “The one who hears you hears me, and the one who rejects you rejects me” (Luke 10:16). The apostles are the link between the redemptive events themselves and the subsequent announcement of those events.70 Not only did the apostles themselves write many of these New Testament documents, but, in a broader sense, they presided over the transmission of the apostolic deposit and labored to make sure that the message of Christ was firmly and accurately preserved for future generations, through the help of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:1–4; Rom. 6:17; 1 Cor. 11:23; 15:3; Gal. 1:9; Phil. 4:9; Col. 2:6–8; 1 Thess. 2:13–15; 1 Tim. 6:20; 2 Tim. 1:14; 2 Pet. 2:21; Jude 1:3). Thus, the New Testament canon is not so much a collection of writings by apostles, but a collection of apostolic writings—writings that bear the authoritative message of the apostles and derive from the foundational apostolic era (even if not directly from their hands).71 As John Webster puts it,

Canonization is recognition of apostolicity, not simply in the sense of the recognition that certain texts are of apostolic authorship or provenance, but, more deeply, in the sense of the confession that these texts [are] “grounded in the salvific act of God in Christ which has taken place once and for all.”72

Thus, we come to the third attribute of canonicity, namely, that all canonical books are apostolic books. This attribute reminds us that the authentication of canon has a strong retrospective component; it is to look backward to a particular historical epoch in which God has acted in Jesus Christ and to recognize that these books provide the authoritative apostolic interpretation of those actions.73 But it is more than that. It is not just the claim that these books are about Christ’s redemptive work in history, but it is the claim that these books are the product of Christ’s redemptive work in history—that they are the outworking of the authority Christ gave to his apostles to lay down the permanent foundation for the church.74 This is why canonical books are not only marked by divine qualities and corporate reception. They are not just instances of generic revelation that God offers the church in the present and might continue to offer in the future, but are the final and complete stage of revelation offered once and for all in the past.75

The early church fathers certainly understood this connection between apostolicity and canonical books. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, recognized the unique role of the apostles: “I am not enjoining [commanding] you as Peter and Paul did. They were apostles, I am condemned.”76 Likewise, the book of 1 Clement not only encourages its readers to “take up the epistle of that blessed apostle, Paul,”77 but also offers a clear reason why: “The Apostles received the Gospel for us from the Lord Jesus Christ, Jesus the Christ was sent from God. The Christ therefore is from God and the Apostles from the Christ.”78 In addition the letter refers to the apostles as “the greatest and most righteous pillars of the Church.”79 Apostolic origins were also central to early discussions about potential canonical books; for example, the Muratorian fragment rejected the so-called Pauline epistle to the Laodiceans because it was not really written by Paul. The church fathers understood a book as having apostolic origins even if it was not directly written by an apostle but nevertheless bore apostolic content and derived from the foundational period of the church. It is for this reason that Tertullian regarded Mark and Luke as “apostolic men.”80

Of course, if one of the attributes of canonicity is a book’s apostolic origins, then this entails an appeal to some external historical evidences to establish whether a book is apostolic. Needless to say, we do not have space in this volume to address the historical evidence for the apostolicity of each of the canonical books; that has been adequately done in the major commentaries and New Testament introductions (however, we will touch broadly on these historical questions at some points below). It should be noted here, however, that exploring the apostolic origins of these books not only works positively (showing they are apostolic), but also works negatively (showing that other books are not). Indeed, given that there are very few extant Christian writings outside the New Testament that can reasonably be dated to the first century, there simply are not many other potential candidates for canonicity.81 This fact alone eliminates most contenders for a spot in the canon.

But this raises questions about the use of historical evidences within the self-authenticating model. Does the use of evidences to show apostolic origins not make the same mistake as the criteria-of-canonicity model above and subject the canon to the uncertainties of modern biblical criticism? Not at all. The key difference is that in the self-authenticating model the external evidence does not stand alone as an independent standard to which Scripture must measure up. Consider the following.

a. External evidence is part of the application of Scripture. As already noted above, whenever we apply Scripture to any issue, it will inevitably involve external evidence from the world around us. But the use of such evidence is not inconsistent with the self-authenticating model because it does not stand alone but is interpreted and understood by the norm of Scripture. Indeed, the only reason we even know to look for “apostolic” books in the first place (as opposed to other kinds of books) is that Scripture is guiding our investigations. Even the earliest Christians would have used extrabiblical data as they sought to apply their understanding of the role of the apostles to their particular situation. Such data may have included simple things like whether the courier who delivered an apostolic letter was a known companion of the apostle who wrote it (e.g., Tychicus and Onesimus delivered Colossians and Philemon, Col. 4:7–9; Philem. 1:12), knowledge of a personal visit from an apostle himself where he delivered or mentioned a letter (which is information that does not come from the text of the letter!), or awareness of when or where a book was written. The latter reason was the basis for the Muratorian fragment’s rejection of the Shepherd of Hermas.82

b. External evidence can provide adequate grounds for a belief through the work of the Holy Spirit. C. S. Evans has rightly argued that although one does not need external evidence to have grounds for a belief, it would “be a mistake to argue that the Holy Spirit could not operate by means of evidence.”83 He declares, “There is no need to claim that beliefs are produced in only one manner. The Holy Spirit might produce the beliefs as basic ones, or they might be the outcome of a process that involves reflection on the evidence.”84 Thus, it is entirely appropriate for a single canonical model to have attributes that are more immediately or intuitively known (the divine qualities of a book) and attributes that are known through some awareness of external evidence (apostolic origins of a book).85 Whether a belief is basic or based on evidence, we have adequate grounds for affirming that belief if it is produced by the Holy Spirit.

c. Apostolicity is not the only attribute of canonicity. In the self-authenticating model, as opposed to the criteria-of-canonicity model, the historical evidence for apostolicity does not stand alone but stands in conjunction with the other attributes of canonicity, divine qualities and corporate reception. We have not yet explored the relationship between these three attributes, but we shall argue below that each of the three serves to confirm and reinforce the other two. For instance, since all apostolic books also bear divine qualities (by virtue of their inspiration), then divine qualities, in one sense, can function as evidence for apostolicity.

The criteria-of-canonicity model above encounters problems at precisely these points. It seeks to use extrabiblical data not in the process of applying Scripture, but in order to determine what should be Scripture in the first place. Apostolicity is not viewed as a principle supplied by the canonical books, but is viewed as an independent and external test of what constitutes a canonical book and what does not. As a result, the criteria-of-canonicity model finds itself in the unenviable position of being solely dependent on historical data and with no divine norm through which to interpret it and no testimonium to help understand it.86 Thus, the warning of Ridderbos is fitting: “Historical judgment cannot be the final and sole ground for the church’s accepting the New Testament as canonical. To accept the New Testament on that ground would mean the church would ultimately be basing its faith on the results of historical investigation.”87

C. Summary

The argument of the self-authenticating model so far is that we can know which books are canonical because God has provided the proper epistemic environment where belief in these books can be reliably formed. This environment includes not only providential exposure to the canonical books, but also the three attributes of canonicity that all canonical books possess—divine qualities, corporate reception, apostolic origins—and the work of the Holy Spirit to help us recognize them. Thus, contra the de jure objection, Christians do have adequate grounds for affirming their belief in the canon.

By way of example, if we want to know whether, say, 1 John is canonical, then we can apply the various components of the model. Obviously, since 1 John has been providentially exposed to the corporate church, then it is a book that the model can address. When it is examined, we can see that John’s first letter bears the attributes of canonicity.

It bears divine qualities: for example, it is a powerful writing, bears the beauty of the gospel message, and also stands in harmony with other scriptural books (this latter point has to do with the issue of “orthodoxy,” which will be discussed more below).

It has clear apostolic origins: for example, we have good historical reasons to date it to the redemptive-historical time period and to link it to the apostle John (including textual similarities to both the Gospel of John and Revelation).

It has been received by the corporate church. Not only has it been widely affirmed throughout the history of the church, but it was also recognized at the earliest stages in the development of the canon and was even included in the second-century Muratorian fragment.

And in all of these attributes, the Spirit is at work helping the believer rightly recognize their presence and validity.

Of course, this is a very quick overview of the way the model would work and would obviously be applied (in greater detail) to all twenty-seven books of the New Testament, as well as other potential candidates (e.g., 1 Clement, Shepherd of Hermas, Gospel of Thomas).88 But it is important to remember that the goal of the model is not to prove the authenticity of the canon to the skeptic. Rather, as discussed above at numerous points, our goal here is to ask whether the Christian has sufficient grounds for knowing which books God has given. Or, put differently, is the Christian’s belief about the canon justified (or warranted)?

It is also worth mentioning that this model does not imply that Christians can have some sort of infallible, incontrovertible certainty about the canon (in a Cartesian sense). Even though canonical books necessarily bear these attributes, one can always raise doubts about whether we are accurately identifying the divine qualities, reading the evidence for apostolicity correctly, and so forth. But if the model does not entail that Christians can have infallible certainty about the canon, that does not mean Christians cannot have knowledge of the canon. Most epistemologists have rejected the idea that we must have that level of certainty in order to know something—otherwise we would have very few instances of knowledge. Consider, again, our own sense perception. Does my seeing a cup on the table provide infallible certainty that a cup is indeed on the table? No, because I could be hallucinating or dreaming, or I could be a brain in a vat somewhere and electrical impulses could be making me think I see a cup on the table. But this does not require me to reject my sense perception as a reliable means of knowledge.89 In this same manner, just because a person could be mistaken about whether a book has divine qualities does not mean divine qualities are not a reliable means of identifying canonical books. Again, one can know something even if it does not rise to the level of absolute, incontrovertible certainty.

III. Implications of a Self-Authenticating Canon

Now that we have examined the major components of the self-authenticating model, we turn our attention to some implications of this model for the study of canon. We shall argue here that this model is distinctive in that (1) the attributes of canonicity relate to each other in a mutually reinforcing manner, and (2) it provides a basis for affirming multiple and complementary definitions of canon.

A. Attributes of Canonicity as Mutually Reinforcing

What is distinctive about the self-authenticating model is not just that it has three attributes of canonicity, but the way the three attributes relate to one another. These are not three independent and disconnected qualities that canonical books happen to possess, but each attribute implies and involves the other two. Thus, you cannot really speak of one attribute without, in a sense, speaking of the others. They are all bound together. Divine qualities exist only because a book is produced by an inspired apostolic author. And any book that has an apostolic author, due to the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, will inevitably contain divine qualities. In addition, any book with divine qualities (and apostolic origins) will impose itself on the church and, via the work of the testimonium, be corporately received. And if any book is corporately received by the church, then that book must possess the divine qualities that would cause the church to recognize the voice of Christ in it (again through the testimonium).90 Thus, if a book is examined that has one of these attributes, then that implies that the book also has the other two.

Because these three attributes imply one another, they work together as a unit—as a web of mutually reinforcing beliefs. Any given attribute not only implies the other two, but is also confirmed by the other two. So, apostolic origins not only imply divine qualities and corporate reception, but divine qualities and corporate reception are part of the way we know a book has apostolic origins.91 Likewise, corporate reception not only implies the existence of apostolic origins and divine qualities, but is confirmed by the existence of apostolic origins and divine qualities. And divine qualities do not simply imply apostolic origins and corporate reception, but apostolic origins and corporate reception are part of how we know a book has divine qualities. What this means is that the self-authenticating model, at its core, is both self-supporting and self-correcting. One attribute not only gets support from the other two, but can also be corrected by the other two (e.g., a person may think he recognizes divine qualities in a book, say the Shepherd of Hermas, but this is corrected by the lack of apostolic origins and corporate reception).92

The core strength of the self-authenticating model of canon, then, is the fact that it is three-dimensional. In contrast, the other models above tend to be one-dimensional and seek to authenticate canon by appealing to only a single attribute. These models are to be commended for correctly identifying attributes of canonicity, but the problem is that these attributes, biblically speaking, are not meant to work in isolation. When the three attributes are split apart, distortions are inevitable. If we only consider corporate reception in isolation, we might get the impression that canon is merely a discussion about the church and its desires and decisions—canon is just the books we prefer. If we only consider apostolic origins, we might think that the canon is all about history, facts, and historical processes. In the end, we are just left holding a bag of raw data. And if we only consider divine qualities, we might get the impression that the canon is just an instance of generic revelation given straight from heaven, with no historical manifestation at all. This not only would ignore the historical process of canonization, but would leave us with a canon that does not connect to (or come from) the real world.

The dangers inherent in absolutizing only one attribute of canonicity are apparent in Luther’s approach to canon. In his preface to James, Luther declared, “What does preach Christ is apostolic, even if Judas, Annas, Pilate, or Herod does it.”93 In this statement, it is clear that Luther is concerned foremost about a book’s orthodoxy (“what preaches Christ”). As we shall see below, orthodoxy is one of the divine qualities of Scripture. Thus, Luther has absolutized the divine qualities of canon in a manner that completely overrides a book’s apostolic origins. He is even willing to call Herod and Pilate “apostolic” as long as they preach Christ. Although it is true that orthodoxy (divine qualities) plays a role in whether we consider a particular book to be “apostolic,” it is likewise true that the apostolic origins of a book play a role in whether we consider it to be orthodox. After all, it is often a book’s connection with the apostles that gave its early readers (and now gives us) confidence that its doctrine is to be received as “orthodox.” Thus, books from Judas or Pilate or Herod, regardless of their content, would not be considered canonical. So, it is overly simplistic to argue that orthodoxy always determines apostolicity, or to argue that apostolicity always determines orthodoxy—both interact with one another and, in a sense, need one another.

A helpful historical example of the intertwined nature of orthodoxy and apostolicity is that of Serapion, Bishop of Antioch (c. 200). Upon examination of the Gospel of Peter, which was being read by some at the church at Rhossus, Serapion determined that Peter did not write it and said, “We receive both Peter and the other apostles as Christ, but the writings which falsely bear their names we reject.”94 Although Serapion’s concern for apostolic authorship here is fairly clear, some have attempted to show that Serapion’s rejection of the Gospel of Peter was only because it was promoting false doctrine (probably docetism), not because it was not written by Peter.95 In this particular historical scenario, however, it seems evident that both authorship (apostolic origins) and orthodoxy (divine qualities) were in play, one affecting the other.96 J. A. T. Robinson sums it up well: “Though the motive of [Serapion’s] condemnation of [the Gospel of Peter] was the docetic heresy that he heard it was spreading, the criterion of his judgment, to which he brought the expertise in these matters that he claimed, was its genuineness as the work of the apostle.”97

In the end, the self-authenticating model of canon actually serves to unite the various canonical models by acknowledging that no one attribute is ultimate. Because these three attributes are so interdependent, one can look at the entire question of canon through the lens of just one attribute. Thus, in a sense, all three attributes are about apostolic origins. Apostolic origins are not only about the historical background of a book, but also about the qualities produced by apostolic origins and how it leads to corporate reception in the church. Likewise, all three attributes are, in a sense, about divine qualities. Divine qualities are not only about the internal marks of a book, but also about where the divine qualities come from and the impact those qualities have on the church. And, in a sense, all three attributes are about corporate reception. Corporate reception is not only about the response of the church to a book, but also about those things that make that response possible, namely, the divine qualities and apostolic origins of a book. Thus, all three attributes are critical if we are to have a biblical understanding of canon.

In sum, we can diagram the self-authenticating model of canon as shown in figure 1.

B. Balanced Definition of Canon

Once the self-authenticating model is understood, it can shed new light on the ongoing debate over the formal definition of canon. We noted above that canon can be defined in three different ways: exclusive (canon as reception), functional (canon as use), and ontological (canon as divinely given). These three definitions for canon generally correspond to the three attributes of canonicity in the self-authenticating model. If one looks at the canon from the perspective of corporate reception, then canon is most naturally defined as the books received and recognized by the consensus of the church (exclusive).98 If one looks at the canon from the perspective of divine qualities, then canon is most naturally defined as those books that are used as authoritative revelation by a community (functional). And if one looks at the canon from the perspective of apostolic origins, then the canon is most naturally defined as those books given by God as the redemptive-historical deposit (ontological). The self-authenticating model, then, accommodates all three definitions of canon and acknowledges that each of them has appropriate applications and uses. Biblically speaking, there is no need to choose between these definitions (and their corresponding dates) because each of them captures a true attribute of canon and also implies the other two. It is only when certain canonical models absolutize just one of these three definitions (e.g., Sundberg’s exclusive definition) that distortions can arise.

As noted in prior chapters, these three definitions of canon also have implications for the historical date assigned to the origins of the canon. When did the New Testament books become canonical according to the self-authenticating model? It depends upon which definition one uses. On the exclusive definition, we do not have a canon until the third or fourth century. On the functional definition, the extant evidence suggests that we certainly have a canon by the mid-second century (if not before). On the ontological definition, a New Testament book would be canonical as soon as it was written, giving a first-century date for the canon. When these three dates are viewed as a whole, they nicely capture the entire flow of canonical history: (1) God gives his books through his apostles; Û (2) the books are recognized and used as Scripture by early Christians; Û (3) the corporate church achieves a consensus around these books. The fact that these three dates are linked in such a natural chronological order reminds us that the story of the canon is indeed a process, and therefore it should not be artificially restricted to one moment in time. Put differently, the story of the canon is less like a dot and more like a line. If so, perhaps we should consider a shift in terminology. Rather than a myopic focus on the “date” of canon (and the ensuing debates that creates), perhaps it would be better to focus on the “stage” of canon. The former term suggests that canon can mean only one thing, whereas the latter term suggests that canon has a multidimensional meaning.

These three definitions of canon can be further illuminated by modern discussions in speech-act philosophy.99 Speaking (and therefore divine speaking) can take three different forms: (1) locution (making coherent and meaningful sounds or, in the case of writing, letters); (2) illocution (what the words are actually doing; e.g., promising, warning, commanding, declaring, etc.); and (3) perlocution (the effect of these words on the listener; e.g., encouraging, challenging, persuading).100 Any speaking act can include some or all of these attributes. These three types of speech-acts generally correspond to the three definitions of canon outlined in the self-authenticating model. The ontological definition of canon refers to the actual writing of these books in redemptive history and thus refers to a locutionary act. The functional definition refers to what the canonical books do as authoritative documents and thus refers to an illocutionary act. And the exclusive definition refers to the reception and impact of these books on the church and thus envisions a perlocutionary act.

Speech-act theory helps clarify, once again, that the disagreements over the definition of canon often prove to be a matter of emphasis in any given canonical model. For example, the community-determined models tend toward viewing canon as a perlocutionary act and, therefore, often resist calling something canon until there is an impact or response from the believing community. This goes a long way, for example, toward explaining the existential/neoorthodox model of canon, particularly in its Barthian manifestation. As noted above, Barth’s doctrine of Scripture emphasizes revelation as an “event” that happens to individuals when the Spirit illumines them and they experience the word of God. Thus, it is no surprise that canon exists only when there is a response from the community. Although there are residual concerns about Barth’s doctrine of Scripture (as discussed earlier), he is correct on this important point: canon has a perlocutionary dimension to it.101

With these considerations in mind, if we are to offer a formal definition of canon for the self-authenticating model, it would be as follows: The New Testament canon is the collection of apostolic writings that is regarded as Scripture by the corporate church. Of course, as we use the word canon throughout this study, we may focus upon just one of the three aspects of this definition at any given time. Therefore, it is important that the reader carefully note the following: while all canonical books (eventually) have all three attributes of canonicity, the term canon can still be used for a book before it has all three attributes of canonicity. For example, the Gospel of John was “canon” ten minutes after it was written even though it was not yet received by the corporate church. Again, the self-authenticating model is not arguing that the corporate reception of the church makes a book canonical. This stands in contrast with the community-determined models, which often make a book’s canonicity contingent on corporate reception. Instead, this model argues that a book can be canonical prior to corporate reception, but cannot be canonical if it never has corporate reception.

IV. Potential Defeaters of a Self-Authenticating Canon

The essence of the self-authenticating model is that Christians have a rational basis (or warrant) for affirming the twenty-seven books of the New Testament canon because God has created the proper epistemic environment wherein belief in the canon can be reliably formed. However, that is not all that needs to be said. Even if one has a rational basis for holding to a belief, that belief still faces the possibility of epistemic defeat by other beliefs that one might come to hold. Such “defeaters” are the kind of beliefs that would challenge or undercut a prior belief, giving one reason to think that the prior belief is false.102 For example, imagine John wakes up in the morning, and after seeing that his alarm clock says 9:00 a.m., he forms the belief that he is late for work. But as he scrambles to get ready, his wife informs him that their three-year-old daughter was playing with the alarm clock the night before and likely changed the time. This new information would serve as a defeater for John’s prior belief that he was late for work, even though that prior belief was entirely justified.

Likewise, when it comes to our belief in the New Testament canon, there are potential defeaters that might serve to bring doubt upon the grounds of our belief. In a volume this size it is not possible to mention all potential canonical defeaters, so we will focus upon the primary ones. These primary defeaters are usually designed to challenge the attributes of canonicity discussed above and whether these attributes really provide a means of identifying canonical books. The three main defeaters are the following:

The challenge to divine qualities: apparent disagreements and/or contradictions between New Testament books. This defeater is designed to argue against the existence of divine qualities in these books. If New Testament books are inconsistent with one another—as many scholars have claimed—then how could they really be from God? How could canonical books bear internal marks of their divinity if they prove to be a disparate collection of writings with different theologies and different doctrines?

The challenge to apostolic origins: a number of New Testament books were not written by apostles. Although we have argued here that all canonical books are apostolic, much of modern scholarship argues that a number of our New Testament books are pseudonymous forgeries. For instance, of all of Paul’s epistles, only seven are widely regarded as authentic (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon). In the face of such claims, how can we claim that all canonical books are apostolic?

The challenge to corporate reception: there was widespread disagreement in the early church that lasted well into the fourth century (and beyond). In this chapter we have argued that the consensus of the corporate church is part of how we identify canonical books because such books would have imposed themselves on the church via the work of the Holy Spirit. But is the significance of the consensus of the church not called into question when we recognize the widespread disagreement and confusion that existed in early Christianity about the extent of the canon? If the church experienced disarray over canonical books from the very start, should this not raise doubts about whether the Spirit was really at work? Moreover, there are segments of the church still today that have a different New Testament canon (e.g., the Syrian Orthodox Church has a twenty-two-book canon). Are we to think that these churches do not have the Spirit?

These potential defeaters raise important questions about the canon that, unfortunately, cannot be addressed adequately in a single volume. Nevertheless, we will attempt to provide at least a preliminary response to each of them throughout the remaining chapters. In addition to responding to these defeaters, the rest of this volume will also probe deeper into each of the three attributes of canonicity and how they help us understand the origins and development of the New Testament.

Chapter 3 of the book Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books Copyright © 2012 by Michael J. Kruger. Posted with permisssion.

ENDNOTES

1 R. Gaffin, “The New Testament as Canon,” in Inerrancy and Hermeneutic, ed. Harvey M. Conn (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 170.

2 H. N. Ridderbos, Redemptive History and the New Testament Scripture (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1988), 7.

3 Ibid.

4 This teaching did not start with the Reformers and can be traced back to the early Patristic period, most notably in Augustine (Conf. 6.5; 11.3). See discussion in F. H. Klooster, “Internal Testimony of the Holy Spirit,” in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, ed. W. Elwell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1984), 564–65.

5 John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960), 1.7.4–5.

6 Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, trans. George Musgrave Giger, ed. James T. Dennison Jr., 3 vols. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1992–1997), 1:89 (2.6.11).

7 Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, vol. 1, Prolegomena, ed. John Bolt, trans. John Vriend (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2003), 452.

8 Ibid., 458.

9 Ibid.

10 For a good article that describes the Scripture’s own claims, see W. Grudem, “Scripture’s Self-Attestation and the Problem of Formulating a Doctrine of Scripture,” in Scripture and Truth, ed. D. A. Carson and J. D. Woodbridge (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1992), 19–59; this type of self-attestation was also the major focus of B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1948).

11 E.g., Calvin often drew a contrast between the self-authenticating marks of Scripture and the evidence from the external world (Institutes, 1.7.4; 1.8.1). This is not to suggest that Calvin was opposed to the use of evidence; on the contrary he called such evidences “useful aids” (1.8.1). Rather, the point here is simply that, for Calvin, the term “self-authenticating” would have referred to only the divine marks of Scripture.

12 Classical foundationalism, roughly speaking, argues that belief in Christianity and the Bible is not warranted unless it is first based on other beliefs; either ones that have an evidentiary basis or ones that are considered self-evident or basic (laws of logic, causality, etc.). A standard example of this position is John Locke, who believed that all beliefs we hold must be based on the evidence supplied by other facts we know that are certain. See discussion in Nicholas Wolterstorff, “Tradition, Insight and Constraint,” Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association 66 (1992): 43–57. Classical foundationalism has been roundly critiqued as fallacious by modern philosophers, primarily because belief in classical foundationalism itself cannot meet its own standards (there is no evidential or self-evident basis for it) and therefore is unwarranted (Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief [New York: Oxford, 2000], 81–99). For further critique, see also Plantinga, “Reason and Belief in God,” in Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God, ed. Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 16–93.

13 C. Stephen Evans, The Historical Christ and the Jesus of Faith: The Incarnational Narrative as History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 277. For those aware of contemporary epistemological debates, it should be clear that this volume presupposes an “externalist” account of knowledge. A person can know something without knowing how he knows it or even that he knows it. Awareness that one’s beliefs are justified (or warranted) is not necessary for those beliefs to be, in fact, justified (or warranted). For more, see Alvin Plantinga, Warrant: The Current Debate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

14 Evans, The Historical Christ and the Jesus of Faith, 274–82.

15 William Alston, “Knowledge of God,” in Faith, Reason, and Skepticism, ed. Marcus Hester (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), 42.

16 Ibid., 41.

17 J. M. Frame, The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1987), 81–85.

18 Ibid., 84.

19 By “knowledge” we mean not merely that the church was aware of the existence of these books, but also that the church actually had corporate exposure to these books and was familiar with them.

20 C. Stephen Evans, “Canonicity, Apostolicity, and Biblical Authority: Some Kierkegaardian Reflections,” in Canon and Biblical Interpretation, ed. Craig Bartholomew et al. (Carlisle: Paternoster, 2006), 157.

21 Cf. Phil. 3:1; Col. 4:16. On the former text, J. B. Lightfoot, St. Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), has a brief discussion of this passage entitled, “Lost Epistle to the Philippians?” (138–42).

22 Abraham Kuyper argues that God’s preservation of some books and not others stems from the fact that we have a “predestined Bible” or a “preconceived form of the Holy Scripture” that existed in the mind of God before it came to pass in history (Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology: Its Principles [New York: Scribner, 1898], 474). For more discussion, see R. B. Gaffin, “Old Amsterdam and Inerrancy?,” WTJ 44 (1982): 250–89, esp. 256–58.

23 Sundberg insisted on a sharp distinction between Scripture and canon until the fourth century, when there was a final, closed list of books affirmed by the church. See A. C. Sundberg, “Towards a Revised History of the New Testament Canon,” SE 4 (1968): 452–61.

24 See Richard B. Gaffin, Perspectives on Pentecost (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1979), 100.

25 This is not suggesting that the church’s recognition of a book makes it canonical. No, the church recognizes it because it is canonical; it is not canonical because the church recognizes it.