by W. J. Grier

Geneva at the beginning of the sixteenth century was a city of some thirteen thousand people. Its situation near the best Alpine passes made it an important trading center. Prof. H. D. Foster of Yale has given a picture of the city and its people:

The Genevans, in fact, were not a simple, but a complex, cosmopolitan people. There was, at this crossing of the routes of trade, a mingling of French, German and Italian stock and characteristics; a large body of clergy of very dubious morality and force; and a still larger body of burghers, rather sounder and far more energetic and extremely independent, but keenly devoted to pleasure. It had the faults and follies of a medieval city and of a wealthy center in all times and lands; and also the progressive power of an ambitious, self-governing, and cosmopolitan community.

At their worst, the early Genevans were noisy and riotous and revolutionary; fond of processions and “mummeries” (not always respectable or safe), of gambling, immorality and loose songs and dances; possibly not over-scrupulous at a commercial or political bargain; and very self-assertive and obstinate. At their best, they were grave, shrewd, business-like statesmen, working slowly but surely, with keen knowledge of politics and human nature; with able leaders ready to devote time and money to public progress; and with a pretty intelligent, though less judicious, following.

In diplomacy they were as deft, as keen at a bargain and as quick to take advantage of the weakness of competitors, as they were shrewd and adroit in business. They were thrifty, but knew how to spend well; quick-witted, and gifted in the art of party nicknames. Finally, they were passionately devoted to liberty, energetic, and capable of prolonged self-sacrifice to attain and retain what they were convinced were their rights. On the borders of Switzerland, France, Germany and Italy, they belonged in temper to none of these lands; out of their Savoyard traits, their wars, reforms and new-comers, in time they created a distinct type, the Genevese.1

Williston Walker says that “no city in Christendom had had a more eventful or stormier history than Geneva during the generation and especially during the decade preceding Calvin’s coming.” Indeed through the fifteenth century and into the third decade of the sixteenth, there were three parties contending for the control: (1) the bishop of Geneva, (2) the House of Savoy, and (3) the citizens of Geneva. The bishop was in theory the sovereign of the city under the overlordship of the Emperor. The Duke of Savoy had certain rights in the city and tried to gain control of both bishop and townsmen.

As early as 1387 the townsmen secured from the bishop the sanction of certain rights, known as “The Franchises.” The chief of these was to gather in general assembly (or council) to choose magistrates. Four syndics or magistrates were to be chosen annually and a treasurer to be elected for three years, and the judgment of cases involving the laity was taken from the bishop’s court and given to the magistrates. There speedily grew up the Little Council, composed of the four syndics with the syndics of the preceding year plus counsellors elected by the syndics in office. At first this Council varied in number, but it came to be fixed at twenty-five. It was charged with the administration of the rights of the citizens.

From 1457 there was a second Council of fifty members at first, later of sixty, to discuss and debate matters not easily dealt with in the General Council. From 1459 onward the members of this Council were named by the Little Council.

From 1527 there was a new Council called the Two Hundred, elected (from 1530 onward) by the Little Council. This Council tended to take over little by little the work of the Sixty.

In the early part of the fifteenth century the citizens had the support of the Bishop in withstanding the encroachments of the Dukes of Savoy, but toward the middle of the century the House of Savoy, as Bonivard tells us, began to “poke its nose into the bishopric of Geneva.” In 1444 Amadeus VIII of Savoy, elected counter-pope by the Council of Basel, took upon himself the bishopric of Geneva, and the House of Savoy seems to have held a controlling influence on the bishopric right into the third decade of the sixteenth century. Geneva now began to look to the confederate cities of Switzerland for help against Savoy, and in 1477 signed a treaty with Berne and Friburg, establishing political, military, and commercial relations between them.

Within the city from the beginning of the sixteenth century there was a struggle between the partisans of Savoy and those favoring the alliance with the confederate cities. On the side of Savoy there were the clergy and many of the richest citizens and families who had certain ties with the ducal house. On the other side there were the merchants and business men who had contact with the neighboring cities and the bulk of the common people who wished to be free from feudal and ecclesiastical bondage.

In 1520, before ever the Reformation touched the city, the people rose against the bishop (John, known as the “Bastard of Savoy”) who had pardoned one of his rich partisans in the city. The Duke with his soldiers seemed to have gained control of the city in 1525, but in 1526 the partisans of Savoy were defeated and a treaty was signed with Berne and Friburg. In 1527 the bishop left the city, never to return except for a few days in the summer of 1533. And the vice-dominus or agent of Savoy was expelled in 1528.

The First Preachers of the Reformation

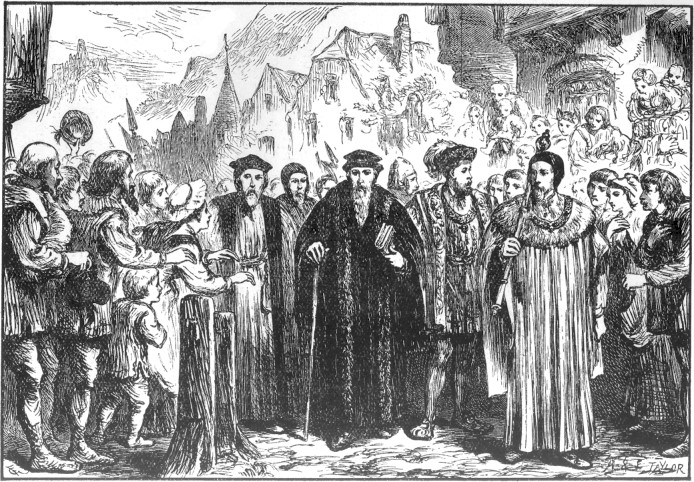

In 1529 the Emperor Charles V addressed a strong warning to the citizens of Geneva, stating that he had heard that some preachers had proclaimed Luther’s ideas among them and that this was tolerated by them. He ordered them to seize these ministers and punish them severely. William Farel visited the city in 1532 and 1533. He had to flee, but his pupil Peter Viret replaced him. Farel returned a little later and drew up a liturgy (in 1533) and a catechism or summary of faith (in 1534).

At this time, owing to the attacks and threats of Savoy, the city took the step of destroying the suburbs and erecting new walls where the suburbs had been. Apparently there was also at this time an attempt to poison the preachers—an attempt which was almost successful in the case of Viret.

By the summer of 1536 the city was coming increasingly under the control of those sympathizing with the Reformers, though a Reformed observer claimed that scarcely one-third of its inhabitants could be counted against the bishop and the Duke. Farel pressed for a public debate, to make clear to every eye the weakness of the case of their opponents. This was held between May 30 and June 24, 1535. Two Roman friars were the defenders of the Roman cause, but Farel carried the day on all points. The five points he defended make clear that Reformed doctrine was preached in Geneva before Calvin came.

On June 13, 1535, the bishop, who had fled, fulminated against the city, charging the people with listening to false preachers, renouncing the holy sacraments of Mother Church, and casting down the cross and images of our Lady. On August 10, 1535, the Council of Two Hundred decreed that the celebration of Mass cease till further notice. Most of the Roman clergy and monks fled the city. Those who wished to stay could do so on condition of attending upon the preaching of the Word of God. One contributory cause to this victory was the low morals of the Roman clergy. Prof. Foster says that “on this point there is substantial agreement between Catholic and Protestant historians.”

In February 1536, the Council of Two Hundred forbade blasphemy, oaths, and card playing, and regulated the sale of intoxicants. In June 1536 presence at the sermon was required under penalty of a fine. It is clear that there were disciplinary laws in Geneva before Calvin’s coming.

On May 21, 1536, urged on by Farel, the Little Council and the Two Hundred called a meeting of the general assembly of the citizens in the Cathedral, and there it was voted, without dissent, to live by the Word of God and abandon idolatry. They also agreed to maintain a school to which all would be obliged to send their children and where the children of the poor would be taught free of charge.

The Reformed cause was not by any means triumphant. The Genevese desired to be rid of papal abuses, but they were far from desiring with equal ardor to adhere to the new evangelical community formed in the city. There was a party which supported the Reformation, merely from patriotic and political motives—out of opposition to bishop and duke.

In 1532 when Farel first arrived, he could say: “they have little sympathy for the gospel, but are still very cold, carnal, worldly, knowing almost nothing, except taking the sacrament and speaking evil of the priests.” Calvin at the end of his life bore testimony: “When I first came to this Church, there was practically nothing. . . . There was preaching, and that is all . . . all was in confusion. . . .”

This is an accurate picture. If the city was not to fall into anarchy or come under the domination of Berne (which sought by all means to seize possession of the power formerly enjoyed by the bishop), it was necessary to accomplish a work ecclesiastical, moral, social, and political.

Calvin’s Early Reform Efforts

In January 1537, after the arrival of Calvin, the Little Council received from the ministers and adopted a document entitled “Articles concerning the organization of the Church and of Worship at Geneva.” This set of Articles was designed as a constitution for the Church, securing its existence and status. It is likely that Calvin was the principal author—possibly it was by Farel’s hand, but it expressed Calvin’s thoughts. It begins: “Most honoured lords, it is certain that a Church cannot be called well-ordered and regulated unless in it the Holy Supper of our Lord is often celebrated and attended—and this with such good discipline that none dare to present himself at it save holily and with singular reverence. And for this reason the discipline of excommunication, by which those who are unwilling to govern themselves lovingly, and in obedience to the Holy Word of God, may be corrected, is necessary to maintain the Church in its integrity.”

It is evident that behind these Articles there was a tremendous concern for that which is holy. Three leading points should be noted:

1. To enforce discipline the ministers requested that there be appointed “certain persons of good life and repute among all the faithful” to keep an eye upon the life and conduct of the citizens. These were to report notable offences to one of the ministers and join with him in fraternal admonition to the offender and as a last resort proceed to excommunication.

2. They urged in these Articles that all the inhabitants make confession and give account of their faith.

3. They urged that measures be taken to train the young in religious truth. It may be noted here that Calvin drew up a Catechism to help in this matter.

While the Little Council and the Two Hundred authorized, with slight reservations, these Articles with their far-reaching program, they showed little zeal to put them into effect. It was a common thing then for city governments to adopt rules to regulate the behavior of the citizens and then fail to enforce them. “The novel element” in the Articles of 1537, says John T. McNeill, “was the association of the restraint of private extravagance and immorality with fitness for admission to the communion.”

Opposition to the Reformers and their projects arose from various quarters: (1) those in sympathy with the old religion, (2) those seeking to be rid of the restraints of the old religion but desirous only of living according to their own pleasure, and (3) those to whom the demands of God were acceptable only in the measure in which they fitted in with their politics. These last were “nationalists” whose views were a mixture of religious faith and love for their city, the second element taking precedence of the first. At first they had favored the Reformation, but as soon as the Ref-ormation began to claim supreme place (without at the same time serving the cause of patriotism), they turned against it. So old leaders of the cause of Reform like Jean Philippe and Pierre Vandel ranged themselves against Reform. They called the Reformers “strangers.” They admired the arrangements at Berne where the Church was under the control of the State and did not claim the spiritual authority claimed in the Church of Geneva.

Calvin and Farel realized that a considerable section of the citizens was sympathetic to the old religion and stood in need of instruction. So Calvin issued his Instruction in Faith—a fine summary of the main teaching of the Institutes—and a brief Confession of Faith (presented to the magistrates in November 1536) to which all the citizens of Geneva were to be solemnly pledged. He and Farel pressed the Little Council in March, April, and May 1537 to get the citizens to express their assent, but many were unresponsive.

Berne demanded that the rites in Geneva be made uniform with her own. In Geneva under Farel’s leadership the use of baptismal fonts in the Churches and of unleavened bread in the Lord’s Supper and the keeping of such days as Christmas had been abandoned. Berne now demanded that the rites and practices followed in Geneva be made uniform with her own. On January 4, 1538, the Council of Two Hundred forbade the ministers to exclude anyone from communion, and a little later, without consulting the ministers, they adopted the Bernese ceremonies. Calvin and his colleagues in the ministry could not admit the right of the civil power to take church measures without consulting them. The result was that on February 23, 1538, he and Farel were bidden to depart within three days.

When Calvin resumed his work in Geneva on September 13, 1541, after the few years in Strasbourg, the party then in power was “weary of civil disorders, convinced of the ill-estate of the Church, and of the insufficiency of the ministers” (Williston Walker) who had taken the place of Calvin and his colleagues. They were therefore ready to give some support to Calvin’s program. On the very day of his return he asked the Little Council to adopt the principles of ecclesiastical discipline which he had instituted before his exile. Three days after this request the Little Council voted that the Ordinances to restore order in the Church and city ought to be submitted to it for approbation, then to the Two Hundred, then to the General Council. The Little Council made modifications, the Two Hundred made further modifications, and then the General Council approved of the new Constitution—without the modifications being made known to the ministers!

In these Ordinances Calvin sought to safeguard at any price the spiritual independence of the Church from the encroachment of the secular power and to put into operation an effective discipline. The Ordinances showed no essential alteration from the Articles of 1537, but were more elaborate and precise. The Councils by their alterations sought to preserve their control in Church affairs, which they often showed themselves jealous to maintain. These Ordinances of 1541 remained the moral and legal code of the city for more than three centuries (with some changes in 1561 relating particularly to marriage and excommunication).

This Constitution mentions four classes of office bearers: pastors, teachers, elders, and deacons. It laid down rules on the administration of the sacrament, on marriage, burial, visits to the sick and to prisoners, and the education of youth.

Examination of candidates for the ministry was to be in the hands of the pastors, to make sure candidates were suitable in doctrine and in life. The candidates entered upon office by the election of the ministers and the approval of the government. The Little Council changed the wording at this point to strengthen its control in the choice of ministers.

On Sundays there was to be preaching in St. Peter’s at 5 a.m. in summer and 6 a.m. in winter, in each of the three city churches at 9 a.m., and again in the afternoon in two of the three. At noon instruction was given to the children in all three. Services were held in each of the three on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday in the mornings. Before Calvin’s death a daily sermon had been instituted in all three churches in the city.

A most important provision of the Ordinances was that which required the ministers to meet weekly for discussion of the Scriptures. The exegetical exercises at these occasions were open to the public. This weekly meeting was on Fridays and was known as the Congregation. Every three months the ministers were required to meet for criticism of one another. If the ministers themselves proved unable to settle any contention which arose in their ranks, recourse should be had to the aid of the elders, and then to the magistrates. The meeting of the Venerable Company of ministers came to have a very important influence in Geneva—much greater than that actually laid down in the Ordinances.

No part of the Ordinances was more important than that concerning the office of elder. Here there was a great advance upon the Articles of 1537. The elders were to watch over the life of each individual, to admonish affectionately those who erred, and where necessary to make report to “the body which shall be appointed to make fraternal corrections.” From the first meeting of the Consistory on December 6, 1541, a new system of supervision of the life and morals of the people was introduced. People of all ages were under its inspection. Such matters as examination in religious knowledge fell within its orbit. Disciplinary measures were taken for absence from sermons, criticism of the ministers, use of charms, family quarrels, cases of drunkenness, gambling, dancing, profanity, wife-beating, and adultery. Disciplinary procedure was taken for having fortunes told by gypsies, for making a noise during sermon, for saying the pope was a good man, against a woman of seventy about to marry a youth of twenty-five, and against a barber for tonsuring a priest. This list will give some idea of the extraordinary minuteness and variety of cases reported for correction.

Calvin had not secured all that he wished in this effort for sound discipline. “It is not perfect,” he said, “but passable, considering the difficulties of the time.” He did, however, provide for the exercise of church discipline up to the point of excommunication. But that right was not fully recognized until 1554, and many a battle had to be fought before this triumph was secured.

Calvin’s Years of Struggle

In 1546 there were serious troubles for the Reformed cause in Geneva, arising specially from the Libertines, a faction which included in its ranks Genevans of easy morals. The struggle with them continued for a number of years. In 1551 it assumed fresh forms with fresh opponents—men who opposed Calvin’s doctrine and even accused him of heresy. Jerome Bolsec, for example, assailed Calvin’s teaching about predestination and charged that he was no true interpreter of Scripture.

In the summer of 1553 Calvin’s position was almost desperate. His disciplinary measures had met with resistance; the influx of refugees, who of course were his admirers, aroused jealousy and opposition. In the elections in February of that year his opponents were triumphant, his chief antagonist being elected first magistrate. Access to the General Council was refused to the ministers and the right of the consistory to excommunicate was once more challenged.

It was at this point that Servetus came to Geneva. He had written against the Trinity. More than a hundred times he called the Trinity a “monstrous three-headed Cerberus,” or dog of hell. To Protestants and Roman Catholics alike he was an extreme heretic. At Vienne he was imprisoned by the Roman Church but escaped. He was sentenced in his absence to be burned alive. John T. McNeill said recently: “Had Servetus not escaped from prison in Vienne but suffered death there under the Inquisition that condemned him, his burning would have been little noticed.”2

When he escaped from Vienne, he came to Geneva. He ventured to attend Church, was recognized, accused by Calvin, arrested, and imprisoned. The Councils of Geneva passed by the authority of Calvin and sent the case for advice to the Swiss Protestant cantons. The case against Servetus was drawn up by a notary who was an adversary of Calvin. Servetus in his turn accused Calvin of heresy and demanded his death. The day after the trial began, Berthelier, one of the leading Libertines, took up his cause. As E. M. Wilbur, the Unitarian historian, points out, the Libertines had no interest in Servetus save to embarrass Calvin. The Swiss Protestant cantons all expressed horror of Servetus’s blasphemies and advocated his punishment. Berne urged death by fire. The burning took place on October 27, 1553, Calvin’s appeal for a less cruel form of death passing unheeded. Calvin shared the opinion of his time on this matter of the punishment of heretics. After the death of Servetus he wrote on this point, urging that slight errors be borne with, that graver errors be dealt with moderately, and that the extreme penalty be reserved for blasphemous errors touching the foundation of religion. Neither he nor any of his fellow Reformers saw that their views on this point contradicted the principle of liberty of conscience.

The Triumph of Reform

The Libertines gained nothing from their support of Servetus. In fact, their leaders were discredited, and it became clearer than ever that there was a bond between sound doctrine and the maintenance of order. The influx of refugees too contributed greatly to the victory of the Reformed cause. By 1554 no less than 1,376 of them had obtained the right of residence. In the decade from 1549 to 1559, over five thousand new inhabitants were admitted, among them noble men like the Marquis of Vico, Laurence of Normandy, and Theodore Beza.

In 1554 and 1555 the cause of the Reformation was triumphant in Geneva. On February 2, 1554, the Council of Two Hundred, at Calvin’s prompting, swore with uplifted hands “to live according to the Reformation, forget all hatreds, and cultivate concord.” Later he persuaded the Little Council to adopt (like the ministers) the custom of stated meetings for mutual correction. His position at Geneva was now assured. As McNeill puts it: “Geneva was at last Calvin’s to command.”

The establishment of the Academy in 1559 was one of Calvin’s crowning attainments. To the true preaching of the Word and sound discipline was now added a sound education. “His [Calvin’s] conception of a city obedient to the will of God in Church and State, served by an educated body of ministers, disciplined by ecclesiastical watch and strict supervision, and taught by excellent schools had at last been realized” (Williston Walker).

Conclusion

The success was due to the hand of God. The walls of God’s Zion at Geneva were built in troublous times. The cause of the Reformation seemed again and again to hang by a tiny thread. Even at the end of 1553, when the triumph was not far distant, Calvin wrote to Viret: “I am broken unless God stretches forth His hand.” In 1559, the year of the founding of the Academy and the issuing of the definitive edition of the Institutes, the threat from without was so serious that ministers, nobles, and workmen toiled feverishly to repair the fortifications. They could say: “If it had not been the Lord who was on our side, the proud waters had gone over our soul.”

It was a triumph of the preaching of the Word. The Reformation began with the bold preaching of the Word by Farel and others. It was as a preacher of the Word that Calvin took up his task, and for twenty-five years he labored, often in great bodily weakness but in the Spirit’s power. At the close of his ministry, Geneva was a city of the preaching of the Word more than any city on earth.

It showed the value and efficacy of sound discipline. For a sound discipline Calvin contended through most of his ministry, and when it was established, then victory was secure. So Geneva became, as Knox said, “the most perfect school of Christ since the days of the apostles.” Knox went on: “Manners and religion to be so sincerely reformed I have not yet seen in any other place.”

There was a social, as well as a spiritual and moral, revolution. Dr. Biéler emphasizes this tremendously in his Economic and Social Thought of Calvin.3 There were measures for the care of the poor, the orphans, and the aged; and measures against overcharging and monopolies. The price of food was brought within the reach of all purses. Calvin said that if they neglected the poor, they ignored not only the poor but God whose representatives they were. The pastors of Geneva intervened to protect the weaker elements in the trades of the city, and so prevented the troubles and rebellions which broke out elsewhere. In 1560 there was the fuller organization of various trades with rules as to the conduct of masters and their relations to workers and apprentices, and hours of work were fixed and time of apprenticeship.

It was this application of the Word of God to every department of life which made out of unpromising material in Geneva what the Bishop of Ossory called “the wonderful miracle of the whole world.”

Soli Deo gloria!

Excerpt from The Puritan Papers Volume 3