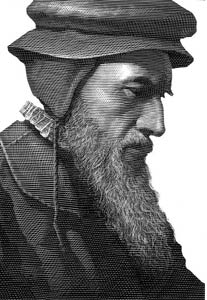

by John Calvin

by John Calvin

INTRODUCTION

A YEAR OR TWO AFTER THE WESTPHAL CONTROVERSY, there appeared another person to fish in the waters left troubled by the controversy, a certain Tilemannus Heshusius Vesalius. Bullinger seems first to have drawn Calvin's attention to the dispute in which he engaged when a teacher in Heidelberg, and later to have sent Calvin a copy of De praesentia corporis Christi in coena Domini contra sacramentarios, published by Heshusius when later resident in Magdeburg. Bullinger expressed himself unwilling to spend valuable time in refuting such trifles; and at first Calvin too seemed disinclined to accept challenge. A sudden change in opinion, however, impelled him to engage with this new adversary strenue et alacriter (C.R.), since "so great is the affront offered, that it would provoke the very stones". In 1561, accordingly, the Dilucida Explicatio was given to the world. It in turn provoked from Heshusius a Defensio against Calvin and other critics. But with this further development, the matter passes beyond the scope of this volume. (See C.R. IX, xli ff.)

The clear explanation of sound doctrine concerning the true partaking of the flesh and blood of Christ in the Holy Supper

to dissipate the mists of Tileman Heshusius

I must patiently submit to this condition which providence has assigned me, that petulant, dishonest and furious men, as if in conspiracy, pour out their virulence chiefly upon me. Other most excellent men indeed they do not spare, assailing the living and wounding the names of the dead; but the only cause of the more violent assault they make on me is because the more Satan, whose slaves they are, sees my labours to be useful to the Church of Christ, the more he stimulates them violently to attack me. I say nothing of the old pettifoggers, whose calumnies are already obsolete. A horrible apostate of the name of Staphylus has lately started up, and without a word of provocation has uttered more calumnies against me than against all the others who had described his perfidy, bad morals, and depraved disposition. From another quarter one named Nicolas Le Coq, has begun to screech against me. At length from another sink comes forth Tileman Heshusius. Of him I would rather have the reader form a judgment from the facts and his own writings than express my own opinion.

O Philip Melanchthon! for I appeal to you who live in the presence of God with Christ, and wait for us there until we are united with you in blessed rest. You said a hundred times, when, weary with labour and oppressed with sadness, you laid your head familiarly on my bosom: Would, would that I could die on this bosom! Since then, I have wished a thousand times that it had been our lot to be together. Certainly you would have been readier to maintain contests, and stronger to despise envy and make short work of false accusations. Thus too a check would have been put on the wickedness of many who grew more audacious in insult by what they called your softness. The growlings of Staphylus indeed were severely rebuked by you; but though you complained to me privately of Le Coq, as your own letter to me testifies, yet you neglected to repress his insolence and that of people like him. I have not indeed forgotten what you wrote. I will give the very words: I know that with admirable prudence you judge from the writings of your opponents what their natures are, and what audience they have in mind.

I remembered indeed what I wrote in reply to this and will quote the very words: Rightly and prudently do you remind me that the object of our antagonists is to exhibit themselves on a stage. But though their expectation will, as I hope and believe, greatly disappoint them, even if they were to win the applause of the whole world, with all the greater zeal should we be attentive to the heavenly Captain under whose eyes we fight. What? will the sacred company of angels, who both inspire us by their favour, and show us how to act strenuously by their example, allow us to grow indolent or advance hesitantly? What of the whole company of holy fathers? will they add no stimulus? What, moreover, of the Church of God which is in the world? When we know that she both aids us by her prayers, and is inspired by our example, will her assistance have no effect upon us? This be my theatre—contented with its approbation, though the whole world should hiss me, I shall never be discouraged. So far am I from envying their senseless clamour, let them enjoy their gingerbread glorifications in their obscure corner for a short time. I am not unaware what it is that the world applauds and dislikes; but to me nothing is of more consequence than to follow the rule prescribed by the Master. And I have no doubt that this ingenuousness will ultimately be more acceptable to men of sense and piety, than a soft and equivocal mode of teaching that displays empty fear. I beseech you, pay as soon as possible the debt you acknowledge is owing by you to God and the Church. I do not thus insist, because I trust some of the illwill will be thrown on you and that I shall be so far relieved. Not at all; rather for the love and respect I bear you, if it were allowable, I should willingly take part of your burden on my own shoulders. But it is for you to consider without any advice from me, that the debt will scarcely ever be paid at all, if you do not quickly remove the doubts of all the pious who look up to you. I may even add that if this late evening cockcrow does not awaken you, all men will justly cry out against you as lazy.

For this appeal to his promise, he had furnished me with an occasion by the following words: I hear that a cock from the banks of the Ister is printing a large much advertised3 volume against me; if it be published, I have determined to reply simply and without ambiguity. This labour I think I owe to God and the Church; nor in my old age have I any dread of exile and other dangers. This is ingenuously and manfully said; but in another letter he had confessed, that a temper naturally mild made him desirous of peace and quietness. His words are: As in your last letter you urge me to repress the ignorant clamour of those who renew the contest about worship of bread, I must tell you that some of those who do so are chiefly instigated by hatred to me, thinking it a plausible occasion for oppressing me. The same love of quiet prevented him from discoursing freely of other matters, whose explanation was either unpleasant to delicate palates or liable to perverse construction. But how much this saint was displeased with the importunity of those men who still cease not to rage against us is very apparent from another passage. After congratulating me on my refutation of the blasphemies of Servetus, and declaring that the Church now owed and would to posterity owe me gratitude, and that he entirely assented to my judgment, he adds that these things were of the greatest importance, and most requisite to be known, and then jestingly adds, in speaking of their silly frivolities: All this is nothing to the Artolatria.5 Writing to me at Worms, he deplores that his Saxon neighbours, who had been sent as colleagues, had left after exhibiting a condemnation of our Churches, and adds: Now they will celebrate their triumphs at home, as if for a Cadmean victory. In another letter, weary of their madness and fury, he does not conceal his desire to be with me.

The things last mentioned are of no consequence to Staphylus, who hires out his impudent tongue to the Roman Antichrist, and for the professed purpose of establishing his tyranny confounds heaven and earth after the manner of the giants. This rascal, whose base defection from the faith has left him no sense of shame, I do not regard of importance enough to occupy much time in refuting his errors. The hypothesis on which he places the whole sum and substance of his cause openly manifests his profane contempt of all religion. The whole doctrine which we profess he would bring into suspicion and so render disreputable, on the simple ground that, since the papal darkness was dissipated and eternal truth shone forth, many errors also have sprung up, which he attributes to the revival of the gospel—as if he were not thus picking a quarrel with Christ and his apostles rather than with us. The devil never stalked about so much at large, vexing both the bodies and souls of men, as when the heavenly and saving doctrine of Christ sent out its light. Let him therefore calumniously charge Christ with having come to make demoniacs of those who were formerly sane. Shortly after the first promulgation of the gospel, an incredible number of errors poured in like a deluge on the world. Let Staphylus, the hired orator of the pope, keep prating that they flowed from the gospel as their fountainhead. Assuredly if this futile calumny has any effect on feeble erring spirits, it will have none on those on whose hearts Paul's admonition is impressed: There must be heresies, in order that those who are approved may be made manifest (1 Cor. 11:19). Of this Staphylus himself is a striking proof. His brutal rage, which is plainly enough the just reward of his perfidy, confirms all the pious in the sincere fear of God. By and large the object of this vile and plainly licentious man is to destroy all reverence for heavenly doctrine; indeed the tendency of his efforts is not only to traduce religion, but to banish all care and zeal for it. Hence his dishonesty not only fails by its own demerits, but is, like its author, detested by all good men. Meanwhile, the false and ill-natured charge, by which he desired to overwhelm us, is easily rebutted on his own head. Many perverse errors have arisen during the last forty years, starting up in succession one after another. The reason is that Satan saw that by the light of the gospel the impostures by which he had long fascinated the world were overthrown, and therefore applied all his efforts and employed all his artifices, in short all his infernal powers, either to overthrow the doctrine of Christ, or interrupt its course. It was no slight attestation of the truth of God that it was thus violently assaulted by the lies of Satan. While the sudden emergence of so many impious dogmas thus gives certainty to our doctrine, what will Staphylus gain by spitting on it, unless perhaps with fickle men, who would fain destroy all distinction between good and evil?

I ask whether the many errors, about which he makes so much noise in order to vex us, went unnoticed before Luther? He himself enumerates many by which the Church was disturbed at its very beginning. If the apostles had been charged with engendering all the sects which then suddenly sprang up, would they have had no defence? But any concession thus made to them will be good for us also. However, an easier method of disposing of the reproach of Staphylus is to reply that the delirious dreams by which Satan formerly endeavoured to obscure the light of the gospel are now in a great measure suppressed; certainly scarce a tenth of them have been renewed. Since Staphylus has advertised himself for sale, were any one to pay more for him than the Pope, would he not be ready, in pure wilfulness, to reproach Christ whenever the gospel is brought forward, for bringing along with it or engendering out of it numerous errors? Never was the world more troubled with perverse and impious dogmas than at his first advent. But Christ the eternal truth of God will acquit himself without defence from us. Meanwhile, a sufficient answer to the vile charge is to be found here: there is no ground for imputing to the servants of God any part of that leaven with which Satan by his ministers corrupts pure doctrine; and therefore, to form a right judgment in such a case, it is always necessary to attend to the source in which the error originates.

Immediately after Luther began to stir up the papal cabal, many monstrous men and opinions suddenly appeared. What affinity with Luther had the Munsterians, the Anabaptists, the Adamites, the Steblerites, the Sabbatarians, the Clancularians, that they should be regarded as his disciples? Did he ever lend them his support? Did he subscribe their most absurd fictions? Rather with what vehemence did he oppose them lest the contagion spread farther? He had the discernment at once to perceive what harmful pests they would prove. And will this swine still keep grunting that the errors which were put to flight by our exertion, while all the popish clergy remained quiescent, proceeded from us? Though he is hardened in impudence, the futility of the charge will not impose itself even on children, who will at once perceive how false and unjust it is to blame us for evils which we most vehemently oppose. As it is perfectly notorious that neither Luther nor any of us ever gave the least support to those who, under the impulse of a fanatical spirit, disseminated impious and detestable errors, it is no more just that we should be blamed for their impiety than that Paul should be blamed for that of Hymenaeus and Philetus, who taught that the resurrection was past, and all further hope at an end (2 Tim. 2:17).

Moreover, what are the errors by which ignominy attaches to our whole doctrine? I need not mention how shamelessly he lies against others; to me he assigns a sect invented by himself. He gives the name of Energists to those who hold that only the virtue of Christ's body and not the body itself is in the Supper. However, he gives me Philip Melanchthon for an associate, and, to establish both assertions, refers to my writings against Westphal, where the reader will find that in the Supper our souls are nourished by the real body of Christ, which was crucified for us, and that indeed spiritual life is transferred into us from the substance of his body. When I teach that the body of Christ is given us for food by the secret energy of the Spirit, do I thereby deny that the Supper is a communion of the body? See how vilely he employs his mouth to please his patrons.

There is another monstrous term which he has invented for the purpose of inflicting a stigma upon me. He calls me bi-sacramental. But if he would make it a charge against me that I affirm that two sacraments only were instituted by Christ, he should first of all prove that he originally made them septeplex, as the papists express it. The papists obtrude seven sacraments. I do not find that Christ committed to us more than two. Staphylus should prove that all beyond these two emanated from Christ, or allow us both to hold and speak the truth. He cannot expect that his bombastic talk will make heretics of us, who rest on the sure and clear authority of the Son of God. He classes Luther, Melanchthon, myself, and many others as new Manichees, and afterwards to lengthen the catalogue repeats that the Calvinists are Manichees and Marcionites. It is easy indeed to pick up these reproaches like stones from the street, and throw them at the heads of unoffending passers-by. However, he gives his reasons for comparing us to the Manichees; but they are borrowed partly from a sodomite, partly from a cynical clown. What is the use of working to clear myself, when he indulges in the most absurd fabrications? I have no objection, however, to the challenge with which he concludes, namely to let my treatise on Predestination decide the dispute; for in this way it will soon appear what kind of thistles are produced by this wild vine.

I come now to the Cock, who with his mischievous beak declares me a corrupter of the Confession of Augsburg, denying that in the Holy Supper we are made partakers of the substance of the flesh and blood of Christ. But, as is declared in my writings more than a hundred times, I am so far from rejecting the term substance, that I simply and readily declare, that spiritual life, by the incomprehensible agency of the Spirit, is infused into us from the substance of the flesh of Christ. I also constantly admit that we are substantially fed on the flesh and blood of Christ, though I discard the gross fiction of a local compounding. What then? Because a cock is pleased to ruffle his comb against me, are all minds to be so terror-struck as to be incapable of judgment? Not to make myself ridiculous, I decline to give a long refutation of a writing which proves its author to be no less absurd than its stupid audacity proves him drunk. It certainly proclaims that when he wrote he was not in his right mind.

But what shall I do with Tileman Heshusius, who, magnificently provided with a superb and sonorous vocabulary, is confident by the breath of his mouth of laying anything flat that withstands his assault? I am also told by worthy persons who know him better that another kind of confidence inflates him: that he has made it his special determination to acquire fame by putting forward paradoxes and absurd opinions. It may be either because an intemperate nature so impels him, or because he sees in a moderate course of doctrine no place for applause left for him, for which the whole man is inflamed to madness. His tract certainly proves him to be a man of turbulent temper, as well as headlong audacity and presumption. To give the reader a sample, I shall only mention a few things from the preface. He does the very same thing as Cicero describes to have been done by the silly ranters of his day, when, by a plausible exordium stolen from some ancient oration, they aroused hope of gaining the prize. So this fine writer, to occupy the minds of his readers, collected from his master Melanchthon apt and elegant sentences by which to ingratiate himself or give an air of majesty, just as if an ape were to dress up in purple, or an ass to cover himself with a lion's skin. He harangues about the huge dangers he has run, though he has always revelled in delicacies and luxurious security. He talks of his manifold toils, though he has large treasures laid up at home, has always sold his labours at a good price, and by himself consumes all his gains. It is true, indeed, that from many places where he wished to make a quiet nest for himself, he has been repeatedly driven by his own restlessness. Thus expelled from Gossler, Rostock, Hiedelberg and Bremen, he lately withdrew to Magdeburg. Such expulsions would be meritorious, if, because of a steady adherence to truth, he had been repeatedly forced to change his habitation. But when a man full of insatiable ambition, addicted to strife and quarrelling, makes himself everywhere intolerable by his savage temper, there is no reason to complain of having been injuriously harassed by others, when by his rudeness he offered grave offence to men of right feeling. Still, however, he was provident enough to take care that his migrations should not be attended with loss; indeed riches only made him bolder.

He next bewails the vast barbarism which appears to be impending; as if any greater or more menacing barbarism were to be feared than from him and his fellows. To go no further for proof, let the reader consider how fiercely he insults and wounds his master, Philip Melanchthon, whose memory he ought to revere as sacred. He does not indeed mention him by name, but whom does he mean by the supporters of our doctrine who stand high in the Church for influence and learning, and are most distinguished theologians? Indeed, not to leave the matter to conjecture, by opprobrious epithets he points to Philip as it were with the finger, and even seems in writing his book to have been at pains to search for material for traducing him. How modest he shows himself to be in charging his preceptor with perfidy and sacrilege! He does not hesitate to accuse him of deceit in employing ambiguous terms in order to please both parties, and thus attempting to settle strife by the arts of Theramenes. Then comes the heavier charge, that he involved himself in a most pernicious crime; for the confession of faith, which ought to illumine the Church, he extinguished. Such is the pious gratitude of the scholar not only towards the master to whom he owes what learning he may possess, but towards a man who has deserved so highly of the whole Church.

When he charges me with having introduced perplexity into the discussion by my subtleties, the discussion itself will show what foundation there is for the charge. But when he calls Epicurean dogma the explanation which, both for its religious and its practical value, we give to the mystery of the Supper, what is this but to compete in scandalous libel with debauchees and pimps? Let him look for Epicurism in his own habits. Assuredly both our frugality and assiduous labours for the Church, our constancy in danger, diligence in the discharge of our office, unwearied zeal in propagating the kingdom of Christ, and integrity in asserting the doctrine of piety—in short, our serious exercise of meditation on the heavenly life, will testify that nothing is farther from us than profane contempt of God. Would that the conscience of this Thraso did not accuse him thus! But I have said more of the man than I intended.

Leaving him, therefore, my intention is to discuss briefly the matter at issue, since a more detailed discussion with him would be superfluous. For though he presents an ostentatious appearance, he does nothing more by his magniloquence than wave in the air the old follies and frivolities of Westphal and his fellows. He harangues loftily on the omnipotence of God, on putting implicit faith in his Word, and subduing human reason, as though he had learned from his betters, of whom I believe myself also to be one. From his childish and persistent self-glorification I have no doubt that he imagines himself to combine the qualities of Melanchthon and Luther. From the one he ineptly borrows flowers; and having no better way of emulating the vehemence of the other, he substitutes bombast and sound. But we have no dispute as to the boundless power of God; and all my writings declare that I do not measure the mystery of the Supper by human reason, but look up to it with devout admiration. All who in the present day contend strenuously for the honest defence of the truth, will readily admit me into their society. I have proved by fact that, in treating the mystery of the Holy Supper, I do not refuse credit to the Word of God; and therefore when Heshusius vociferates against me for doing so, he only makes all good men witnesses to his malice and ingratitude, not without grave offence. If it were possible to bring him back from vague and frivolous flights to a serious discussion of the subject, a few words would suffice.

When he alleges the sluggishness of princes as the obstacle which prevents a holy synod being assembled to settle disputes, I could wish that he himself, and similar furious individuals, did not obstruct all attempts at concord. This a little further on he does not disguise when he denies the expediency of any discussion between us. What pious synod then would suit his mind, unless one in which two hundred of his companions or thereabouts, well-fed to make their zeal more fervent, should, according to a custom which has long been common with them, declare us to be worse and more execrable than the papists? The only confession they want is the rejection of all inquiry, and the obstinate defence of any random fiction that may have fallen from them. It is perfectly obvious, though the devil has fascinated their minds in a fearful manner, that it is pride more than error that makes them so pertinacious in assailing our doctrine.

As he pretends that he is an advocate of the Church, and, in order to deceive the simple by specious masks, is always arrogating to himself the character common to all who teach rightly, I should like to know who authorized him to assume this office. He is always exclaiming: We teach; This is our opinion; Thus we speak; So we assert. Let the farrago which Westphal has huddled together be read, and a remarkable discrepancy will be found. Not to go farther for an example, Westphal boldly affirms that the body of Christ is chewed by the teeth, and confirms it by quoting with approbation the recantation of Berengarius, as given by Gratian. This does not please Heshusius, who insists that it is eaten by the mouth but not touched by the teeth, and strongly disapproves those gross modes of eating. Yet he reiterates his: We assert, just as if he were the representative of a university. This worthy son of Jena repeatedly charges me with subtleties, sophisms, even impostures: as if there were any equivocation or ambiguity, or any kind of obscurity in my mode of expression. When I say that the flesh and blood of Christ are substantially offered and exhibited to us in the Supper, I at the same time explain the mode, namely, that the flesh of Christ becomes vivifying to us, inasmuch as Christ, by the incomprehensible virtue of his Spirit, transfuses his own proper life into us from the substance of his flesh, so that he himself lives in us, and his life is common to us. Who will be persuaded by Heshusius that there is any sophistry in this clear statement, in which I at the same time use popular terms and satisfy the ear of the learned? If he would only desist from the futile calumnies by which he darkens the case, the whole point would at once be decided.

After Heshusius has exhausted all his bombast, the whole question hinges on this: Does he who denies that the body of Christ is eaten by the mouth, take away the substance of his body from the sacred Supper? I frankly engage at close quarters with the man who denies that we are partakers of the substance of the flesh of Christ, unless we eat it with our mouths. His expression is that the very substance of the flesh and blood must be taken by the mouth; but I define the mode of communication without ambiguity, by saying that Christ by his boundless and wondrous powers unites us into the same life with himself, and not only applies the fruit of his passion to us, but becomes truly ours by communicating his blessings to us, and accordingly joins us to himself, as head and members unite to form one body. I do not restrict this union to the divine essence, but affirm that it belongs to the flesh and blood, inasmuch as it was not simply said: My Spirit, but: My flesh is meat indeed; nor was it simply said: My Divinity, but: My blood is drink indeed.

Moreover, I do not interpret this communion of flesh and blood as referring only to the common nature, so that Christ, by becoming man, made us sons of God with himself by virtue of fraternal fellowship. I distinctly affirm that this flesh of ours which he assumed is vivifying for us, so that it becomes the material of spiritual life to us. I willingly embrace the saying of Augustine: As Eve was formed out of a rib of Adam, so the origin and beginning of life to us flowed from the side of Christ. And although I distinguish between the sign and the thing signified, I do not teach that there is only a bare and shadowy figure, but distinctly declare that the bread is a sure pledge of that communion with the flesh and blood of Christ which it figures. For Christ is neither a painter, nor an actor, nor a kind of Archimedes who presents an empty image to amuse the eye; but he truly and in reality performs what by external symbol he promises. Hence I conclude that the bread which we break is truly the communion of the body of Christ. But as this connection of Christ with his members depends on his incomprehensible virtue I am not ashamed to wonder at this mystery which I feel and acknowledge to transcend the reach of my mind.

Here our Thraso makes an uproar, and cries out that it is great impudence as well as sacrilegious audacity to corrupt the clear voice of God, which declares: This is my body—that one might as well deny the Son of God to be man. But I rejoin that if he would evade this very charge of sacrilegious audacity, he is on his own terms committed to anthropomorphism. He insists that no amount of absurdity must induce us to change one syllable of the words. Hence as the Scripture distinctly attributes to God feet, hands, eyes, and ears, a throne, and a footstool, it follows that he is corporeal. As he is said in the song of Miriam to be a man of war (Ex. 15:3), it will not be lawful by any fitting exposition to soften this harsh mode of expression. Let Heshusius pull on his stage boots9 if he will; his insolence must still be repressed by this strong and valid argument. The ark of the covenant is distinctly called the Lord of hosts, and indeed with such asseveration that the Prophet emphatically exclaims (Ps. 24:8): Who is this king of glory? Jehovah himself is king of hosts.

Here we do not say that the Prophet without consideration blurted out what at first glance seems absurd, as this rogue wickedly babbles. After reverently embracing what he says, piety and fittingness require the interpretation that the name of God is transferred to a symbol because of its inseparable connection with the thing and reality. Indeed this is a general rule for all the sacraments, which not only human reason compels us to adopt, but which a sense of piety and the uniform usage of Scripture dictate. No man is so ignorant or stupid as not to know that in all the sacraments the Spirit of God by the prophets and apostles employs this special form of expression. Anyone disputing this should be sent back to his rudiments. Jacob saw the Lord of hosts sitting on a ladder. Moses saw him both in a burning bush and in the flame of Mount Horeb. If the letter is tenaciously retained, how could God who is invisible be seen? Heshusius repudiates examination, and leaves us no other resource than to shut our eyes and acknowledge that God is visible and invisible. But an explanation at once clear and congruous with piety, and in fact necessary, spontaneously presents itself: that God is never seen as he is, but gives manifest signs of his presence adapted to the capacity of believers.

Thus the presence of the divine essence is not at all excluded when the name of God is by metonymy applied to the symbol by which God truly represents himself, not figuratively merely but substantially. A dove is called the Spirit. Is this to be taken strictly, as when Christ declares that God is a Spirit (Matt. 3:16; John 4:24)? Surely a manifest difference is apparent. For although the Spirit was then truly and essentially present, yet he displayed the presence both of his virtue and his essence by a visible symbol. How wicked it is of Heshusius to accuse us of inventing a symbolical body is clear from this, that no honest man infers that a symbolic Spirit was seen in the baptism of Christ because there he truly appeared under the symbol or external appearance of a dove. We declare then that in the Supper we eat the same body as was crucified, although the expression refers to the bread by metonymy, so that it may be truly said to be symbolically the real body of Christ, by whose sacrifice we have been reconciled to God. Though there is some diversity in the expressions: the bread is a sign or figure or symbol of the body, and: the bread signifies the body, or is a metaphorical or metonymical or synecdochical expression for it, they perfectly agree in substance, and therefore Westphal and Heshusius trifle when they thus look for a knot in a bulrush.

A little farther on this circus-rider says that, whatever be the variety in expression, we all hold the very same sentiments, but that I alone deceive the simple by ambiguities. But where are the ambiguities which he wants to remove and so reveal my deceit? Perhaps his rhetoric can furnish a new kind of perspicacity which will clearly manifest the alleged implications of my view. Meanwhile he unworthily includes us all in the charge of teaching that the bread is the sign of the absent body, as if I had not long ago expressly made my readers aware of two kinds of absence: they should know that the body of Christ is indeed absent in respect of place, but that we enjoy a spiritual participation in it, every obstacle on the score of distance being surmounted by his divine virtue. Hence it follows that the dispute is not about presence or about substantial eating, but about how both these are to be understood. We do not admit a presence in space, nor that gross or rather brutish eating of which Heshusius talks so absurdly, when he says that Christ in respect of his human nature is present on the earth in the substance of his body and blood, so that he is not only eaten in faith by his saints, but also by the mouth bodily without faith by the wicked.

Without adverting at present to the absurdities here involved, I ask where is the true touchstone, the express Word of God? Assuredly it cannot be found in this barbarism. Let us see, however, what the explanation is which he thinks sufficient to stop the mouths of the Calvinists—an explanation so stupid that it must rather open their mouths to protest against it. He vindicates himself and the churches of his party from the error of transubstantiation with which he falsely alleges that we charge them. For though they have many things in common with the papists, we do not therefore mix them without distinction. In fact a long time ago I showed that the papists are considerably more modest and more sober in their dreams. What does he say himself? As the words are joined together contrary to the order of nature, it is right to maintain the literal sense by which the bread is properly the body. The words therefore, to be in accordance with the thing, must be held to be contrary to the order of nature.

He afterwards excuses their different forms of expression when they assert that the body is under the bread or with the bread. But how will he convince any one that it is under the bread, except in so far as the bread is a sign? How, too, will he convince any one that the bread is not to be worshipped if it be properly Christ? The expression that the body is in the bread or under the bread, he calls improper, because the word "substantial" has its proper and genuine significance in the union of the bread and Christ. In vain, therefore, does he refute the inference that the body is in the bread, and therefore the bread should be worshipped. This inference is the invention of his own brain. The argument we have always used is this: If Christ is in the bread, he should be worshipped under the bread. Much more might we argue, that the bread should be worshipped if it be truly and properly Christ.

He thinks he gets out of the difficulty by saying, that the union is not hypostatic. But who will concede to a hundred or a thousand Heshusiuses the right to bind worship with whatever restrictions they please? Assuredly no man of sense will be satisfied in conscience with the silly quibble that the bread, though it is truly and properly Christ, is not to be worshipped, because they are not hypostatically one. The objection will at once be made that things must be the same when the one is substantially predicated of the other. The words of Christ do not teach that anything happens to the bread. But if we are to believe Heshusius and his fellows, they plainly and unambiguously assert that the bread is the body of Christ, and therefore Christ himself. Indeed they affirm more of the bread than is rightly said of the human nature of Christ. But how monstrous it is to give more honour to the bread than to the sacred flesh of Christ! Of this flesh it cannot truly be affirmed, as they insist in the case of the bread, that it is properly Christ. Though he may deny that he invents any common essence, I can always force this admission from him, that if the bread is properly the body, it is one and the same with the body. He subscribes to the sentiment of Irenaeus, that there are two different things in the Supper: an earthly and a heavenly, that is, the bread and the body. But I do not see how this can be reconciled with the fictitious identity, which, though not expressed in words, is certainly asserted in fact; for things must be the same when we can say of them: That is this, This is that.

The same reasoning applies to the local enclosing which Heshusius pretends to repudiate, when he says that Christ is not contained by place, and can be at the same time in several places. To clear himself of suspicion, he says that the bread is the body not only properly, truly, and really, but also definitively. Should I answer that I wonder what these monstrous contradictions really mean, he will meet me with the shield of Ajax—which he and his companions are accustomed to use—that reason is inimical to faith. This I readily grant if he himself is a rational animal.

Three kinds of reason are to be considered, but he at one bound leaps over them all. There is a reason naturally implanted in us which cannot be condemned without insult to God; but it has limits which it cannot overstep without being immediately lost. Of this we have a sad proof in the fall of Adam. There is another kind of vitiated reason, especially in a corrupt nature, manifested when mortal man, instead of receiving divine things with reverence, wants to subject them to his own judgment. This reason is intoxication of the mind, a kind of sweet insanity, at perpetual variance with the obedience of faith; for we must become fools in ourselves before we can begin to be wise unto God. In regard to heavenly mysteries, therefore, this reason must retire, for it is nothing better than mere fatuity, and if accompanied with arrogance rises to madness. But there is a third kind of reason, which both the Spirit of God and Scripture sanction. Heshusius, however, disregarding all distinction, confidently condemns, under the name of human reason, everything which is opposed to the frenzied dream of his own mind.

He charges us with paying more deference to reason than to the Word of God. But what if we adduce no reason that is not derived from the Word of God and founded on it? Let him show that we profanely philosophize about the mysteries of God, measure his heavenly kingdom by our sense, subject the oracles of the Holy Spirit to the judgment of the flesh, and admit nothing that does not approve itself to our own wisdom. The case is quite otherwise. For what is more repugnant to human reason than that souls, immortal by creation, should derive life from mortal flesh? This we assert. What is less in accordance with earthly wisdom, than that the flesh of Christ should infuse its vivifying virtue into us from heaven? What is more foreign to our sense, than that corruptible and fading bread should be an undoubted pledge of spiritual life? What more remote from philosophy, than that the Son of God, who in respect of human nature is in heaven, so dwells in us, that everything which has been given him of the Father is made ours, and hence the immortality with which his flesh has been endowed becomes ours? All these things we clearly testify, while Heshusius has nothing to urge but his delirious dream: the flesh of Christ is eaten by unbelievers, and yet is not vivifying. If he refuses to believe that there is any reason without philosophy, let him learn from a short syllogism:

He who does not observe the analogy between the sign and the thing signified, is an unclean animal, not having cloven hoofs;

he who asserts that the bread is truly and properly the body of Christ, destroys the analogy between the sign and the thing signified:

therefore, he who asserts that the bread is properly the body, is an unclean animal, not having cloven hoofs.

From this syllogism let him know that even though there were no philosophy in the world, he is an unclean animal. But his object in this indiscriminate condemnation of reason was no doubt to procure liberty in his own darkness, so that this inference might hold good: When mention is made of the crucifixion and of the benefits which the living and substantial body of Christ procured, the body referred to cannot be understood to be symbolical, typical, or allegorical; hence the words of Christ: This is my body, This is my blood, cannot be understood symbolically or metonymically, but substantially. As if elementary schoolboys would not see that the term symbol is applied to the bread, not to the body, and that the metonymy is not in the substance of the body, but in the context of the words. And yet he exults here as if he were an Olympic victor, and bids us try the whole force of our intellect on this argument—an argument so absurd, that I will not deign to refute it even in jest. For while he says that we turn our backs, and at the same time stimulates himself to press forward, his own procedure betrays his manifest inconsistency. He admits that we understand that the substance of the body of Christ is given, since Christ is wholly ours by faith. It is a good thing that this ox butts harmlessly at the air with his own horns, so that it is unnecessary for us to be on our guard. I would ask if we turn our backs when we thus distinctly expose his calumny in regard to an allegorical body? But as if he had fallen into a fit of forgetfulness, after he has come to himself he brings a new charge concerning absence, saying that the giving of which we speak has no more effect than the giving of a field to one who was to be immediately removed from it. How dare he thus liken the incomparable virtue of the Holy Spirit to lifeless things, and represent the gathering of the produce of a field as equivalent to that union with the Son of God, which enables our souls to obtain life from his body and blood? Surely in this matter he acts too much the rustic. I may add that it is false to say that we expound the words of Christ as if the thing were absent, when it is perfectly well known that the absence of which we speak is confined to place and actual sight. Although Christ does not exhibit his flesh as present to our eyes, nor by change of place descend from his celestial glory, we deny that this distance is an obstacle preventing him from being truly united to us.

But let us observe the kind of presence for which he contends. At first sight his view seems sane and sensible. He admits that Christ is everywhere by a communication of properties, as was taught by the fathers, and that accordingly it is not the body of Christ that is everywhere, the ubiquity being ascribed concretely to the whole person in respect of the union of the divine nature. This is so exactly our doctrine, that he might seem to be wanting by prevarication to win favour with us. Nor have we difficulty in accepting what he adds, that it is impossible to comprehend how the body of Christ is in a certain heavenly place, above the heavens, and yet the person of Christ is everywhere, ruling in equal power with the Father. Indeed the whole world knows how violently I have been assailed by his party for defending this very doctrine. To express this in a still more palpable form, I employed the trite phrase of the schools, that Christ is whole everywhere but not wholly. In other words, being entire in the person of Mediator, he fills heaven and earth, though in his flesh he be in heaven, which he has chosen as the abode of his human nature, until he appear for judgment. What then prevents us from adopting this evident distinction, and agreeing with each other? Simply that Heshusius immediately perverts what he had said, insisting that Christ did not exclude his human nature when he promised to be present on the earth. Shortly after, he says that Christ is present with his Church, dispersed in different places, and this in respect not only of his divine, but also of his human nature. In a third passage he is still plainer, and denies that there is absurdity in holding that he may, in respect of his human nature, exist in different places wherever he pleases. And he sharply rejects what he terms the physical axiom, that one body cannot be in different places. What can now be clearer than that he holds the body of Christ to be an immensity and to constitute a monstrous ubiquity? A little before he had admitted that the body is in a certain place in heaven; now he assigns it different places. This is to dismember the body, and refuse to lift up the heart.

He objects that Stephen was not carried above all the heavens to see Jesus; as if I had not repeatedly disposed of this quibble. As Christ was not recognized by his two disciples with whom he sat familiarly at the same table, not on account of any metamorphosis, but because their eyes were holden, so eyes were given to Stephen to penetrate even to the heavens. Surely it is not without cause mentioned by Luke that he lifted up his eyes to heaven, and beheld the glory of God. Nor without cause does Stephen himself declare the heavens were opened to him, that he might behold Jesus standing on the right hand of his Father. This, I fancy, makes it plain how absurdly Heshusius endeavours to bring him down to the earth. With equal shrewdness he infers that Christ was on the earth when he showed himself to Paul; as if we had never heard of that carrying up to the third heaven, which Paul himself so magnificently proclaims (2 Cor. 12:2). What does Heshusius say to this? His words are: Paul could not be translated above all heavens, whither the Son of God ascended. I have nothing to add, but that the man who thus dares to give the lie to Paul when testifying of himself merits the greatest contempt? But it is said, that as Christ distinctly offers his body in the bread, and his blood in the wine, all boldness and curiosity must be curbed. This I admit; but it does not follow that we are to shut our eyes in order to exclude the rays of the sun. Indeed, if the mystery is deserving of contemplation, it is fitting rather to consider in what way Christ can give us his body and blood for meat and drink. For if the whole Christ is in the bread, if indeed the bread itself is Christ, we may with more truth affirm that the body is Christ—an affirmation from which both piety and common sense shrink. But if we do not refuse to lift up our hearts, we shall feed on the whole Christ, as well as expressly on his flesh and blood. Indeed when Christ invites us to eat his body and to drink his blood, he need not be brought down from heaven, or required to place himself in several localities in order to put his body and his blood within our lips. The sacred bond of our union with him is amply sufficient for this purpose when by the secret virtue of the Spirit we are united into one body with him. Hence I agree with Augustine, that in the bread we receive that which hung upon the cross. But I utterly abhor the delirious fancy of Heshusius and those like him, that it is not received unless it is introduced into the carnal mouth. The communion17 of which Paul discourses does not require any local presence, unless indeed Paul, in teaching that we are called to communion with Christ (1 Cor. 1:9), either speaks of a nonentity or places Christ locally wherever the gospel is preached.

The dishonesty of this babbler is intolerable, when he says that I confine the term communion to the fellowship we have with Christ by partaking of his benefits. But before proceeding to discuss this point, it is necessary to see how ingeniously he escapes from us. When Paul says that those who eat the sacrifice are partakers17 of the altar (1 Cor. 9:13), this good fellow gives as reason, that each receives a part from the altar, and from this he concludes that my interpretation is false. But what a concoction from his own turbulent brain! Our communion, as stated by me, is not only in the fruit of Christ's death, but also in his body offered for our salvation. But this interpretation also, which he refutes as though it was different from the other, is rejected by him as excluding the presence of Christ in the Supper. Here let my readers carefully attend to the kind of presence which he imagines and to which he clings so doggedly, that he almost reduces to nothing the communion which John the Baptist had with Christ, provided he is allowed to hold that the body of Christ was swallowed by Judas. I ask this reverend doctor: if those are partakers of the altar who divide the sacrifice into parts, how can he exonerate himself from the charge of dismembering while he gives each his part? If he answers that this is not what he means, let him correct his expression. He is certainly driven from the stronghold in which all his defence was located, his assertion that I leave nothing in the Supper but a right to a thing that is absent, seeing that I uniformly maintain that through the virtue of the Spirit there is a present exhibition of a thing absent in respect of place. Still, while I refuse to subscribe to the barbarous eating by which he insists that Christ is swallowed by the mouth, he will always be swept on to abuse with his implacable fury. Verbally, indeed, he denies that he inquires concerning the mode of presence, and yet, imperiously as well as rudely, he insists on the monstrous dogma he has fabricated, that the body of Christ is eaten corporeally by the mouth. These indeed are his very words. In another passage he says: We assert not only that we become partakers of the body of Christ by faith, but that also by our mouths we receive Christ essentially or corporeally within us; and in this way we testify that we give credence to the words of Paul and the evangelists.

But we too reject the sentiments of all who deny the presence of Christ in the Supper. What then is the kind of presence for which he quarrels with us? Obviously something dreamt by himself and similar frenzied people. What impudence to cover up such gross fancies with the names of Paul and the evangelists! How will he prove to these witnesses that the body of Christ is taken by the mouth both corporeally and internally? He has elsewhere acknowledged that it is not chewed by the teeth nor touched by the palate. Why should he be so afraid of the touch of the palate or throat, while he ventures to assert that it is absorbed by the stomach? What does he mean by the expression "internally"? By what is the body of Christ received after it has passed the mouth? From the mouth, if I mistake not, the bodily passage is to the viscera or intestines. If he say that we are calumniously throwing odium on him by the use of offensive terms, I should like to know what difference there is between saying that what is received by the mouth is taken corporeally within, and saying that it passes into the viscera or intestines? Henceforth let the reader understand and be careful to remember, that whenever Heshusius charges me with denying the presence of Christ in the Supper, the only thing for which he blames me is something which seems absurd to me, that Christ is swallowed by the mouth so that he passes bodily into the stomach. Yet he complains that I play with ambiguous expressions; as if it were not my perspicuity that maddens him and his associates. Of what ambiguity can he convict me? He admits that I assert the true and substantial eating of the flesh and drinking of the blood of Christ. But, he says, when my meaning is investigated, I speak of the receiving of merit, fruit, efficacy, virtue, and power, descending from heaven. Here his malignant absurdity is not to be deduced but to be seen, when he confuses virtue and power with merit and fruit. Is it usual for any one to say that merit descends from heaven? Had he one particle of candour, he would have quoted me as either speaking or writing thus: For us to have substantial communion with the flesh of Christ, there is no necessity for any change of place, since by the secret virtue of the Spirit he infuses his life into us from heaven; nor does distance at all prevent Christ from dwelling in us, or us from being one with him, since the efficacy of the Spirit surmounts all natural obstacles.

A little farther on we shall see how shamefully he contradicts himself when he quotes my words: The blessings of Christ do not belong to us until he has himself become ours. Let him go now, and by the term merit obscure his account of the communion that I teach. He argues that if the body of Christ is in heaven he is not in the Supper, and we have symbols merely; as if the Supper were not to the true worshippers of God a heavenly action, or a kind of vehicle by which they transcend the world. But what is this to Heshusius, who not only halts on the earth, but does all he can to keep grovelling in the mud? Paul teaches that in baptism we put on Christ (Gal. 3:27). How persuasively will Heshusius argue that this cannot be if Christ remain in heaven! When Paul said this, it never occurred to him that Christ must be brought down from heaven, because he knew that he is united to us in a different manner, and that his blood is as much present to cleanse our souls as water to cleanse our bodies. If he rejoins that there is a difference between "eating" and "putting on", I answer that to put clothing on ourselves is as necessary as to take food into ourselves. Indeed the folly or malice of the man is proved by this one thing, that he admits none but a local presence. Though he denies it to be physical, and even quibbles upon the point, he yet places the body of Christ wherever the bread is, and accordingly maintains that it is in several places at the same time. As he does not hesitate so to express himself, why may not the presence to which he leads us be termed local?

Of similar stuff is his objection that the body is not received truly if it is received symbolically; as if by a true symbol we excluded the exhibition of the reality. He ultimately says it is mere imposture, unless a twofold eating is asserted, a spiritual and a corporeal. How ignorantly and erroneously he twists the passages referring to spiritual eating, I need not observe, when children can see how ridiculous he makes himself. As to the subject itself, if a division is vicious when its members coincide with each other as boys learn among the first rudiments, how will he escape the charge of having thus blundered? For if there is any eating which is not spiritual, it will follow that in the mystery of the Supper there is no operation of the Spirit. Thus it will naturally be called the flesh of Christ, just as if it were a perishable and corruptible food, and the chief earnest of eternal salvation will be unaccompanied by the Spirit. Should even this not overcome the stubborn front he offers, I ask whether independently of the use of the Supper there be no other eating than spiritual, which according to him is opposed to corporeal. He distinctly affirms that this is nothing else than faith, by which we apply to ourselves the benefits of Christ's death. What then becomes of the declaration of Paul, that we are flesh of the flesh of Christ, and bone of his bones? What will become of the exclamation: This is a great mystery (Eph. 5:30, 32)? For if beyond the application of merit, nothing is left to believers besides the present use of the Supper, the head will always be separated from the members, except at the particular moment when the bread is put into the mouth and throat. We may add on the testimony of Paul (1 Cor. 1), that fellowship with Christ is the result of the gospel no less than of the Supper. A little ago we saw Heshusius bragging of this fellowship; but what Paul affirms of the Supper he had previously affirmed of the doctrine of the gospel. If we listened to this trifler, what would become of that noble discourse in which our Saviour promises that his disciples should be one with him, as he and the Father are one? There cannot be any doubt that he there speaks of a perpetual union.

It is intolerable impudence for Heshusius to represent himself as an imitator of the fathers. He quotes a passage from Cyril on the fifteenth chapter of John; as if Cyril did not there plainly contend that the participation with Christ which is offered us in the Supper proves that we are united with him in respect of the flesh. He is disputing with the Arians, who, quoting the words of Christ: "That they may be one, as thou Father art in me and I in thee" (John 17:21), used them as pretext to deny that Christ is one with the Father in reality and essence, but only in consent. Cyril, to dispose of this quibble, answers that we are essentially one with Christ, and to prove it adduces the force of the mystical benediction. If he were contending only for a momentary communion, what could be more irrelevant? But it is no wonder that Heshusius thus betrays his utter want of shame, since he with equal confidence claims the support of Augustine, who, as all the world knows, is diametrically opposed to him. He says that Augustine distinctly admits (Serm. 2 de verb. Dom.) that there are different modes of eating the flesh, and affirms that Judas and other hypocrites ate the true flesh of Christ. But if it turn out that the epithet true is interpolated, how will Heshusius exonerate himself from a charge of forgery? Let the passage be read, and, without a word from me, it will be seen that Heshusius has forged the true flesh.

But he will say that a twofold eating is there mentioned; as if the same distinction did not everywhere occur in our writings also. Augustine there employs the terms flesh and sacrament of flesh indiscriminately in the same sense. This he has also done in several other passages. If an explanation is sought, there cannot be a clearer interpreter than himself. He says (Ep. 23 ad Bonif.) that from the resemblance which the sacraments have to the things, they often receive their names; for which reason the sacrament of the body of Christ is in a manner the body of Christ. Could he testify more clearly that the bread is termed the body of Christ indirectly because of resemblance? He elsewhere says that the body of Christ falls on the ground, but this is in the same sense in which he says that it is consumed (Hom. 26 in Joann.). Did we not here apply the resemblance formerly noticed, what could be more absurd? Indeed what a calumny it would be against this holy writer to represent him as holding that the body of Christ is taken into the stomach! It is long since I accurately explained what Augustine means by a twofold eating, namely that while some receive the virtue of the sacrament, others receive only a visible sacrament; that it is one thing to take inwardly, another outwardly; one thing to eat with the heart, another to bite with the teeth. And he finally concludes that the sacrament which is placed on the Lord's table is taken by some unto destruction and by others unto life, but the reality of which the Supper is the sign gives life to all who partake of it. In another passage also, treating in express terms of this question, he distinctly refutes those who imagined that the wicked eat the body of Christ not only sacramentally but in reality. To show our entire agreement with this holy writer, we say that those who are united by faith, so as to be his members, eat his body truly or in reality, whereas those who receive nothing but the visible sign eat only sacramentally. He often expresses himself in the very same way. (De civit. Dei, 21, ch. 25; Contra Faust. bk. 13, ch. 13; see also in Joann. ev. Tract. 25–27.)

But, as Heshusius by his importunity compels us so often to repeat, let us bring forward the passage in which Augustine says that Judas ate the bread of the Lord against the Lord, whereas the other disciples ate the bread of the Lord (in Joann. ev. Tract. 59). It is certain that this pious teacher never makes a threefold division. But why mention him alone? Not one of the fathers has taught that in the Supper we receive anything but that which remains with us after the use of the Supper.

Heshusius will exclaim that the Supper is therefore useless to us. For his words are: "Why does Christ by a new commandment enjoin us to eat his body in the Supper, and even give us bread, since not only himself but all the prophets urge us to eat the flesh of Christ by faith? Does he then in the Supper command nothing new?" I in my turn ask him: Why did God in ancient days enjoin circumcision and sacrifice and all the exercises of faith, and also why did he institute Baptism? Without his answer the explanation is quite simple: God gives no more by visible signs than by his Word, but gives in a different manner, because our weakness stands in need of a variety of helps. He asks: Will the expression not be very improper: "This cup is the New Testament in my blood," unless the whole is corporeal? To this we all answered long ago, that what is offered to us by the gospel outside the Supper is sealed to us by the Supper, and hence communion with Christ is no less truly conferred upon us by the gospel than by the Supper. He asks: How is it called the Supper of the "New Testament," if only types are exhibited in it as under the Old Testament? First, I would beg my readers to put against these silly objections the clear statements which I have made in my writings. Then they will not only find what distinction ought to be made between the sacraments of the new and of the ancient Church, but will detect Heshusius in the very act of theft, stealing everything except his own ignorant idea that nothing was given to the ancients except types. As if God had deluded the fathers with empty figures; or as if Paul's doctrine was futile, when he teaches that they ate the same spiritual food as we, and drank the same spiritual drink (1 Cor. 10:3). Heshusius at last concludes: "Unless the blood of Christ be given substantially in the Supper, it is absurd and contrary to the sacred writings to give the name of 'new covenant' to wine; and therefore there must be two kinds of eating, one spiritual and metaphorical common to the fathers, and another corporeal proper to us." It would be enough for me to deny the inference which might move even children to laughter; but how profane is the talk that contemptuously calls what is spiritual metaphorical! As if he would subject the mystical and incomprehensible virtue of the Spirit to grammarians.

Lest he should allege that he has not been completely answered, I must again repeat: As God is always true, the figures were not fallacious by which he promised his ancient people life and salvation in his only begotten Son; now, however, he plainly presents to us in Christ the things which he then showed as though from a distance. Hence Baptism and the Supper not only set Christ before us more fully and clearly than the legal rites did, but exhibit him as present. Paul accordingly teaches that we now have the body instead of shadows (Col. 2:17), not only because Christ has been once manifested, but because Baptism and the Supper, like assured pledges, confirm his presence with us. Hence appears the great distinction between, our sacraments and those of the ancient people. This, however, by no means robs them of the reality of the things which Christ today exhibits more fully, clearly, and perfectly, as from his presence one might expect.

The statement he makes so keenly and obstinately, that the unworthy eat Christ, I would leave as undeserving of refutation, except that he regards it as the chief defence of his cause. He calls it a grave matter, fit for pious and learned men to discuss together. If I grant this, how comes it that hitherto it has been impossible to obtain from his party a calm discussion of the question? If discussion is allowed, there will be no difficulty in arranging it. The arguments of Heshusius are: first, Paul distinguishes the blessed bread from common bread, not only by the article but by the demonstrative pronoun; as if the same distinction were not sufficiently made by those who call the sacred and spiritual feast a pledge and badge of our union with Christ. The second argument is: Paul more clearly asserts that the unworthy eat the flesh of Christ, when he says that they become guilty of the body and blood of Christ. But I ask whether he makes them guilty of the body as offered or as received? There is not one syllable about receiving. I admit that by partaking of the sign they insult the body of Christ, inasmuch as they reject the inestimable boon which is offered them. This disposes of the objection of Heshusius, that Paul is not speaking of the general guilt under which all the wicked lie, but teaches that the wicked by the actual taking of the body invoke a heavier judgment on themselves. It is indeed true that insult is offered to the flesh of Christ by those who with impious disdain and contempt reject it when it is held forth for food. For we maintain that in the Supper Christ holds forth his body to reprobates as well as to believers, but in such manner that those who profane the Sacrament by unworthy receiving make no change in its nature, nor in any respect impair the effect of the promise. But although Christ remains like to himself and true to his promises, it does not follow that what is given is received by all indiscriminately.

Heshusius amplifies and says that Paul does not speak of a slight fault. It is indeed no slight fault which an apostle denounces when he says that the wicked, even though they do not approach the Supper, crucify to themselves the Son of God, and put him to an open shame, and trample his sacred blood under their feet (Heb. 6:6; 10:29). They can do all this without swallowing Christ. The reader sees whether I marvellously twist and turn, as Heshusius foolishly says, involving myself in darkness from a hatred of the light, when I say that men are guilty of the body and blood of Christ in repudiating both the gifts, though eternal truth invites them to partake of them. But he rejoins that this sophism is brushed away like a spider's web by the words of Paul, when he says that they eat and drink judgment to themselves. As if unbelievers under the law did not also eat judgment to themselves, by presuming while impure and polluted to eat the paschal lamb. And yet Heshusius after his own fashion boasts of having made it clear that the body of Christ is taken by the wicked. How much more correct is the view of Augustine, that many in the crowd press on Christ without ever touching him! Still he persists, exclaiming that nothing can be clearer than the declaration that the wicked do not discern the Lord's body, and that darkness is violently and intentionally thrown on the clearest truth by all who deny that the body of Christ is taken by the unworthy. He might have some colour for this, if I denied that the body of Christ is given to the unworthy; but as they impiously reject what is liberally offered to them, they are deservedly condemned for profane and brutish contempt inasmuch as they set at nought the victim by which the sins of the world were expiated and men reconciled to God.

Meanwhile let the reader observe how suddenly heated Heshusius has become. He lately began by saying that the subject was a proper one for mutual conference between pious and learned men, but here he blazes out fiercely against all who dare to doubt or inquire. In the same way he is angry at us for maintaining that the thing which the bread figures is conferred and performed not by the minister but by Christ. Why is he not angry rather with Augustine and Chrysostom, the one teaching that it is administered by man but in a divine manner, on earth but in a heavenly manner; while the other speaks thus: Now Christ is ready; he who spread the table at which he sat now consecrates this one. For the body and blood of Christ are not made by him who has been appointed to consecrate the Lord's table, but by him who was crucified for us, and so on. I have no concern with what Heshusius adds. He says it is a fanatical and sophistical corruption to hold that by the unworthy are meant the weak and those possessed of little faith, though not wholly aliens from Christ. I hope he will find some one to answer him. But this contortionist draws me in to advocate an alien cause, in order to overwhelm me with the crime of a sacrilegious and most cruel parricide, because by my doctrine timid consciences are murdered and driven to despair.

He asks Calvinists with what faith they approach the Supper—with great or little? It is easy to give the answer furnished by the Institutes, where I distinctly refute the error of those who require a perfection nowhere to be found, and by this severity keep back from the use of the Supper, not the weak only, but those best qualified. Even children, by the form which we commonly use, are fully instructed how to refute the silly calumny. It is vain for him therefore to display his loquacity by running away from the subject. Lest he pride himself on his performance here, it is right to insert this much by the way. He says two things are diametrically opposed: forgiveness of sins and guilt before the tribunal of God. As if even the least instructed did not know that believers in the same act provoke the wrath of God, and yet by his indulgence obtain favour. We all condemn the craft of Rebecca in substituting Jacob in the place of Esau, and there is no doubt that before God the act deserved severe punishment; yet he so mercifully forgave it, that by means of it Jacob obtained the blessing. It is worth while to observe in passing how sharply he disposes of my objection as absurd, that Christ cannot be separated from his Spirit. His answer is that, since the words of Paul are clear, he assents to them. Does he mean to astonish us by a miracle when he tells us that the blind see? It has been clearly enough shown that nothing of the kind is to be seen in the words of Paul. He endeavours to disentangle himself by saying that Christ is present to his creatures in many ways. But the first thing to be explained is how Christ is present with unbelievers, to be the spiritual food of their souls, and in short the life and salvation of the world. As he adheres so doggedly to the words, I should like to know how the wicked can eat the flesh of Christ which was not crucified for them, and how they can drink the blood which was not shed to expiate their sins? I agree with him that Christ is present as a strict judge when his Supper is profaned. But it is one thing to be eaten, and another to be judge. When he later says that the Holy Spirit dwelt in Saul, we must send him back to his rudiments, that he may learn how to discriminate between the sanctification proper only to the elect and the children of God, and the general power which is proper even to the reprobate. These quibbles, therefore, do not in the slightest degree affect my axiom, that Christ, considered as the living bread and the victim immolated on the cross, cannot enter a human body devoid of his Spirit.

I think that sufficient proof has been given of the ignorance as well as the effrontery, stubbornness, and petulance of Heshusius—such proof as must not only render him offensive to men of worth and sound judgment, but make his own party ashamed of so incompetent a champion. But as he pretends to give a confirmation of his dogma, it may be worth while briefly to discuss what he advances, lest his loud boasting should impose upon the simple. I have shown elsewhere and oftener than once how irrelevant it is here to introduce harangues on the boundless power of God, since the question is not what God can do, but what kind of communion with his flesh the Author of the Supper has taught us to believe. He comes, however, to the point when he brings forward the expressions of Paul and the evangelists; only he exercises his loquacity in the absurdest calumnies, as if it were our purpose to subvert the ordinance of Christ. We have always declared, with equal good faith, sincerity and candour, that we reverently embrace what Paul and the three Evangelists teach, so long as the meaning of their words be investigated with proper soberness and modesty. Heshusius says that they all speak the same thing so much so that there is scarcely a syllable of difference. As if, in their most perfect agreement, there were not an evident variety in the form of expression which may well raise questions. Two of them call the cup the blood of the new covenant; the other two call it a new covenant in the blood. Is there here not one syllable of difference? But granting that the four employ the same words and almost the same syllables, must we forthwith concede what Heshusius affirms, that there is no figure in the words? Scripture makes mention not four times but almost a thousand times of the ears, eyes and right hand of God. If an expression four times repeated excludes all figures, will a thousand passages have no effect at all, or a less effect? Let it be that the question relates not to the fruit of Christ's passion, but to the presence of his body, provided the term presence be not restricted to place. Though I grant this, I deny that the point on which the question turns is whether the words: This is my body, are used in a proper sense or by metonymy; and therefore I hold that it is absurd of Heshusius to infer one from the other. Were any one to concede to him that the bread is called the body of Christ, because it is an exhibitive sign, and at the same time to add that it is called body, essentially and corporeally, what further ground for quarrel would he have?

The proper question, therefore, concerns the mode of communication. However, if he chooses to insist on the words, I have no objection. We must therefore see whether they are to be understood sacramentally, or as implying actual consumption. There is no dispute as to the body which Christ designates, for I have declared often enough above that I imagine no two-bodied Christ, and that therefore the body which was once crucified is given in the Supper. Indeed it is plain from my Commentaries how I have expounded the passage: "The bread which I will give is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world" (John 6:51).

My exposition is that there are two kinds of giving, because the same body which Christ once offered for our salvation he offers to us every day as spiritual food. All therefore that he says about a symbolical body is nothing better than the slander of a low-class buffoon. It is insufferable to see him blinding the eye of the reader, while fighting with the ghosts and shadows of his own imagination. Equally futile is he when he says that I keep talking only of fruit and efficacy. Everywhere I assert a substantial communion, and discard only a local presence and the figment of an immensity of flesh. But this perverse expositor cannot be appeased unless we concede to him that the words of Paul: "the cup is the new covenant in my blood," are equivalent to "the blood is contained in the cup." If this be granted, he must submit to the disgrace of retracting what he has so tenaciously asserted of the proper and natural meaning of the words. For who will be persuaded by him that there is no figure when the cup is called a covenant in blood, because it contains blood? I do not disguise, however, that I reject this foolish exposition. It does not follow from it that we are redeemed by wine, and that the saying of Christ is false; since, in order to drink the blood of Christ by faith, the thing necessary is not that he come down to earth, but that we rise up to heaven, or rather the blood of Christ must remain in heaven in order that believers may share it among themselves.

Heshusius, to deprive us of all sacramental modes of expression, maintains that we must learn, not from the institution of the passover, but from the words of Christ, what it is that is given to us in the Supper. Yet, in his dizzy way, he immediately flies off in another direction, and finds an appropriate phrase in the words: Circumcision is a covenant. But can anything be more intolerable than this pertinacious denial of the constant usage of Scripture, that the words of the Supper are to be interpreted in a sacramental manner? Christ was a rock; for he was spiritual food. The Holy Spirit was a dove. The water in Baptism is both the Spirit and the blood of Christ (otherwise it would not be the laver of the soul). Christ himself is our pass-over. While we are agreed as to all these passages, and Heshusius does not dare to deny that the forms of speech in these sacraments are similar, why, whenever the matter of the Supper is raised, does he offer such obstinate opposition? But he says that the words of Christ are clear. What greater obscurity is there in the others?

On the whole, I think I have made it clear how empty is the noise he makes, while trying to force the words of Christ to support his delirious dream. As little effect will he produce on men of sense by his arguments which he deems to be irresistible. He says that under the Old Testament all things were shadowed by types and figures, but that in the New, figures being abolished or rather fulfilled, the reality is exhibited. So be it; but can he hence infer that the water of Baptism is truly, properly, really and substantially the blood of Christ? Far more accurate is Paul (Col. 2:17), who, while he teaches that the body is now substituted for the old figures, does not mean that what was then adumbrated was completed by signs, but holds that it was in Christ himself that the substance and reality were to be sought. Accordingly, a little before, after saying that believers were circumcised in Christ by the circumcision not made with hands, he immediately adds that a pledge and testimony of this is given in Baptism, making the new sacrament correspond with the old. Heshusius after his own fashion quotes from the Epistle to the Hebrews, that the sacrifices of the Old Testament were types of the true. But the term true21 is there applied not to Baptism and the Supper, but to the death and resurrection of Christ. I have acknowledged already that in Baptism and the Supper Christ is offered otherwise than in the legal figures; but unless the reality of which the apostle there speaks is sought in a higher quarter than the sacraments, it will entirely vanish. Therefore, when the presence of Christ is contrasted with the legal shadows, it is wrong to confine it to the Supper, since the reference is to a superior manifestation wherein the perfection of our salvation consists. Even if I granted that the presence of Christ spoken of is to be referred to the sacraments of the New Testament, this would still place Baptism and the Supper on the same footing. Therefore, when Heshusius argues thus:

The sacraments of the gospel require the presence of Christ;

The Supper is a sacrament of the gospel:

Therefore, it requires the presence of Christ;

I in my turn rejoin:

Baptism is a sacrament of the gospel:

Therefore, it requires the presence of Christ.