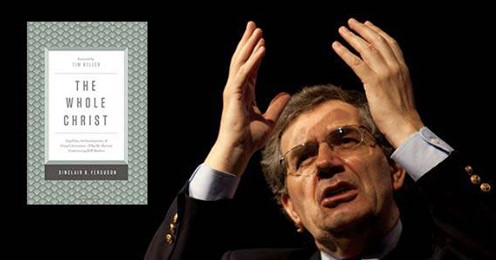

The following is chapter 8 of The Whole Christ: Legalism, Antinomianism, and Gospel Assurance - Why the Marrow Controversy Still Matters, from Crossway Books, posted with permission

by Sinclair B. Ferguson

Antinomianism takes various forms. People do not always fit neatly into our categorizations, nor do they necessarily hold all the logical implications of their presuppositions.1 Here we are using "antinomianism" in the theological sense: rejecting the obligatory ("binding on the conscience") nature of the Decalogue for those who are in Christ.

Antinomianism, it was widely assumed in the eighteenth century, is essentially a failure to understand and appreciate the place of the law of God in the Christian life. But just as there is more to legalism than first meets the eye, the same is true of antinomianism.

Opposites Attract?

Perhaps the greatest misstep in thinking about antinomianism is to think of it simpliciter as the opposite of legalism.

It would be an interesting experiment for a budding doctoral student in psychology to create a word-association test for Christians. It might include:

Old Testament - Anticipated answer - New Testament

Sin - Anticipated answer - Grace

David Anticipated answer - Goliath

Jerusalem - Anticipated answer - Babylon

Antinomianism - Anticipated answer - ?

Would it be fair to assume that the instinctive response there at the end would be "Legalism"?

Is the "correct answer" really "Legalism"? It might be the right answer at the level of common usage, but it would be unsatisfactory from the standpoint of theology, for antinomianism and legalism are not so much antithetical to each other as they are both antithetical to grace. This is why Scripture never prescribes one as the antidote for the other. Rather grace, God's grace in Christ in our union with Christ, is the antidote to both.

This is an observation of major significance, for some of the most influential antinomians in church history acknowledged they were on a flight from the discovery of their own legalism.

According to John Gill, the first biographer of Tobias Crisp, one of the father figures of English antinomianism:2 "He set out first in the legal way of preaching in which he was exceeding jealous."3

Benjamin Brook sets this in a larger context:

Persons who have embraced sentiments which afterwards appear to them erroneous, often think they can never remove too far from them; and the more remote they go from their former opinions the nearer they come to the truth. This was unhappily the case with Dr. Crisp. His ideas of the grace of Christ had been exceedingly low, and he had imbibed sentiments which produced in him a legal and self-righteous spirit. Shocked at the recollection of his former views and conduct, he seems to have imagined that he could never go far enough from them.4

But Crisp, in keeping with others, took the wrong medicine.

The antinomian is by nature a person with a legalistic heart. He or she becomes an antinomian in reaction. But this implies only a different view of law, not a more biblical one.

Richard Baxter's comments are therefore insightful:

Antinomianism rose among us from an obscure Preaching of Evangelical Grace, and insisting too much on tears and terrors.5

The wholescale removal of the law seems to provide a refuge. But the problem is not with the law, but with the heart—and this remains unchanged. Thinking that his perspective is now the antithesis of legalism, the antinomian has written an inappropriate spiritual prescription. His sickness is not fully cured. Indeed the root cause of his disease has been masked rather than exposed and cured.

There is only one genuine cure for legalism. It is the same medicine the gospel prescribes for antinomianism: understanding and tasting union with Jesus Christ himself. This leads to a new love for and obedience to the law of God, which he now mediates to us in the gospel. This alone breaks the bonds of both legalism (the law is no longer divorced from the person of Christ) and antinomianism (we are not divorced from the law, which now comes to us from the hand of Christ and in the empowerment of the Spirit, who writes it in our hearts).

Without this both legalist and antinomian remain wrongly related to God's law and inadequately related to God's grace. The marriage of duty with delight in Christ is not yet rightly celebrated.

Ralph Erskine,6 one of the leading Marrow Brethren, once said that the greatest antinomian was actually the legalist. His claim may also be true the other way around: the greatest legalist is the antinomian.

But turning from legalism to antinomianism is never the way to escape the husband whom we first married. For we are not divorced from the law by believing that the commandments do not have binding force, but only by being married to Jesus Christ in union with whom it is our pleasure to fulfill them. Boston himself is in agreement with this general analysis:

This Antinomian principle, that it is needless for a man, perfectly justified by faith, to endeavour to keep the law, and do good works, is a glaring evidence that legality is so engrained in man's corrupt nature, that until a man truly come to Christ, by faith, the legal disposition will still be reigning in him; let him turn himself into what shape, or be of what principles he will in religion; though he run into Antinomianism he will carry along with him his legal spirit, which will always be a slavish and unholy spirit.7

A century later, the Southern Presbyterian pastor and theologian James Henley Thornwell (1812–1862) noted the same principle:

Whatever form, however, Antinomianism may assume, it springs from legalism. None rush into the one extreme but those who have been in the other.8

Here, again, is John Colquhoun, speaking of the manifestation of this in the life of the true believer:

Some degree of a legal spirit or of an inclination of heart to the way of the covenant of works still remains in believers and often prevails against them. They sometimes find it exceedingly difficult for them to resist that inclination, to rely on their own attainments and performances, for some part of their title to the favor and enjoyment of God.9

If antinomianism appears to us to be a way of deliverance from our natural legalistic spirit, we need to refresh our understanding of Romans 7. In contrast to Paul, both legalists and antinomians see the law as the problem. But Paul is at pains to point out that sin, not the law is the root issue. On the contrary, the law is "good" and "righteous" and "spiritual" and "holy."10 The real enemy is indwelling sin. And the remedy for sin is neither the law nor its overthrow. It is grace, as Paul had so wonderfully exhibited in Romans 5:12–21, and that grace set in the context of his exposition of union with Christ in Romans 6:1–14. To abolish the law, then, would be to execute the innocent.

For this reason it is important to notice the dynamic of Paul's argument in Romans 7:1–6. We have been married to the law. A woman is free to marry again when her husband dies. But Paul is careful to say not that the law has died so that we can marry Christ. Rather, it is the believer who was married to the law who has died in Christ. But being raised with Christ, she is now (legally!) free to marry Christ as the husband with whom fruit for God will be brought to the birth. The entail of this second marriage is, in Paul's language, that "the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit."11

This is the sense in which the Christian's relationship to the law is that of being an "in-law"!12 We are not related to the law directly as it were, or the law in isolation as bare commandments. The relationship is dependent on and the new fruit of our prior relationship to Christ. In simple terms, just as Adam received the law from the Father, from whose hand it should never have been abstracted (as it was by the Serpent and then by Eve), so the new-covenant believer never looks at the law without understanding that his relationship to it is the fruit of his union with Christ.

Bunyan saw the meaning of Romans 7.13 An "inclination to Adam the First" remains in all of us. The believer has died to the law, but the law does not die. The law still exists to the believer. But united to Christ the believer is now able to fulfill the law of marriage and bear fruit!

Thus grace, not law, produces what the law requires; yet at the same time it is what the law requires that grace produces. Ralph Erskine sought to put this in verse form:

Thus gospel-grace and law-commands

Both bind and loose each other's hands;

They can't agree on any terms,

Yet hug each other in their arms.

Those that divide them cannot be

The friends of truth and verity;

Yet those that dare confound the two

Destroy them both, and gender woe.

This paradox none can decipher,

That plow not with the gospel heifer.14

So, he adds,

To run, to work, the law commands,

The gospel gives me feet and hands.

The one requires that I obey,

The other does the power convey.15

Head and Heart

This is a fundamental pastoral lesson. It is not merely a matter of the head. It is a matter of the heart. Antinomianism may be couched in doctrinal and theological terms, but it both betrays and masks the heart's distaste for absolute divine obligation, or duty. That is why the doctrinal explanation is only part of the battle. We are grappling with something much more elusive, the spirit of an individual, an instinct, a sinful temperamental bent, a subtle divorce of duty and delight. This requires diligent and loving pastoral care and especially faithful, union-with-Christ, full unfolding of the Word of God so that the gospel dissolves the stubborn legality in our spirits.

Olney Hymns, the hymnbook composed by John Newton and William Cowper, contains the latter's hymn "Love Constraining to Obedience," which states the situation well:

No strength of nature can suffice

To serve [the] Lord aright;

And what she has, she misapplies,

For want of clearer light.

How long beneath the law I lay

In bondage and distress!

I toil'd the precept to obey,

But toil'd without success.

Then to abstain from outward sin

Was more than I could do;

Now, if I feel its pow'r within,

I feel I hate it too.

Then all my servile works were done

A righteousness to raise;

Now, freely chosen in the Son,

I freely choose his ways.

What shall I do was then the word,

That I may worthier grow?

What shall I render to the Lord?

Is my enquiry now.

To see the Law by Christ fulfill'd,

And hear his pard'ning voice;

Changes a slave into a child,16

And duty into choice.

We are dealing here with a disposition whose roots go right down into the soil of the garden of Eden. Antinomianism then, like legalism, is not only a matter of having a wrong view of the law. It is a matter, ultimately, of a wrong view of grace, revealed in both law and gospel—and behind that, a wrong view of God himself.

But what doctrinal issues are at stake in antinomianism?

Why Then the Law?

The issue of the role of the law of God in the new covenant is a question as old as the Sermon on the Mount, as ancient as the Pastoral Epistles, and as fundamental as Paul's question: "Why then the law?"17

This was true at the time of the Reformation and during the "Second Reformation" that extended into the Puritan era. The rediscovery of covenant theology led to discussions on the nature and

role of the law. It should therefore not come as a surprise that in the biblical scholarship of the past seventy years, the rediscovery of the significance of covenant thought, both in the ancient Near East in general and in the Old Testament in particular, has been followed by a cottage industry of books and articles on the position of the law.

There are statements in the New Testament that describe the law of God with a certain harshness. Paul can speak about its role in the "ministry of death" and of the "ministry of condemnation" that was associated with it.18 Furthermore, other statements might seem to suggest that the believer is free from the law.19 This surely gives antinomianism sufficient grounds for its theological position?

There are, however, a number of important counter-considerations.

Limited Vocabulary?

In an important article written in 1964, prior to the publication of his major commentary on Romans, C. E. B. Cranfield sought to illumine the discussion of Paul's view of the law by pointing out the obvious: Paul employed no working vocabulary for legalism, legalist, or legalistic. He never used such terms. Nor did his vocabulary stretch to the term antinomian. He therefore expounded the role of, and misunderstandings of, the law without this verbal and categorical equipment.

This statement of the obvious is not, however, quite so obvious to many readers of the New Testament. There is an inbuilt tendency to assume that if a concept is present in our minds as we read Scripture, it must also have been present in the biblical author's mind. And indeed if we hold a high view of the Scriptures it may be hard for us to accept that some of our conceptual terms were simply not part of the apostolic equipment.

In this context the upshot of Paul's restricted vocabulary is that he did not employ our ready-made theological terms to express the key ideas that were later involved in the Marrow Controversy. In his own context he works within the "limitations" of the vocabulary he employs.20 Thus, writes Cranfield, Paul writes under

a very considerable disadvantage compared with the modern theologian when he is to attempt to clarify the Christian position with regard to the law.

Cranfield is not saying that Paul did not understand the law the way the church has done. But he is saying that Paul did not use the same linguistic equipment to state his view. He continues:

In view of this we should I think, be ready to reckon with the possibility that sometimes when he appeared to be disparaging the law, what he really had in mind may not be the law itself, but the misunderstanding and misuse of it for which we have a conventional term, but for which he had none.21

While Cranfield may have been right to underscore this lacuna in the commentaries, the theological point itself had been made four hundred years earlier by Calvin:

To refute their error [i.e., legalism] he [Paul] was sometimes compelled to take the bare law in a narrow sense, even though it was otherwise graced with the covenant of free adoption.22

Antinomian writers do not normally take cognizance of the exegetical and theological implications of this. But unless we are sensitive to it we will fail to unravel the proper meaning of Paul's attitude to the law.

What we discover in Paul is a simple key to understanding why he can make both pejorative and complimentary statements about the law: the ministry that produces death is a ministry of the law that in itself is "holy and righteous and good."23 Its condemning character is not the result of anything inherent in the law, but of the evil that is inherent in us.

Paul vigorously insists on this in Romans 7:7–12; indeed the whole chapter serves to clarify the nature and role of the law. He has come to know sin because of the law. Does this mean that the law itself is somehow sinful?

The passage is bookended by what appears to be an inclusio, which stresses the goodness of the law:

Question: Is the law sin(ful)?

Negatively, in verse 7, he denies that the law is sin.

Positively, in verse 12, he affirms that the law is holy, righteous, and good.

Within the inclusio he makes clear that it is sin, and not the law, that is the culprit:

Our sin is revealed by the law (v. 7b).

Our sin is also forbidden by the law (v. 7c).

Sin is in fact opportunistic with respect to the law (v. 8).

Sin comes to life in the light of the law (v. 9: like insects when a stone is lifted).

The law promised life ("Do this and live").

Sin turned the law into an instrument of death (v. 10).

Conclusion: It is sin, not the law, that kills us (v. 11)!

Thus it is in the very context in which Paul seems to take such a harsh and negative view of the law—it is the reason for his sin consciousness—that he clarifies its holy nature. It bears the very character of God himself. This is why he—and we—by faith can say, "I delight in the law of God, in my inner being."24 We must, surely, if it is holy, good, and spiritual.

The antinomian position then, which tends to take negative or pejorative statements about the law in an absolute sense, misses the biblical framework that clarifies the apostolic teaching.

The Grace of God in the Giving of the Law

It is, of course, a hermeneutical mistake so to emphasize the unity of Old and New Testaments and their respective covenants that we fail to recognize their significant diversity.

The epochal difference between the two covenants is such that John can describe it in radical terms when he writes of the Spirit's ministry: "As yet the Spirit was not since Jesus was not yet glorified."25 What is stated here in an absolute sense is, however, meant to be understood in a comparative sense.

What is true of the Spirit in John's Gospel is, by way of analogy, also true of the law. What is intended to be seen within a comparative context should not be read in absolutist terms. The law came by Moses; grace and truth came through Christ.26 This contrast is not absolute. Apart from other considerations, if it were, Christians would never admire the piety of the psalmist in Psalm 1:2 ("His delight is in the law of the Lord") or of Psalm 119:97 ("Oh how I love your law"). But the truth is that Christians instinctively desire to rise to this,27 because they recognize—at least at a subliminal level—that the law was the gracious gift of a loving Father, even if, in itself, it does not provide the power to keep it.

If the antinomian responds, "But there is more to Torah-Law than Decalogue," we must insist that while this is true, there is never less. Indeed we are entitled to ask: What is it in Torah that has been written on our minds and in our hearts in the new covenant? Can it be other than the Decalogue we are now empowered to love and keep? It cannot be the ceremonial and civil applications of it. We love the law because it is "spiritual,"28 that is, it is in harmony with the Spirit. And in the Spirit we delight in the law of God after our "inner being."29 After all, the Lord Jesus, the man of the Spirit par excellence, loved and fulfilled the law. Nor did he do this as a kenotic, to-be-tolerated-for-the-present means to an end, but because in our humanity he genuinely loved what God's Word told him God himself loved. The writing of the law in our hearts by the Spirit and the indwelling of the law-keeping Lord Jesus in our lives are the explanation of why the same becomes true for us also.

Law in the Context of Redemptive History

It is a basic presupposition in Reformed theology that the glory of God is manifested in redemptive history through the restoration of man as the image of God.30 God's salvation economy always involves the renewal of what was true of us in creation.

It is true that salvation transcends life at creation in its movement toward glorified reality. But the movement is bi-directional: back to created Eden, forward to re-created and glorified Eden; God's revelation parallels this—it keeps reworking the patterns of earlier revelation and redemption and progresses them.

Nothing is more fundamental to this than the way in which divine indicatives give rise to divine imperatives. This is the Bible's underlying grammar. Grace, in this sense, always gives rise to obligation, duty, and law. This is why the Lord Jesus himself was at pains to stress that love for him is expressed by commandment keeping.31

It is true that the New Testament teaches us about the law of love. Love is the fulfilling of the law.32 Indeed, "the whole law is fulfilled in one word: 'You shall love your neighbor as yourself.'"33 But love is never said to be a replacement for law in Scripture, for several important reasons.

The first is that love is what law commands, and the commands are what love fulfills. The law of love is not a freshly minted, newcovenant idea; it is enshrined at the heart of old-covenant faith and life. It was to be Israel's constant confession: the Lord is one, and he is to be loved in a whole-souled manner.34

The second is the often overlooked principle: love requires direction and principles of operation. Love is motivation, but it is not self-interpreting direction.

Paul's exposition of the Christian life in Romans 13:8–10 involves the significant principle that love is the fulfilling of the law. But he spells out for us that the "law" he is talking about in this context is "the commandments"—that is, the Ten Commandments. He cites four of the "neighbor love" commandments (in the order in which they appeared in his Greek Old Testament at Deut. 5:17–21). But he does not isolate these particular commandments (adultery, murder, stealing, coveting); rather he goes on to include "any other commandment."35

Commandments are the railroad tracks on which the life empowered by the love of God poured into the heart by the Holy Spirit runs. Love empowers the engine; law guides the direction. They are mutually interdependent. The notion that love can operate apart from law is a figment of the imagination. It is not only bad theology; it is poor psychology. It has to borrow from law to give eyes to love.

The Big and the Bigger Picture

We have already considered various aspects of the Bible's big picture. At Sinai God's law was given to govern his people's relationship to him ("religious" or "ceremonial" law) and also their relationship to each other in society ("civil" law). The latter was intended for them as (1) a people redeemed from Egypt, (2) while they lived in the land, (3) with a view to the coming of the Messiah.

But there is a bigger Bible picture, which extends from Sinai both backward and forward.

The exodus was itself a restoration, intended to be seen as a kind of re-creation. The people were placed in a kind of Eden—a land "flowing with milk and honey." There, as in Eden, they were given commands to regulate their lives to the glory of God.36 Grace and duty, privilege and responsibility, indicative and imperative were the order of the day as they lived before God and with one another.

In addition to or, more accurately, as the foundation of these applications, God gave them the Decalogue. It was simply a transcript in largely negative form, set within a new context in the land, of the principles of life that had constituted Adam's original existence.

Fast-forward to Calvary and the coming of the Spirit. As Moses ascended Mount Sinai and brought down the Law on tablets of stone, now Christ has ascended into the heavenly Mount, but in contrast to Moses, he has sent down the Spirit who rewrites the law not now merely on tablets of stone but in our hearts. There is a recalibration to Eden, albeit in the heart of a person formerly enslaved to sin, bearing its marks, and living in a world still under the dominion of sin. Now the empowerment is within, through the indwelling of Christ the obedient one, the law keeper, by the Spirit. This is what now provides both motivation and empowerment in the Christian. And this empowerment reduplicates in us what was true for the Lord Jesus—the ability to say, "Oh how I love your law!" Grace and law are perfectly correlated to one another.

Thus, in Christ, what was interim in Old Testament law becomes obsolete. There is an international fulfillment of the Abrahamic promise, given 430 years before Sinai.37 Now whatever in the Sinaitic covenant was intended (1) to preserve and distinguish the people as a nation in a particular land, and (2) to point them to Christ by means of ceremonies and sacraments, has ceased to be binding on the church.

But by the same token, what was the expression of God's created intention for man remains in place. Restoration to the image of God implies this. And since this is so, the Christian can no more be an antinomian than he can adopt the view that salvation is not the restoration of his life as the image of God.

Thus for the Marrow and the Brethren who appreciated it, the law written in the heart was given as part of the grace of creation. As the Marrow expressed it:

Adam heard as much (of the law) in the garden, as Israel did at Sinai; but only in fewer words, and without thunder.38

All progressive revelation echoes and advances prior revelation. This broken law was given in a specific interim formulation at Sinai. Now the same law is written in our hearts, the fruit not of creating grace, or of the commands of Sinai, but of the shed blood of Jesus. That shed blood brought Mosaic ceremonies to an end by fulfilling them; it marked the finale of the civil laws of Israel as God's people now entered a new epoch and became a spiritual nation in all lands, and no longer a socio-political people group preserved in one land.

This, then, seen from various angles, is how mainstream Reformed biblical theology saw the role of the law.

Paradoxically, today it is often statements like those of the Confession of Faith that are accused of a lack of biblical-theological perspective, for failing to understand the place of the law in redemptive history. But to this the Westminster Divines would surely be entitled to respond, "But how can you read the prophets and say they did not understand these distinctions? Were they not the mouthpieces of God, saying: 'It is not sacrifice and burnt offering that come first, but obedience'? Did they not thereby distinguish ceremonial law from moral law?"

Here again we see a parallel between Old Testament prophecy and Old Testament law. The prophets predicted the Christ who would come to save his people. But it was only when those prophecies of his coming passed through the prism of his presence that the whole truth became clear. These "unified" prophecies were in fact always looking forward to a two-stage coming of his kingdom, the first at the incarnation and the second at the consummation. So it is with the law: only in the light of Christ do we clearly see its dimensions.

As the perfect embodiment of the moral law of God, Jesus Christ bids us come to him and find rest (a term loaded with exodus echoes39). He also bids us be united to him through faith in the power of the Spirit, so that as he places his yoke (of law) on our shoulders we hear him say, "My yoke is easy and my burden is light."

So we are Ephesians 2:15–16 Christians: the ceremonial law is fulfilled.

We are Colossians 2:14–17 Christians: the civil law distinguishing Jew and Gentile is fulfilled.

And we are Romans 8:3–4 Christians: the moral law has also been fulfilled in Christ. But rather than being abrogated, that fulfillment is now repeated in us as we live in the power of the Spirit.40

In Christ then, we truly see the telos of the law. And yet as Paul also says, "Do we abrogate the law by teaching faith in Christ? No. We strengthen it. For Christ did not come to abolish it but to fulfill it, so that it might in turn be fulfilled in us." That is why in Romans 13:8–10, Ephesians 6:1, and in other places the apostle takes for granted the abiding relevance of the law of God for the life of the believer.

The Old Testament saint knew that while condemned by the law he had breached, its ceremonial provisions pointed him to the way of forgiveness. He saw Christ as really (if opaquely) in the ceremonies as he did in the prophecies. He also knew as he watched the sacrifices being offered day after day and year after year that this repetition meant these sacrifices could not fully and finally take away sin—otherwise he would not need to return to the temple precincts. He was able to love the law as his rule of life because he knew that God made provision for its breach, pointed to redemption in its ceremonies, and gave him direction through its commandments.

It should not, therefore, surprise us or grieve us to think that the Christian sees Christ in the law. He or she also sees it as a rule of life; indeed, sees with Calvin that Christ is the life of the law because without Christ there is no life in the law.

We appreciate the clarity of the law only when we gaze fully into Christ's face. But when we do gaze there, we see the face of one who said, "Oh how I love your law; it is my meditation all the day"41—and we want to be like him.

This is not—as the antinomian feared—bondage. It is freedom. The Christian rejoices therefore in the law's depth. He seeks the Spirit's guidance for its application, because he can say with Paul that in Christ through the gospel he has become an "in-law."42

At the end of the day the antinomian who regards the moral law as no longer binding is forced into an uncomfortable position. He must hold that an Old Testament believer's passionate devotion to the law (of which devotion, curiously, the majority of Christians feel they fall short) was essentially a form of legalism. But it is Jesus himself who shows an even deeper intensity in the law by expounding its deep meaning and penetration into the heart.43

Neither the Old Testament believer nor the Savior severed the law of God from his gracious person. It was not legalism for Jesus to do everything his Father commanded him. Nor is it for us.

A Tale of Two Brothers

In some ways the Marrow Controversy resolved itself into a theological version of the parable of the waiting father and his two sons.

The antinomian prodigal when awakened was tempted to legalism: "I will go and be a slave in my father's house and thus perhaps gain grace in his eyes." But he was bathed in his father's grace and set free to live as an obedient son.

The legalistic older brother never tasted his father's grace. Because of his legalism he had never been able to enjoy the privileges of the father's house.

Between them stood the father offering free grace to both, without prior qualifications in either. Had the older brother embraced his father, he would have found grace that would make every duty a delight and dissolve the hardness of his servile heart. Had that been the case, his once antinomian brother would surely have felt free to come out to him as his father had done, and say: "Isn't the grace we have been shown and given simply amazing? Let us forevermore live in obedience to every wish of our gracious father!" And arm in arm they could have gone in to dance at the party, sons and brothers together, a glorious testimony to the father's love.

But it was not so.

It is still, alas, not so.

Yet this is still true:

There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus. For the law of the Spirit of life has set you free in Christ Jesus from the law of sin and death. For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do. By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.44

And the invitation still stands:

Come, everyone who thirsts,

come to the waters;

and he who has no money,

come, buy and eat!

Come, buy wine and milk

without money and without price.

Why do you spend your money for that which is not bread,

and your labor for that which does not satisfy?

Listen diligently to me, and eat what is good,

and delight yourselves in rich food.45

This full and free offer of Christ, this dissolution of the heart bondage that evidences itself in both legalism and antinomianism, this gracious obedience to God to which our union with Christ gives rise as the Spirit writes the law into our hearts—this is still the marrow of modern divinity. Indeed it is the marrow of the gospel for us all. It is so because the gospel is Christ himself, clothed in its garments.

ENDNOTES

1 While it is important and legitimate to lay bare theological presuppositions, it is not always the case that individuals are comprehensive and consistent in following through their implications, and it is important not to impute a belief in those implications where they are in fact denied by an individual. This is an overstep common in polemical writing. It remains proper, however, to point out the logical implications of presuppositions.

2 Tobias Crisp (1600–1643) was educated at Eton and Christ's College, Cambridge, and became a fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. He was appointed rector of Newington, Surrey, and later of Brinkworth, Wiltshire, where he seems to have been a devoted pastor to his congregations. He died of smallpox in 1643, probably contracted as he diligently visited the sick. Three volumes of his sermons were soon published under the title Christ Alone Exalted. As a result of the sermons his name became associated with John Saltmarsh and others. His editor, Robert Lancaster, denied that Crisp was guilty of antinomianism, but he was viewed with suspicion by the Westminster Divines. John Gill, a predecessor of C. H. Spurgeon, was Crisp's first biographer.

3 John Gill, "Memoirs of the Life of Tobias Crisp, D. D.," in Tobias Crisp, Christ Alone Exalted, 3 vols. (London: John Bennett, 1832), 1:vi.

4 Benjamin Brook, Lives of the Puritans, 3 vols. (London, 1813), 2:473.

5 Richard Baxter, Apology for A Nonconformist Ministry (London, 1681), 226; emphasis added.

6 Ralph Erskine (1685–1782) was the younger brother of Ebenezer Erskine (1680–1754) under whose father's ministry Thomas Boston had been brought to Christ. In 1737 he followed his brother into the "Associate Presbytery," which Ebenezer and others formed in 1733 (although Ebenezer was not formally deposed from the Church of Scotland until 1740). Both brothers were among the "Representers" or Marrow Brethren. Their new denomination divided over the Burgess Oath in 1747, after which numbers of members left for the New World and became one half of the root of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (the other half being the Reformed Presbyterians, or Covenanters, who had similarly emigrated). Ralph is best known today for his Gospel Sonnets. These reflect his habit of "winding down" from his pulpit exertions at the end of the Lord's Day by turning the themes of his preaching into verse.

7 Edward Fisher, The Marrow of Modern Divinity (Ross-shire, UK: Christian Focus, 2009), 221.

8 J. H. Thornwell, The Collected Writings of James Henley Thornwell, 4 vols. (1871–1873; repr. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1974), 2:386.

9 John Colquhoun, A Treatise on the Law and Gospel, ed. D. Kistler (1859; repr. Morgan, PA: Soli Deo Gloria, 1999), 223.

10 Rom. 7:12, 14.

11 Rom. 8:4.

12 1 Cor. 9:21 (ennomos Christou).

13 See above, pp. 125–28.

14 Ralph Erskine, Gospel Sonnets or Spiritual Songs (Edinburgh: John Pryde, 1870), 288–89.

15 Ibid., 296.

16 Newton and Cowper include a footnote reference to Rom. 3:31 at this point.

17 Matt. 5:17–48; Gal. 3:19; 1 Tim. 1:8.

18 2 Cor. 3:7, 9.

19 Rom. 6:14; 7:4.

20 This point raises in its wake the large question of the relationship between the biblical text and its vocabulary and the later formulations of our Christian beliefs. It is illustrated by the term Trinity. Trinitas comes into usage only in the time of Tertullian (160–c. 225). Not only did Paul not use the term, but it did not exist in his vocabulary. But did he have the concept? If we define the concept by saying, "Trinity means that God is one ousia in three personae," it seems unlikely that this precise conceptualization was part of Paul's thinking. Does this mean Paul did not believe in the Trinity? The reverse; his letters are shot through with the substance of the later doctrine. A cursory reading of them with an eye to observing how often he coalesces the activity of the persons of the Trinity makes this overwhelmingly clear.

21 C. E. B. Cranfield, "St. Paul and the Law," Scottish Journal of Theology 17 (March 1964): 55. Much of this article is reprinted as part of an appendix ("Essay II") in C. E. B. Cranfield, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on The Epistle to the Romans, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1979), 2:845–62. In his Commentary, Cranfield writes that Paul "was surely seriously hampered in the work of clarifying the Christian position with regard to the law" (p. 853). This may not have been the most felicitous way to express the situation, but the central point is nevertheless well taken: Paul had to employ the more general vocabulary at his disposal to denote a precise concept for which he lacked the vocabulary.

22 John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. F. L. Battles, ed. J. T. McNeill (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960), 2.5.2. Cranfield notes in his commentary that he believed his point had not received attention in the literature prior to his 1964 article. Linguistically and exegetically this was probably true. But clearly theologically the implications of this had been appreciated by many theologians, as Calvin did in the way he noted the importance of a properly nuanced reading of Scripture.

23 Rom. 7:12. Note how in this context Paul goes on to explain that we miss the dynamic of the working of the law if we attribute responsibility to it that should be attributed to sin (Rom. 7:13).

24 Rom. 7:22.

25 John 7:39, literal rendering. Clearly John knows of the Spirit's presence and power prior to the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus: John 1:32; 3:5–8, 34; 6:63.

26 John 1:17

27 They do so because Jer. 31:31–33 has come to pass.

28 Rom. 7:14.

29 Rom. 7:22.

30 Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 3:18; Eph. 4:22–24; Col. 3:9–10; 1 John 3:2.

31 John 13:34; 14:23–24; 15:10, 12, 14, 17.

32 Rom. 13:10.

33 Gal. 5:14.

34 Deut. 6:5–6.

35 Rom. 13:9.

36 The tabernacle and the temple were also reflections of Eden.

37 Gal. 3:17.

38 Fisher, Marrow, 54. Note that there is not absolute identity proposed between Sinai and Eden but a real continuity rooted in the notion that the image of God is always called to reflect him; albeit the image is called to do so in differing conditions in whatever one of the "fourfold state" he or she lives: creation, fall, regeneration, or glory.

39 See: Ex. 33:14; Deut. 12:9; Josh. 1:13, 15; Isa. 63:4.

40 Here it should be noted that the New Testament contrasts the letter with the Spirit but never the substance of the moral law with the Spirit.

41 Ps. 119:97.

42 Again the principle is that he is ennomos Christou, "in-law" through his marriage to Christ. One might think here of the way in which, for example, the Rules of Golf, authoritatively issued by the United States Golf Association and The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, are never regarded as "legalistic" by those who play golf. And to be an "antinomian" golfer and ignore the rules leads to disqualification. Fascinatingly, the governing bodies of golf publish a surprisingly large book giving guidance on the details of the application of the rules to every conceivable situation on a golf course—and to some that are virtually inconceivable! The rules, and their detailed application, are intended to enhance the enjoyment of the game. My edition (2010–2011) extends to 578 pages with a further 131 pages of index. The person who loves the game of golf finds great interest and pleasure, even delight, in browsing through these applications of the Rules of Golf. It should therefore not greatly stretch the imagination that the Old Testament believer took far greater pleasure at a higher level in meditating on and walking in the ways of God's law. It is passing strange that there should be so often among Christians a sense of heart irritation against the idea that God's law should remain our delight. Our forefathers from Luther onward grasped this principle, and, as a result, through the generations those who made use of the standard catechisms learned how to apply God's Word and law to the daily details of life. It is a mysterious paradox that Christians who are so fascinated by rules and principles that are necessary or required in their professions or avocations respond to God's ten basic principles with a testy spirit. Better, surely, to say, "Oh how I love your law!" It should be no surprise that there appears to be a correlation between the demise of the law of God in evangelicalism and the rise of a plethora of mystical ways of pursuing guidance, detaching the knowledge of God's will from knowledge of and obedience to God's Word.

43 Matt. 5:17–48.

44 Rom. 8:1–4.

45 Isa. 55:1–2.

-----