by Graeme Goldsworthy

Why Read the Old Testament?

Before commencing to build our bridge, we must ask a more basic question: why bother bridging the gap in the first place? For many Christians, the problem is not how to read the Old Testament but why it should be read at all.

Why Some People Don’t Read the Old Testament

Some people still are influenced by the intellectual climate of the nineteenth century, which did much to undermine a positive appreciation of the Old Testament. The philosophical stand-point of the time led people to conclude that the Christian religion, as found in the New Testament, was nothing more than the natural evolution of man’s ideas about God. Consequently the Old Testament was regarded as a primitive, and therefore outdated, expression of religion. It was seen not only as being pre-Christian because it failed by several centuries to be concerned with the events of the gospel, but also as being sub-Christian because it failed to reach the ethical and theological heights of the New Testament. Yet many people who are quite unaffected by such ideas about the Old Testament may in practice adopt a similar attitude. For they see it as no more than a background to the teaching of the New. Perhaps they would refuse to downgrade the theological importance of the Old Testament because of their convictions about the inspiration and authority of the whole Bible. But in practice such people can be even more neglectful of the Old Testament than other Christians are, who do not hold such a high view of inspiration.

Ironically, the evangelical view of scripture itself can make the problem worse. For the ‘evolutionist’ is happy to dismiss as crude and primitive those parts of the Old Testament which he finds morally offensive. The ‘conservative’, on the other hand, has to find some way of reconciling his view of the Old Testament as the word of God with such things as … Israel’s slaughter of the Canaanites, the cursing of enemies in some psalms, or the wide prescription of capital punishment in the law of Moses. Even if parts of the Old Testament do not appear morally reprehensible to the ‘conservative’ Christian, other parts appear to be completely irrelevant.

For a third group of people, the problem with the Old Testament is simply that on the whole they find it dry and uninteresting; it is wordy, cumbersome and confusing. Whatever their view of scripture, the sheer weight and complexity of this collection of ancient books (more than three times the bulk of the New Testament) leads to boredom, apathy and neglect rather than deliberately thought-out rejection.

There is a simple way to avoid these difficulties. Our consciences are less likely to prick us for the neglect of the Old Testament if we are giving ourselves to the study of the New! After a while the Old Testament drops right out of sight and that does not cause us any pain at all.

Why Other People Do Read the Old Testament

Happily there are people who still read the Old Testament. Their conviction that the Old Testament is part of God’s written revelation is no doubt partly responsible for this. Also, if it is interpreted correctly, the Old Testament yields much to interest both young and old. Children’s speakers and designers of Sunday School curricula are amongst the most consistent users of the narratives of ancient Israel for they contain a wealth of excitement and human interest to capture the imagination of children of all ages. Tell a good story about one of Israel’s battles and you can have the kids on the edge of their seats! Yet pitfalls abound for the teacher who wants to draw out a Christian message from the Old Testament, though they may not be apparent until the unity of the Bible is understood.

False Trails

Failure to recognise the unity of Scripture led some of the early expositors to follow false trails. The emergence of the allegorical method of interpretation in the early church provides a good example. Because much of the Old Testament was seen as unhelpful or sub-Christian, the only way to save it for Christian use was to distinguish a hidden ‘spiritual’ sense, concealed behind the natural meaning.

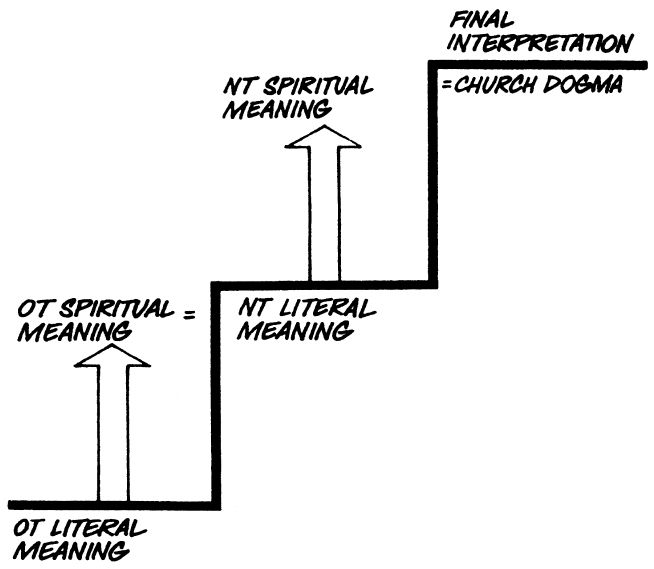

Allegory seemed to be a legitimate method of interpretation because it was controlled by the content of the New Testament or, later on, by Church dogma. What was lacking, however, was the kind of control the New Testament itself applied when it used the Old Testament. Instead the relationship between the natural meaning of the Old Testament and the teachings of the New was left to the ingenuity of the expositor. One serious effect of the allegorical method was that it tended to hinder people from taking the historical or natural sense of the Old Testament seriously.1 Nor did this problem exist only for the Old Testament. In the Middle Ages the logic was taken a step further. Not only was the ‘unhelpful’ natural sense of the Old Testament given its spiritual sense from the natural sense of the New Testament; even the natural sense of the New Testament was seen to require its own spiritual interpretation, which was found in the tradition of the church.2 Thus authority now lay, not in the natural meaning of the canon of Scripture, but in the teachings of the church as it interpreted the spiritual meaning according to its own dogma.

Figure 1 The Process of Spiritualizing

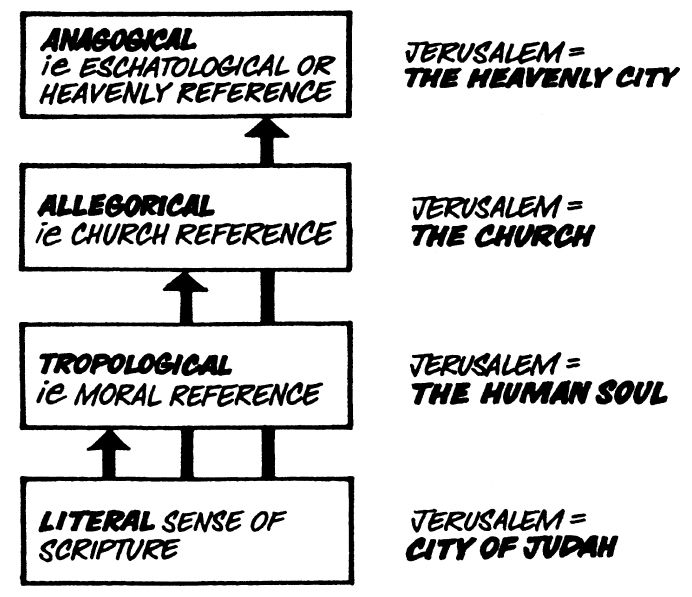

The Middle Ages saw the development of interpretation according to the four meanings of Scripture:

(a) the literal or natural meaning

(b) the moral reference to the human soul

(c) the allegorical reference to the church, and

(d) the eschatological reference to heavenly realities.

Not all texts were read with four meanings, and there was considerable activity in the field of biblical studies (especially from the 12th to the 15th centuries) as scholars sought to give proper place to the literal meaning.3

Figure 2 The Medieval Four-Fold Method of Interpretation

The Reformation Path

It was the Protestant reformers who helped the Christian church see again the importance of the historical and natural meaning of Scripture, so that the Old Testament could be regarded as having value in itself. When the reformers recovered the authority of the Bible they not only reaffirmed a biblical doctrine of the church and salvation, but also a biblical doctrine of Scripture. Protestant interpretation was based upon the concept of the perspicuous (clear and self-interpreting) nature of the Bible. By removing an authority for interpretation from outside of the Bible! – the infallible Church – the reformers were free to accept and see the principles of interpretation that are contained within the Bible itself.

So the self-interpreting scriptures became the sole rule of faith – Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone) was a rallying-cry of the Reformation. The right of interpretation was restored to every believer, but this did not mean that the principles of interpretation found within the Bible could be overlooked and every Christian follow his own whim. The allegorical method became far less popular, because the historical meaning of the Old Testament was found to be significant on its own, within the unity of the Bible.

Perhaps we understand the Protestant position better in the light of the other great principles which emerged at the Reformation. The reformers maintained that salvation is a matter of grace alone, by Christ alone, through faith alone. ‘Grace alone’ meant that salvation is God’s work alone unconditioned by anything that man is or does. ‘Christ alone’ meant that the sinner is accepted by God on the basis of what Christ alone has done. ‘Faith alone’ meant that the only way for the sinner to receive salvation is by faith whereby the righteousness of Christ is imputed (credited) to the believer.

What had this got to do with the Old Testament? It meant that the reformers were establishing a method of biblical interpretation in which the natural historical sense of the Old Testament has significance for Christians because of its organic relationship to Christ. God’s grace seen in his dealings with Israel is part of a living process which comes to its climax in his work of grace, the gospel, that is in the historical events of the Christ who is Jesus of Nazareth. Just as it is important to assert that this Old Testament ‘sacred history’ or ‘salvation history’ must be interpreted by the Word, Jesus Christ, it is also important to recognise that the gospel is God acting in history more specifically, through the history of Jesus.

Mediaeval theology had internalized and subjectivized the gospel to such an extent that the basis of acceptance with God, of justification, was no longer what God did once for all in Christ, but what God was continuing to do in the life of the Christian. This de-historicizing of what God had done once and for all in the gospel went hand-in-hand with the allegorizing of the history of the Old Testament. The Reformation recovered the historical Christ-event (the gospel) as the basis of our salvation and, in turn, the objective importance of Old Testament history. This is, of course, a very different thing from the modern approach of seeing the Old Testament as part of the historical development of man’s religious ideas, or as merely a background history to the New Testament age. Basically, the Old Testament is not the history of man’s developing thoughts about God, but the whole Bible presents itself as the unfolding process of God’s dealings with man and of his own self-disclosure to man.

Is the Old Testament For All Christians?

The most compelling reason for Christians to read and study the Old Testament lies in the New Testament. The New Testament witnesses to the fact that Jesus of Nazareth is the One in whom and through whom all the promises of God find their fulfilment. These promises are only to be understood from the Old Testament; the fulfilment of the promises can be understood only in the context of the promises themselves. The New Testament presupposes a knowledge of the Old Testament. Everything that is a concern to the New Testament writers is part of the one redemptive history to which the Old Testament witnesses. The New Testament writers cannot separate the person and work of Christ, nor the life of the Christian community, from this sacred history which has its beginnings in the Old Testament.

It is, of course, of great significance that the New Testament writers constantly quote or allude to the Old Testament. One estimate is that there are at least 1600 direct quotations of the Old Testament in the New, to which may be added several thousand more New Testament passages that clearly allude to or reflect Old Testament verses.4 Of course not all these citations show direct continuity of thought with the Old Testament, and some even show a contrast between Old and New Testaments. But the over-all effect is inescapable – the message of the New Testament has its foundations in the Old Testament.

Contrary to what is sometimes suggested, the New Testament writers were not in the habit of quoting texts without reference to their context. In fact a quotation is sometimes intended to prompt the recall of an entire passage of Old Testament scripture. For example, Paul’s quotation in I Corinthians 10: 7 of part of Exodus 32:6 refers to the festivities of the Israelites. The intention is to bring to mind the whole narrative of Israel’s idolatry and the golden calf.

A person may become a Christian without much knowledge of the Old Testament. Conversion does, however, require a basic understanding of Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord. The Christian cannot be committed to Christ without being committed to his teaching. It follows that Christ’s attitude to the Old Testament will begin to convey itself to the Christian who is carefully studying the New Testament. The more we study the New Testament the more apparent becomes the conviction shared by Jesus, the apostles and the New Testament writers in general: namely the Old Testament is Scripture and Scripture points to Christ. The manner in which the Old Testament testifies to Christ is a question that has to be resolved on the basis of the New Testament, since it is the New Testament which provides the Christian with an authoritative interpretation of the Old.

The effect of this is twofold. As Christians we will always be looking at the Old Testament from the standpoint of the New Testament – from the framework of the gospel which is the goal of the Old Testament. But since the New Testament continually presupposes the Old Testament as a unity we, who are not acquainted with the Old Testament in the way the first Christians were, will be driven back to study the Old Testament on its own terms. To understand the whole living process of redemptive history in the Old Testament we must recognize two basic truths. The first is that this salvation history is a process. The second is that this process of redemptive history finds its goal, its focus and fulfilment in the person and work of Christ. This is the principle underlying this book.

Failure to grasp this truth – largely because the proper study of the Old Testament has been neglected, has aided and abetted one of the most unfortunate reversals in evangelical theology. The core of the gospel, the historical facts of what God did in Christ, is often down-graded today in favour of a more mystical emphasis on the private spiritual experience of the individual. Whereas faith in the gospel is essentially acceptance of, and commitment to, the declaration that God acted in Christ some two thousand years ago on our behalf, saving faith is often portrayed nowadays more as trust in what God is doing in us now. Biblical ideas such as ‘the forgiveness of sins’ or ‘salvation’ are interpreted as primarily describing a Christian’s personal experience. But when we allow the whole Bible – Old and New Testaments – to speak to us, we find that those subjective aspects of the Christian life which are undoubtedly important – the new birth, faith and sanctification – are the fruits of the gospel. This gospel, while still relating to individual people at their point of need, is rooted and grounded in the history of redemption. It is the good news about Jesus, before it can become good news for sinful men and women. Indeed, it is only as the objective (redemptive-historical) facts are grasped that the subjective experience of the individual Christian can be understood.

At this point, some readers may be thinking that we have strayed from our original aim by discussing the history of biblical interpretation. I hope that a few technical points will not deter them, for it is my solid conviction that all Christians need to develop a biblical way of understanding the Bible and of using it. It is not only possible but even necessary for all Christians, including children, to gain a total perspective on the whole Bible so that the really important relationships between its parts begin to appear.

1 See Beryl Smalley, The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages (University of Notre Dame Press, 1964), Chapter 5. Stephen Langton (died 1228) applied the allegorical and spiritual interpretation with vigour. For example II Kings 1:2 – Ahaziah fell through the lattice in his upper chamber in Samaria and lay sick – signifies a church prelate who enters hastily into the perplexities of his pastoral charge and falls into sin. Boaz in the Book of Ruth is made to represent God. When he enquires of the reapers ‘Whose maid is this?’ (Ruth 2:5) he is enquiring of the doctors of theology concerning the status of the preacher who gathers sentences of Scripture for his preaching. A modern example of allegorical exposition with very great similarities to the mediaeval method of interpretation is to be found in W. Ian Thomas, If I Perish I Perish (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1967). The author deals with the Book of Esther and makes Ahasuerus represent the soul of man, Haman the sinful flesh, Mordecai the Holy Spirit, and Esther the human spirit.

2 See J.S. Preus, From Shadow to Promise (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1969).

3 A useful introduction to the subject of interpretation is found in R.M. Grant, A Short History of the Interpretation of the Bible (New York: Macmillan, 1948).

4 Henry M. Shires, Finding the Old Testament in the New (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1974), p. 15.

From Gospel in Kingdom in The Goldsworthy Trilogy by Graeme Goldsworthy