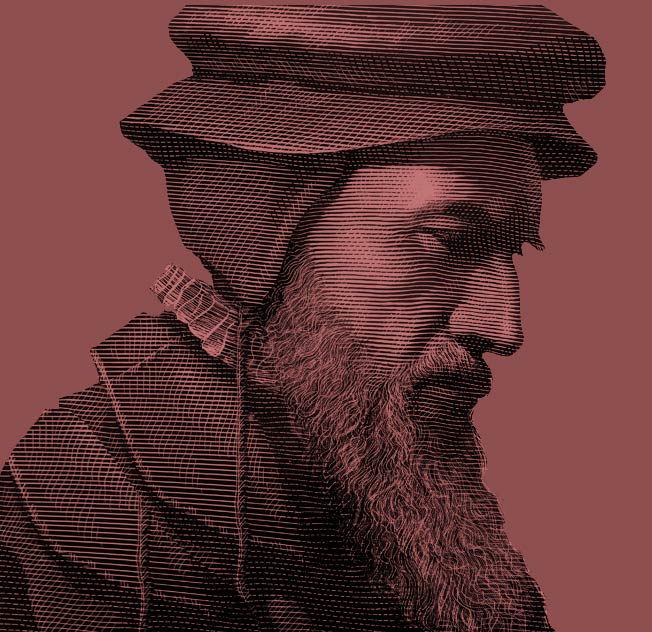

by John Calvin

by John Calvin

IT IS NOT A CASE OF THE BELIEVER'S "CO-OPERATION" WITH GRACE; THE WILL IS FIRST ACTUATED THROUGH GRACE

But perhaps some will concede that the will is turned away from the good by its own nature and is converted by the Lord's power alone, yet in such a way that, having been prepared, it then has its own part in the action. As Augustine teaches, grace precedes every good work; while will does not go before as its leader but follows after as its attendant. This statement, which the holy man made with no evil intention, has by Lombard been preposterously twisted to that way of thinking. But I contend that in the words of the prophet that I have cited, as well as in other passages, two things are clearly signified: (1) the Lord corrects our evil will, or rather extinguishes it; (2) he substitutes for it a good one from himself.

In so far as it is anticipated by grace, to that degree I concede that you may call your will an "attendant." But because the will reformed is the Lord's work, it is wrongly attributed to man that he obeys prevenient grace with his will as attendant. Therefore Chrysostom erroneously wrote: "Neither grace without will nor will without grace can do anything." As if grace did not also actuate the will itself, as we have just seen from Paul [cf. Philippians 2:13]! Nor was it Augustine's intent, in calling the human will the attendant of grace, to assign to the will in good works a function second to that of grace. His only purpose was, rather, to refute that very evil doctrine of Pelagius which lodged the first cause of salvation in man's merit.

Enough for the argument at hand, Augustine contends, was the fact that grace is prior to all merit. In the meantime he passes over the other question, that of the perpetual effect of grace, which he nevertheless brilliantly discusses elsewhere. For while Augustine on several occasions says that the Lord anticipates an unwilling man that he may will, and follows a willing man that he may not will in vain, yet he makes God himself wholly the Author of good works. However, his statements on this matter are clear enough not to require a long review. "Men labor," he says, "to find in our will something that is our own and not of God; and I know not how it can be found." Moreover, in Against Pelagius and Caelestius, Book I, he thus interprets Christ's saying "Every one who has heard from my Father comes to me" [John 6:45 p.]: "Man's choice is so assisted that it not only knows what it ought to do, but also does because it has known. And thus when God teaches not through the letter of the law but through the grace of the Spirit, He so teaches that whatever anyone has learned he not only sees by knowing, but also seeks by willing, and achieves by doing."

SCRIPTURE IMPUTES TO GOD ALL THAT IS FOR OUR BENEFIT

Well, then, since we are now at the principal point, let us undertake to summarize the matter for our readers by but a few, and very clear, testimonies of Scripture. Then, lest anyone accuse us of distorting Scripture, let us show that the truth, which we assert has been drawn from Scripture, lacks not the attestation of this holy man - I mean Augustine. I do not account it necessary to recount item by item what can be adduced from Scripture in support of our opinion, but only from very select passages to pave the way to understanding all the rest, which we read here and there. On the other hand, it will not be untimely for me to make plain that I pretty much agree with that man whom the godly by common consent justly invest with the greatest authority.

Surely there is ready and sufficient reason to believe that good takes its origin from God alone. And only in the elect does one find a will inclined to good. Yet we must seek the cause of election outside men. It follows, thence, that man has a right will not from himself, but that it flows from the same good pleasure by which we were chosen before the creation of the world [Ephesians 1:4]. Further, there is another similar reason: for since willing and doing well take their origin from faith, we ought to see what is the source of faith itself.

But since the whole of Scripture proclaims that faith is a free gift of God, it follows that when we, who are by nature inclined to evil with our whole heart, begin to will good, we do so out of mere grace. Therefore, the Lord when he lays down these two principles in the conversion of his people - that he will take from them their "heart of stone" and give them "a heart of flesh" [Ezekiel 36:26] - openly testifies that what is of ourselves ought to be blotted out to convert us to righteousness; but that whatever takes its place is from him. And he does not declare this in one place only, for he says in Jeremiah: "I will give them one heart and one way, that they may fear me all their days" [Jeremiah 32:39]. A little later: "I will put the fear of my name in their heart, that they may not turn from me" [Jeremiah 32:40]. Again, in Ezekiel: "I will give them one heart and will give a new spirit in their inward parts. I will take the stony heart out of their flesh and give them a heart of flesh" [Ezekiel 11:19]. He testifies that our conversion is the creation of a new spirit and a new heart. What other fact could more clearly claim for him, and take away from us, every vestige of good and right in our will? For it always follows that nothing good can arise out of our will until it has been reformed; and after its reformation, in so far as it is good, it is so from God, not from ourselves.

THE PRAYERS IN SCRIPTURE ESPECIALLY SHOW HOW THE BEGINNING, CONTINUATION, AND END OF OUR BLESSEDNESS COME FROM GOD ALONE

So, also, do we read the prayers composed by holy men. "May the Lord incline our heart to him," said Solomon, "that we may keep his commandments." [1 Kings 8:58 p.] He shows the stubbornness of our hearts: by nature they glory in rebelling against God's law, unless they be bent. The same view is also held in The Psalms: "Incline my heart to thy testimonies [Psalm 119:36]. We ought always to note the antithesis between the perverse motion of the heart, by which it is drawn away to obstinate disobedience, and this correction, by which it is compelled to obedience. When David feels himself bereft, for a time, of directing grace, and prays God to "create in" him "a clean heart," "to renew a right Spirit in his inward parts" [Psalm 51: 10; cf. Psalm 50:12, Vg.], does he not then recognize that all parts of his heart are crammed with uncleanness, and his spirit warped in depravity? Moreover, does he not, by calling the cleanness he implores "creation of God," attribute it once received wholly to God? If anyone objects that this very prayer is a sign of a godly and holy disposition, the refutation is ready: although David had in part already repented, yet he compared his previous condition with that sad ruin which he had experienced. Therefore, taking on the role of a man estranged from God, he justly prays that whatever God bestows on his elect in regeneration be given to himself. Therefore, he desired himself to be created anew, as if from the dead, that, freed from Satan's ownership, he may become an instrument of the Holy Spirit. Strange and monstrous indeed is the license of our pride! The Lord demands nothing stricter than for us to observe his Sabbath most scrupulously [Exodus 20:8 ff.; Deuteronomy 5:12 ff.], that is, by resting from our labors. Yet there is nothing that we are more unwilling to do than to bid farewell to our own labors and to give God's works their rightful place. If our unreason did not stand in the way, Christ has given a testimony of his benefits clear enough so that they cannot be spitefully suppressed. "I am," he says, "the vine, you the branches [John 15:5]; my Father is the cultivator [John 15:1]. Just as branches cannot bear fruit of themselves unless they abide in the vine, so can you not unless you abide in me [John 5:4]. For apart from me you can do nothing" [John 5:5].

If we no more bear fruit of ourselves than a branch buds out when it is plucked from the earth and deprived of moisture, we ought not to seek any further the potentiality of our nature for good. Nor is this conclusion doubtful: "Apart from me you can do nothing" [John 15;5]. He does not say that we are too weak to be sufficient unto ourselves, but in reducing us to nothing he excludes all estimation of even the slightest little ability. If grafted in Christ we bear fruit like a vine - which derives the energy for its growth from the moisture of the earth, from the dew of heaven, and from the quickening warmth of the sun - I see no share in good works remaining to us if we keep unimpaired what is God's. In vain this silly subtlety is alleged: there is already sap enclosed in the branch, and the power of bearing fruit; and it does not take everything from the earth or from its primal root, because it furnishes something of its own. Now Christ simply means that we are dry and worthless wood when we are separated from him, for apart from him we have no ability to do good, as elsewhere he also says: "Every tree which my Father has not planted will be uprooted" [Matthew 15:13, cf. Vg.]. For this reason, in the passage already cited the apostle ascribes the sum total to him. "It is God," says he, "who is at work in you, both to will and to work." [Philippians 2:13.]

The first part of a good work is will; the other, a strong effort to accomplish it; the author of both is God. Therefore we are robbing the Lord if we claim for ourselves anything either in will or in accomplishment. If God were said to help our weak will, then something would be left to us. But when it is said that he makes the will, whatever of good is in it is now placed outside us. But since even a good will is weighed down by the burden of our flesh so that it cannot rise up, he added that to surmount the difficulties of that struggle we are provided with constancy of effort sufficient to achieve this. Indeed, what he teaches in another passage could not otherwise be true: "It is God alone who works all things in all" [1 Corinthians 12:6]. In this statement, as we have previously noted, the whole course of the spiritual life is comprehended. So, too, David, after he has prayed the ways of God be made known to him so that he may walk in his truth, immediately adds, "Unite my heart to fear thy name" [Psalm 86:11; cf. Psalm 119:33]. By these words he means that even well-disposed persons have been subject to so many distractions that they readily vanish or fall away unless they are strengthened to persevere. In this way elsewhere, after he has prayed that his steps be directed to keep God's word, he begs also to be given the strength to fight: "Let no iniquity," he says, "get dominion over me" 119:133]. Therefore the Lord in this way both begins and completes the good work in us. It is the Lord's doing that the will conceives the love of what is right, is zealously inclined toward it, is aroused and moved to pursue it. Then it is the Lord's doing that the choice, zeal, and effort do not falter, but proceed even to accomplishment; lastly, that man goes forward in these things with constancy, and perseveres to the very end.

GOD'S ACTIVITY DOES NOT PRODUCE A POSSIBILITY THAT WE CAN EXHAUST, BUT AN ACTUALITY TO WHICH WE CANNOT ADD

He does not move the will in such a manner as has been taught and believed for many ages - that it is afterward in our choice either to obey or resist the motion - but by disposing it efficaciously. Therefore one must deny that oft-repeated statement of Chrysostom: "Whom he draws he draws willing." By this he signifies that the Lord is only extending his hand to await whether we will be pleased to receive his aid. We admit that man's condition while he still remained upright was such that he could incline to either side. But inasmuch as he has made clear by his example how miserable free will is unless God both wills and is able to work in us, what will happen to us if he imparts his grace to us in this small measure? But we ourselves obscure it and weaken it by our unthankfulness. For the apostle does not teach that the grace of a good will is bestowed upon us if we accept it, but that He wills to work in us. This means nothing else than that the Lord by his Spirit directs, bends, and governs, our heart and reigns in it as in his own possession, indeed, he does not promise through Ezekiel that he will give a new Spirit to his elect only in order that they may be able to walk according to his precepts, but also that they may actually so walk [Ezekiel 11:19-20; 36:27].

Now can Christ's saying ("Every one who has heard... from the Father comes to me" [John 6:45, cf. Vg.]) be understood in any other way than that the grace of God is efficacious of itself. This Augustine also maintains. The Lord does not indiscriminately deem everyone worthy of this grace, as that common saying of Ockham (unless I am mistaken) boasts: grace is denied to no one who does what is in him. Men indeed ought to be taught that God's loving-kindness is set forth to all who seek it, without exception. But since it is those on whom heavenly grace has breathed who at length begin to seek after it, they should not claim for themselves the slightest part of his praise. It is obviously the privilege of the elect that, regenerated through the Spirit of God, they are moved and governed by his leading. For this reason, Augustine justly derides those who claim for themselves any part of the act of willing, just as he reprehends others who think that what is the special testimony of free election is indiscriminately given to all. "Nature," he says, "is common to all, not grace." The view that what God bestows upon whomever he wills is generally extended to all, Augustine calls a brittle glasslike subtlety of wit, which glitters with mere vanity. Elsewhere he says: "How have you come? By believing. Fear lest while you are claiming for yourself that you have found the just way, you perish from the just way. I have come, you say, of my own free choice; I have come of my own will. Why are you puffed up? Do you wish to know that this also has been given you? Hear Him calling, 'No one comes to me unless my Father draws him' [John 6:44 p.]." And one may incontrovertibly conclude from John's words that the hearts of the pious are so effectively governed by God that they follow Him with unwavering intention. "No one begotten of God can sin," he says, "for God's seed abides in him." [1 John 3:9.] For the intermediate movement the Sophists dream up, which men are free either to accept or refuse, we see obviously excluded when it is asserted that constancy is efficacious for perseverance.

PERSEVERANCE IS EXCLUSIVELY GOD'S WORK; IT IS NEITHER A REWARD NOR A COMPLEMENT OF OUR INDIVIDUAL ACT

Perseverance would, without any doubt, be accounted God's free gift if a most wicked error did not prevail that it is distributed according to men's merit, in so far as each man shows himself receptive to the first grace. But since this error arose from the fact that men thought it in their power to spurn or to accept the proffered grace of God, when the latter opinion is swept away the former idea also falls of itself. However, there is here a twofold error. For besides teaching that our gratefulness for the first grace and our lawful use of it are rewarded by subsequent gifts, they add also that grace does not work in us by itself, but is only a co-worker with us.

As for the first point: we ought to believe that - while the Lord enriches his servants daily and heaps new gifts of his grace upon them - because he holds pleasing and acceptable the work that he has begun in them, he finds in them something he may follow up by greater graces. This is the meaning of the statement, "To him who has shall be given" [Matthew 25:29; Luke 19:26]. Likewise: "Well done, good servant; you have been faithful in a few matters, I will set you over much" [Matthew 25:21,23; Luke 19:17; all Vg., conflated]. But here we ought to guard against two things: (1) not to say that lawful use of the first grace is rewarded by later graces, as if man by his own effort rendered God's grace effective; or (2) so to think of the reward as to cease to consider it of God's free grace.

I grant that believers are to expect this blessing of God: that the better use they have made of the prior graces, the more may the following graces be thereafter increased. But I say this use is also from the Lord and this reward arises from his free benevolence. And they perversely as well as infelicitously utilize that worn distinction between operating and co-operating grace. Augustine indeed uses it, but moderates it with a suitable definition: God by co-operating perfects that which by operating he has begun. It is the same grace but with its name changed to fit the different mode of its effect. Hence it follows that he is not dividing it between God and us as if from the individual movement of each a mutual convergence occurred, but he is rather making note of the multiplying of grace. What he says elsewhere bears on this: many gifts of God precede man's good will, which is itself among his gifts. From this it follows that the will is left nothing to claim for itself. This Paul has expressly declared. For after he had said, "It is God who works in us to will and to accomplish," he went on to say that he does both "for his good pleasure" [Philippians 2:13 p.]. By this expression he means that God's loving-kindness is freely given. To this, our adversaries usually say that after we have accepted the first grace, then our own efforts co-operate with subsequent grace. To this I reply: If they mean that after we have by the Lord's power once for all been brought to obey righteousness, we go forward by our own power and are inclined to follow the action of grace, I do not gainsay it. For it is very certain that where God's grace reigns, there is readiness to obey it. Yet whence does this readiness come? Does not the Spirit of God, everywhere self-consistent, nourish the very inclination to obedience that he first engendered, and strengthen its constancy to persevere? Yet if they mean that man has in himself the power to work in partnership with God's grace, they are most wretchedly deluding themselves.

MAN CANNOT ASCRIBE TO HIMSELF EVEN ONE SINGLE GOOD WORK APART FROM GOD'S GRACE

Through ignorance they falsely twist to this purport that saying of the apostle: "I labored more than they all - yet not I but the grace of God which was with me" [1 Corinthians 15:10]. Here is how they understand it: because it could have seemed a little too arrogant for Paul to say he preferred himself to all, he therefore corrected his statement by paying the credit to God's grace; yet he did this in such a way as to call himself a fellow laborer in grace. It is amazing that so many otherwise good men have stumbled on this straw. For the apostle does not write that the grace of the Lord labored with him to make him a partner in the labor. Rather, by this correction he transfers all credit for labor to grace alone. "It is not I," he says, "who labored, but the grace of God which was present with me." [1 Corinthians 15:10 p.] Now, the ambiguity of the expression deceived them, but more particularly the absurd Latin translation in which the force of the Greek article had been missed. For if you render it word for word, he does not say that grace was a fellow worker with him; but that the grace that was present with him was the cause of everything. Augustine teaches this clearly, though briefly, when he speaks as follows: "Man's good will precedes many of God's gifts, but not all. The very will that precedes is itself among these gifts. The reason then follows: for it was written, 'His mercy anticipates me' [Psalm 59:10; cf. Psalm 58:11 Vg.]. And 'His mercy will follow me' [Psalm 23:6]. Grace anticipates unwilling man that he may will; it follows him willing that he may not will in vain." Bernard agrees with Augustine when he makes the church speak thus: "Draw me, however unwilling, to make me willing; draw me, slow-footed, to make me run."

AUGUSTINE ALSO RECOGNIZES NO INDEPENDENT ACTIVITY OF THE HUMAN WILL

Now let us hear Augustine speaking in his own words, lest the Pelagians of our own age, that is, the Sophists of the Sorbonne, according to their custom, charge that all antiquity is against us. In this they are obviously imitating their father Pelagius, by whom Augustine himself was once drawn into the same arena. In his treatise On Rebuke and Grace to Valentinus, Augustine treats more fully what I shall refer to here briefly, yet in his own words. The grace of persisting in good would have been given to Adam if he had so willed. It is given to us in order that we may will, and by will may overcome concupiscence. Therefore, he had the ability if he had so willed, but he did not will that he should be able. To us it is given both to will and to be able. The original freedom was to be able not to sin; but ours is much greater, not to be able to sin. And that no one may think that he is speaking of a perfection to come after immortality, as Lombard falsely interprets it, Augustine shortly thereafter removes this doubt. He says: "Surely the will of the saints is so much aroused by the Holy Spirit that they are able because they so will, and that they will because God brings it about that they so will. Now suppose that in such great weakness in which, nevertheless, God's power must be made perfect to repress elation [2 Corinthians 12:9], their own will were left to them in order, with God's aid, to be able, if they will, and that God does not work in them that they will: amid so many temptations the will itself would then succumb through weakness, and for that reason they could not persevere. Therefore assistance is given to the weakness of the human will to move it unwaveringly and inseparably by divine grace, and hence, however great its weakness, not to let it fail." He then discusses more fully how our hearts of necessity respond to God as he works upon them. Indeed, he says that the Lord draws men by their own wills, wills that he himself has wrought. Now we have from Augustine's own lips the testimony that we especially wish to obtain: not only is grace offered by the Lord, which by anyone's free choice may be accepted or rejected; but it is this very grace which forms both choice and will in the heart, so that whatever good works then follow are the fruit and effect of grace; and it has no other will obeying it except the will that it has made. There are also Augustine's words from another place: "Grace alone brings about every good work in us."

AUGUSTINE DOES NOT ELIMINATE MAN'S WILL, BUT MAKES IT WHOLLY DEPENDENT UPON GRACE

Elsewhere he says that will is not taken away by grace, but is changed from evil into good, and helped when it is good. By this he means only that man is not borne along without any motion of the heart, as if by an outside force; rather, he is so affected within that he obeys from the heart. Augustine writes to Boniface that grace is specially and freely given to the elect in this manner: "We know that God's grace is not given to all men. To those to whom it is given it is given neither according to the merits of works, nor according to the merits of the will, but by free grace. To those to whom it is not given we know that it is because of God's righteous judgment that it is not given." And in the same epistle he strongly challenges the view that subsequent grace is given for men's merits because by not rejecting the first grace they render themselves worthy. For he would have Pelagius admit that grace is necessary for our every action and is not in payment for our works, in order that it may truly be grace. But the matter cannot be summed up in briefer form than in the eighth chapter of the book On Rebuke and Grace to Valentinus. There Augustine first teaches: the human will does not obtain grace by freedom, but obtains freedom by grace; when the feeling of delight has been imparted through.67 the same grace, the human will is formed to endure; it is strengthened with unconquerable fortitude; controlled by grace, it never will perish, but, if grace forsake it, it will straightway fall; by the Lord's free mercy it is converted to good, and once converted it perseveres in good; the direction of the human will toward good, and after direction its continuation in good, depend solely upon God's will, not upon any merit of man. Thus there is left to man such free will, if we please so to call it, as he elsewhere describes: that except through grace the will can neither be converted to God nor abide in God; and whatever it can do it is able to do only through grace.

----

Excerpt from Institutes of the Christian Religion by John Calvin